Can democracy work in Africa?

Africa - Revista 06.02.2022 Alberto Salza Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgOnly seven of the 37 countries that proclaimed their independence in the late 1960s had institutional arrangements we could consider democratic. Most of them were former British colonies with parliamentary systems similar to that of their former motherland. In nine other countries (including Congo-Kinshasa, Ghana and Kenya), the first post-independence leaders had come to power in multi-party elections, albeit in contexts lacking the minimum standards for a democracy. Less than half of sub-Saharan African leaders at the time of independence had some form of electoral legitimacy. Today, 43% of African states are considered democratic; only four countries - Eritrea, Eswatini, Somalia and South Sudan - do not hold periodic elections. Between 1960 and 1990, leadership changes through electoral process were extremely rare: six cases of electoral changes and three cases of alternation in government. Since the 1990s, most political regimes have opened up to a multi-party system. Both the number of electoral changes and of alternations in power has grown with the “record” of 21 alternations in the current decade. This opening has had an impact on the political dynamics and on the development levels of the sub-Saharan countries. A study on data from the Africa Leadership Change Project, shows that regimes with the highest number of multi-party elections and government alternations have higher rate of economic growth, better welfare conditions, stronger state administrations, and lower levels of corruption than the regimes less open to political change (See, Africa: how much democracy south of the Sahara? by Alessandro Pellegata - Ispi). An anthropologist therefore wonders about the impact and effectiveness of the "government of the people" on the continent. Did the "democracy" made up of elections, parties, and parliaments, imported - sometimes imposed by the West -, bear the hoped-for results?

Democracy is a form of language: if you don't know it, it requires translation, otherwise you don't understand anything and end up like that sergeant of the US special forces who in Ogaden, on the border between Ethiopia and Somalia, told me: "I thought being here was to export democracy, not to be part of it.” He was right, especially as regards democracy in Africa: the proof of democracy is not if the people vote, whatever it takes, but if the people govern.

It is not that in Athens...

As a demonstration of how important the language of democracy is, see how the word "government" is ambiguous: it derives from the same Latin root of "rudder". Whoever rules, holds the bar. Who gives him the route to follow? Who is in charge of the ship? Would you trust someone telling you let me steer? Do you know where he is going? The Luluwa of the Congo and the Mossi of Burkina Faso, demonstrating how much there is a common basis of thought in Africa (often denied by relativism pundits), say, "Being a boss it takes men, men need a leader". Democracy is a form of power, not a pious wish to share, and therefore does not escape its law.

Until colonization, the forms of power in sub-Saharan Africa historically and geographically followed the trend of population density. The band of Bushmen who welcomed me in the Kalahari Desert lived in a territory with less than one inhabitant per square kilometer; the hunter-gatherer community was headless; families made decisions and, if someone did not agree, it went elsewhere.

The spread of agriculture, increased with iron technology by the Bantu-speaking populations starting from Cameroon, was initially based on small densely populated nuclei in the midst of deforested forests and savannahs, led by an authoritative person. Later, the system of power extended into a network of chefferies, centers whose density was equal to territorial extension. These domains were characterized by inequality, with the central power more or less distributed among the higher social classes. Nothing like democracy; however, it should be remembered that Athenian democracy involved only 10% of the population: the male landlords.

The authority of the elderly

In favorable territories such as the Great Lakes region, African history sees the subsequent formation of kingdoms and empires with the increase in population and the merger of domains. The words "kingdom" and "empire" - assonances of the Indo-European equivalent -, were recognizable by their monocratic guidance, even if compensated by regulatory mechanisms such as the councils of the elders (etymology of "senate") or the intricate regulations that interfered with the patrilineal lineage. For example, in southern Africa, the maternal uncle exercised great influence over the king and his decisions. In addition, the king was a kind of CEO who redistributed wealth as dividends to subjects (shareholders), proving that in Africa what matters is the community, not the individual.

The shepherds make their own story. They had to (and still must) move in search of unpredictable and low-yield resources (grass and water). The resulting wide-ranging nomadism cannot support a centralized form of power: decisions must be taken on the spot and when the atmospheric and plant variability dictate it. As a result, the pastors endowed themselves with apparently democratic forms of "government". In reality, it was and it is a gerontocracy where the "it has always been done this way" wins and innovation has no way. Here what governs is the authority (better, authoritativeness) and not the power: the elderly use the curse as the only legal institution to force young people to follow their decisions.

The power of the words

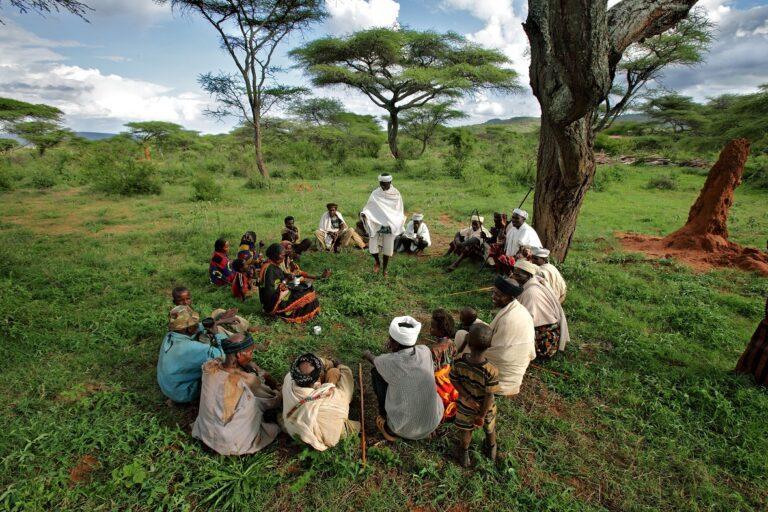

I have participated in hundreds of assemblies among the pastors of Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia. It is a demented experience. Anyone, among adult men, can speak up and plead for any cause. Generally, it is a matter of serious things, so everyone must contribute to the debate with the appropriate rhetoric. Sometimes it is about a hundred elderly people, very verbose due to a cultural imperative. The problem, democratically speaking, is that there is no vote: decisions are not taken by majority but by unanimity. Hours and hours are spent crouched under an acacia tree (if any) trying to convince the refractory. In practice, those with rhetorical and command skills (demonstrated in raids) are recognized as temporary leaders to be consulted at critical moments. The ballots are not foreseen: in the end, they convince you out of sheer exhaustion.

In 2005-06, I went to Ogaden for an impossible mission: to organize a human rights association among Somali pastors, people who love Kalashnikovs, trust in jihad, infibulate girls and believe that women have a fundamental right: to obey their husbands (the only answer I was given on the spot). Yet, by reading the Constitution (what else could I do?) I was able to enter the local power management system. It is a form of eu-cracy ("good governance") where the quantity (votes) does not prevail, but the quality of the people. The quality of persons manifests itself above all through words: the Somali pastors told me to be guided by poetry, not by necessity. Would you take the floor? Right! Democracy, like any other power, does not come as a gift: you have to take it. To close the circle, I learned from the Somalis and their practice that, to speak, one must "keep the stick straight": this is the origin of the term "right".

The science of the worst

Upon these community-based institutions came colonization (with subjects of inferior race), followed by democratization (individuals all equal), without solution of continuity, without forms of learning, without cultural changes, without protection of community values. It was the disaster of democracy imposed as a system and not suggested as a process.

The African rulers, then, do their best to muddy the waters. According to Edem Kodjo, former Togolese premier until 2006, "the African spirit is characterized by a conception of existence dominated by the idea of a creative power, transcendent and contrary to social upheaval. This reduces the spirit of initiative towards everything that is unknown." Thus, the permanence of the democratic tyrants of Africa would be explained divinely. Alternatively, there would be the growing ideology that "democracy is non-African". China’s economic growth, in the absence of rights and real democracy, is seen in Africa as a culturally and economically viable model, so: "First development, then democracy". As a Kenyan anthropologist explains: “We apply the kakonomia, the science of the worst (from the Greek kakós, bad). It is a theory of human motivation trying to explain why it is sometimes rational to prefer the worst to the best."

So, it doesn't work

The superimposition of colonial-inspired democracy on local power creates the basis of the continuous rebound of responsibility and accountability: the premise is that in the West we have come to consider democracy as a mere fact of more or less successful elections. In Africa the “one man one vote” mechanism does not work, as society reasons and operates on a community basis. Among the Mossi, I found myself dealing more often with the nema (the traditional king) than with the government prefect.

There have been many attempts to form a hybrid governance, from the British colonialists' indirect rule for basic justice, to today's way of Somaliland where senior councils sit alongside the central government, while businessmen provide roads and security (if they do). At that point, however, you never know who should manage the every-day power and account for it to the population. African-style democracy, in addition to producing tyrants for life and misery, has largely created the conditions that have opened up space for the fundamentalists of Boko Haram ("no books"), or al-Shabaab ("the young people", in opposition to the vaunted "elderly"). The pulverization of traditional power has not meant democracy in Africa: it has devastated the connective tissue of communities.

See La democrazia funziona in Africa?

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment