A new birth of the Catholic Church?

Catholic Herald 02.11.2017 Philip Jenkins Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThis article first appeared in the November 3 2017 issue of the Catholic Herald with this title: The Catholic world is about to be turned upside down. You are invited to go there, here we read it with the Christmas spirit full of hope. Just think: in just over 30 years time, one in four of the world’s Catholics are expected to live in Africa. By 2050, the leading Catholic nations will be in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Will this change everything?

The Catholic Church worldwide is passing through an era of historical transformation, a decisive shift in numbers towards the Global South – to Asia, Africa and Latin America. Many are aware of this trend as an abstract fact, but we are scarcely coming to terms with the implications for Church life, for the composition of Church leadership, and for its future policies. A southward-looking Church may be a vibrant and flourishing body, but it might pose some challenges for Catholics of the older Euro-American world.

The fact of that geographical shift is clear enough. A century ago, the European continent accounted for almost two thirds of the world’s Catholics. By 2050, that proportion will fall to perhaps a sixth. In that not-too-far future year, the Church’s greatest bastions will be in Latin America (perhaps 40 per cent), in Africa (25 per cent) and Asia (12 per cent).

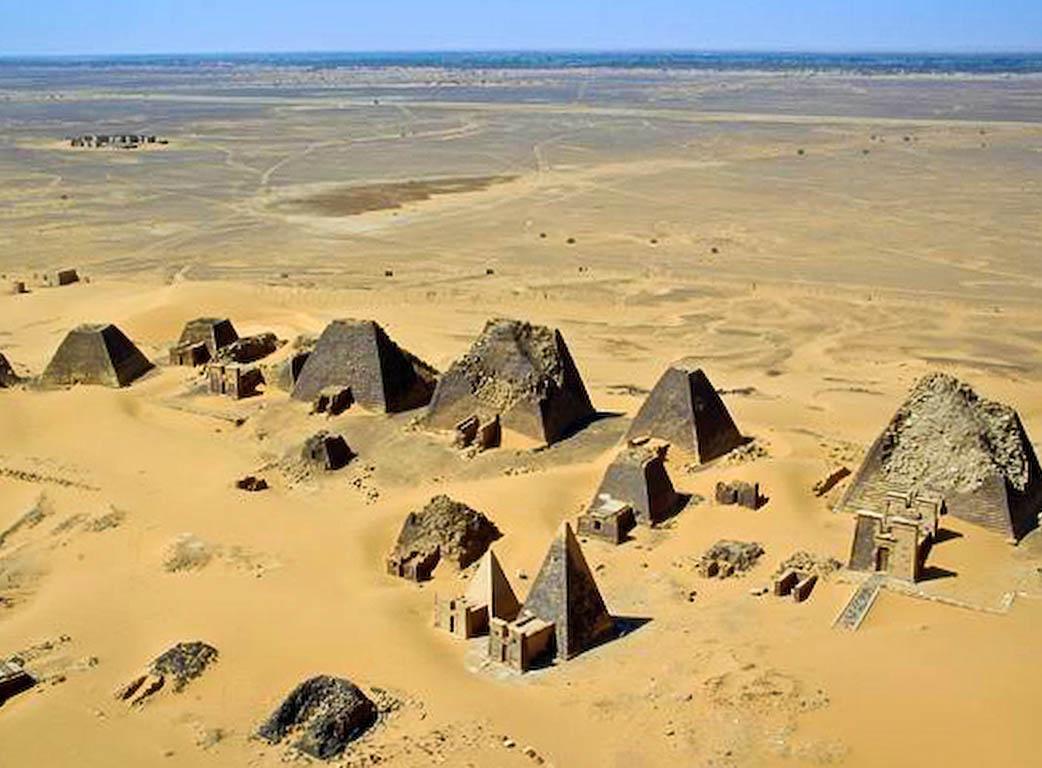

Actually, those numbers understate the southern predominance, because a sizeable number of Catholics living in Europe or North America will themselves be of migrant stock – Nigerians or Congolese in Europe, Mexicans in the United States. A Church born long ago on the soil of Asia and Africa is returning home.

Looking at a near-future list of the world’s largest Catholic nations reinforces that point about the relative decline of the Euro-American presence in the Church. In 1900, the three nations with the largest Catholic populations were France, Italy and Germany. By 2050, the leading countries will be Brazil, Mexico and the Philippines. France and Italy will comprise the only European entrants among the top 10 Catholic populations, which otherwise will include three African nations (Nigeria, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo), and the United States. With around a hundred million Catholics, the Democratic Republic of the Congo will enjoy rough parity with the United States and the Philippines. Those specific numbers are projections, and of course they may over- or under-estimate particular regions. But the general directions of change are not in doubt. The Catholic future lies in the South.

But what does that means for the Church’s leadership, for the composition of the College of Cardinals and for the papacy itself? Nobody advocates that the cardinals should be chosen on the basis of some kind of strict proportional representation, dependent on the findings of each new global census. Nor do cardinals represent constituencies. But the Church has long acknowledged that cardinals do play some kind of representative role, and of course they enjoy unique importance when the time comes to choose a new pope.

Over the past century, the College of Cardinals has become steadily more diverse and more global. The Italian contingent in the college has dropped sharply, from more than 50 per cent in 1920 to 35 per cent at the time of Vatican II, and to around 20 per cent today. Since the 1980s, all three successive popes have conspicuously tried to increase the numbers from the Global South. Today, the college includes 120 cardinals of voting age, of whom 54 come from Europe and 34 from the Americas. Africa has 15 and Asia 14, and these figures mark impressive growth. But they still fall short of any kind of “proportional” number. If cardinals were chosen on the basis of population, then already Africa should have 20 cardinals, besides earmarking multiple new places for the coming years.

It may take decades for the corps of cardinals to represent the actual distribution of numbers in the larger Catholic world, but we are definitely moving in that direction. As an intellectual exercise, consider what that college might look like in 2050, say, and imagine what impact that composition might have on the Church’s decisions and policies on any number of issues. What would the Church look like with, say, 120 voting cardinals, of whom 50 were Latin American, 30 African and 15 Asian? Imagine that the Democratic Republic of the Congo alone supplied seven or eight cardinals, with a similar number from the Philippines, and with swelling cohorts from other southern nations.

Geography is not destiny, but it is only natural that prelates from one part of the world will tend to speak for the traditions with which they are most familiar, which might well differ considerably from other regions. We saw early signs of this when the family synod was held in Rome in 2015, when the Church’s (mainly European) liberals proposed adopting a more welcoming attitude to gay Catholics and possibly allowing divorced and remarried believers to receive Communion. Those proposals met fierce resistance from African prelates, and the ensuing conflicts between conservatives and reformists were tainted by mutual recriminations and historical prejudices. Africans accused Europeans of imperialist racial attitudes, while some Europeans implied African backwardness.

Obviously, this precedent does not suggest that different regions are rigidly set in their attitudes, and cultural differences may well diminish over time. Significantly, it has been European and North American prelates who have led recent conservative resistance to Pope Francis, while Africans have remained out of the limelight.

Even so, it may be quite some time before African and Asian churches abandon their very rigorous attitudes on matters of human sexuality, and future North-South conflicts are only to be expected. The chief difference from the present is that the southerners will enjoy ever-larger numbers. Divisions within the Catholic Church fall far short of the passions that have driven a North-South schism within the Anglican Communion, but that is a troubling precedent.

However much attention those morality debates will continue to receive, they are by no means the only areas in which a future Church will adapt itself to the demands and interests of the new Catholic South. Some years ago, John Allen speculated wisely on these coming trends in his book The Future Church, and those predictions seem all the more likely today.

In Europe and North America, climate change is an issue of real concern, but for many in the Global South, planetary warming is literally a matter of life and death, of national survival. If there is any truth whatever in projected warming trends, then their impact will be most devastating in the tropics, those regions between 22 degrees north and 22 degrees south of the equator – or to put it another way, in the regions of most intense Catholic growth and expansion. Climate change will hit hardest and most directly in the precise regions where the largest number of Catholics will be living, in countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and Brazil.

The consequences of climate change could be ruinous, in terms of the effect on food production, water supplies and obtaining the necessities of life, and it is all but certain that the effects could provoke wars, and also drive waves of refugees on a scale unprecedented in human history. Already, the Vatican has become a leading voice on climate change issues, but that role would only increase if the future were to be as calamitous as seems likely. It is inconceivable that a southern-dominated Church could fail to make climate issues a critical priority, demanding sweeping changes in the policies of secular states.

To take another issue, the Church has long been committed to promoting dialogue with other world faiths, in the process raising some delicate theological issues about the proper relationship between Christian revelation and the claims of other religions.

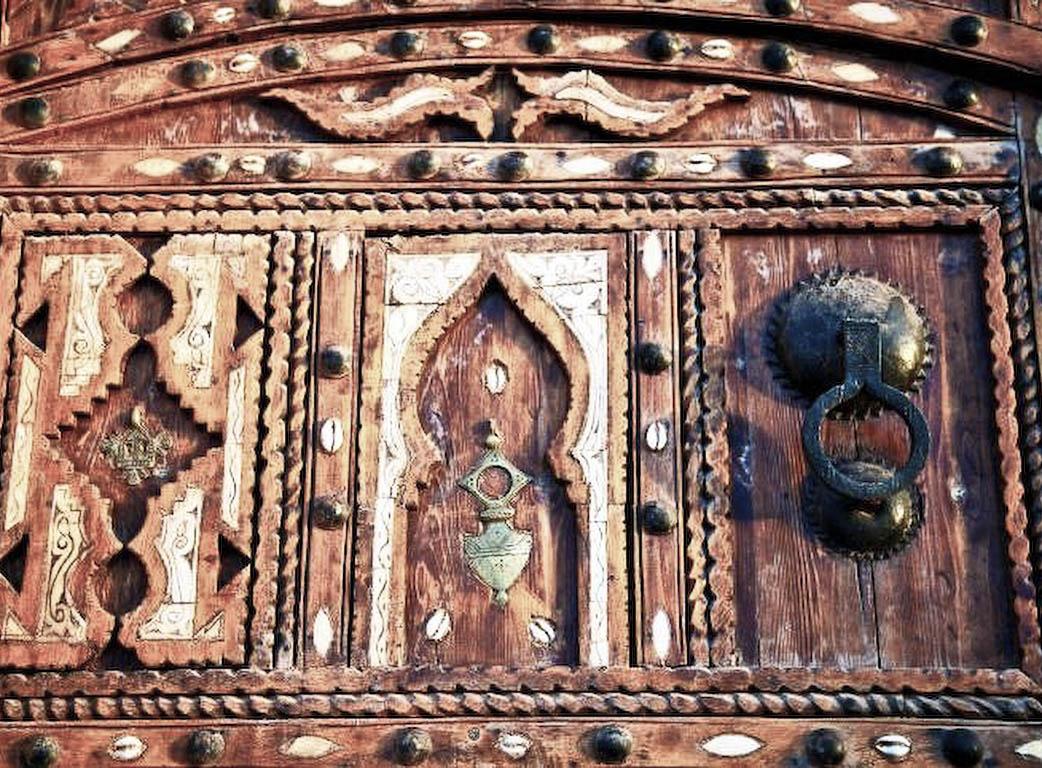

But that whole process of dialogue necessarily becomes quite different when the Church is dominated not by Europeans, but by Africans or Asians who have long experience interacting with Muslims, Buddhists or Hindus, and who must hammer out the details of coexistence on a daily basis. We could easily imagine a more southern-oriented Church speaking out even more forcefully, and more publicly, at times of confrontations between believers of different faiths, and in times of anti-Christian persecution.

We can only begin to imagine the ways in which that future Church might differ from our present assumptions. What we cannot doubt is that this Church will not remain blind to Global South problems and crises, nor that it will permit secular politicians and media to remain as silent as they have so often done in the past. Ideally, this coming Church would present a familiar Christian message, but in a truly global context.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment