The sinister side of African Aid

27.04.2014 Ellena Savage - Eureka Street Translated by: Jpic-jp.org People don't ignore starving people, so why should we ignore cold people? Frostbite kills people too. Pop singers join in an anthem to encourage Africans to donate heaters to needy Norwegians.

A few years ago, my brother and I took a trip through western Sumatra. It was my first time in a developing country, and the island we spent most of our time had been devastated by an earthquake a few years before.

Like many places that have been traumatized by disaster, corruption and poverty, it was ripe with contradictions: happy, clever kids, wild chooks, a joyful church scene, but also the desperate hustle for paid work in a cash economy, and for the basics like sanitation and protection against disease.

On one ride through the rice paddies, we drove past a farmhouse where barefoot children spilled out of the doorway and onto the yard. As they called out Mister! Mister! and I waved at them, I had a flashback of an image I had seen as a very young child.

When I was in primary school, a person from an aid agency came to our assembly to let us know that children like us overseas were dying, but that we could help them if we wanted to.

I took home some literature, presumably designed to collect donations from people who actually had the money, the parents. But the picture on the pamphlet disturbed me: a small child, about my own age, sitting on the stoop of a simple wooden house with a dirt floor, beside an infant.

The kids weren't injured or obviously starving, but they looked upset, and their sad story was printed next to them. I felt devastated: I cried at how hopeless their lives were, and how useless I was at saving them.

This was the point: to make Australian kids aware of their economic privilege and of the existence of aid programs. But I wonder if the influence of such material was more sinister, if it made us believe in the weakness of others and in our relative strength and moral purpose.

In Sumatra, it could have been these same kids: the simple house, the parents out working, and the material indications of poverty. Yet they were jubilant children, playing and posturing like kids do. Although some people in Sumatra benefit from various kinds of aid, they do not spend their lives staring gloomily down the lens of western sympathy. They have lives, too.

An online campaign, which is ruthless against the moral vanity of aid culture, directly addresses these issues of representation. Radi-Aid is an African aid drive to save Norway from its bitter plight.

“People don't ignore starving people, so why should we ignore cold people? Frostbite kills people too”, says the introducer. Pop singers join in an anthem to encourage the donation of heaters to needy Norwegians.

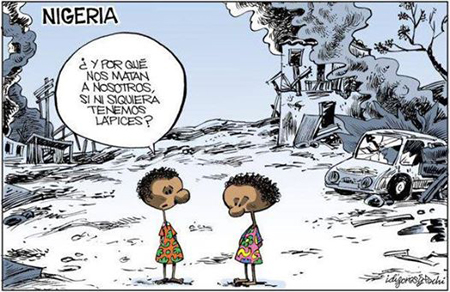

The campaign, which is such seamless satire that it takes a few moments to realize what is going on, is aimed at challenging patronizing representations of people in developing economies. Its website says, 'If we say Africa, what do you think about? Hunger, poverty, crime or AIDS? No wonder, because in fundraising campaigns and media that's mainly what you hear about.'

It brings to mind a well-known article from a 2005 edition of Granta, “How to Write about Africa”, by Binyavanga Wainaina. He writes, “Never have a picture of a well-adjusted African on the cover of your book, or in it, unless that African has won the Nobel Prize. An AK-47, prominent ribs, naked breasts: use these. If you must include an African, make sure you get one in Masai or Zulu or Dogon dress.”

Two-dimensional characterizations of Africa -which is so homogenously represented it seems as though it could be a country, and not the second largest and second most-populous continent made up of 54 sovereign states- make us ask how useful aid can be if it humiliates people in the long run. These representations are grounded in old colonial power relationships.

China, which is becoming increasingly dependent on African resources, has a mandate of giving fuller, more positive representations of African populations. Sure, it does so in pursuit of mutually beneficial business relationships. But at least this contributes to humane -rather than exploitative- business dealings.

It is also worth considering that while mainstream aid culture depends on an idea of passive suffering, our consumption habits necessitate poverty. The global distribution of labor means that someone else's material poverty benefits our material wealth.

Caught somewhere here is the need for human suffering to be documented, and for the stories of those in need to be heard.

It is grossly unfair that the world's aid efforts couldn't prevent a climate disaster from becoming a human disaster. So how do we try to understand these stories without characterizing them as victim narratives? Only with humor and respect, and when we can laugh at one another's prejudices. We all have them.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment