A step forward... or a mockery?

Butembo 26.11.2024 Jpic-jp.org Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgCOP29 was held in Baku, Azerbaijan, from 11 to 22 November 2024, and was extended late into the night of Saturday 23 to Sunday 24 November, under the leadership of a presidency that was seen as lacklustre and in retreat. The parties to the Convention eventually adopted several texts, after long hours of bitter discussions and numerous postponements of meetings.

COP29 was expected to be a crucial event in the fight against climate change, bringing together representatives from nearly 200 countries to defend the planet. At a time when extreme weather events are raging everywhere, it set itself four ambitious objectives.

- Appropriate funding within a new framework, called a ‘collective quantified target’ (CQT), for developing countries to fight climate change. Contributions would include funding for adaptation, loss and damage from climate impacts. The 100 billion dollars per year established from 2020 in the COP15 agreements, a figure not reached until 2022, was to be raised to 2,400 billion per year as demanded by the countries concerned.

- The revision of the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), to reduce the emissions of each country in order to adapt to the effects of climate change. Current contributions put global warming at between 2.5°C and 2.9°C, beyond the 1.5°C limit required to control the impacts of climate change.

- Re-establish a ‘framework of enhanced transparency’ and mutual trust that will make it possible to assess the climate progress of each country and encourage the alignment of efforts by all to achieve climate objectives.

- Get the carbon markets up and running, by finalising the directives that make them operational. Progress has been made, but technical and political deadlocks are holding up these negotiations, which are crucial if companies are to reduce emissions.

With so much at stake at COP29, it is hardly surprising that the reactions at the conclusions were varied, mixed and even contradictory.

A deadlock

Up until the last moment, 335 organisations, signatories to a letter addressed to an alliance of 134 countries known as the G77 + China, were claiming that the text being prepared was ‘absolutely unacceptable’ because it would allow ‘developed countries to completely escape their obligations in terms of financing the fight against climate change’. ‘If nothing sufficiently strong is proposed at this COP, we invite you to leave the table to resume the fight another day, and we will fight with you’. ‘We insist: no agreement in Baku is better than a bad agreement, and this is a very, very bad agreement, because of the intransigence of the developed countries’, the letter insisted.

A step forward...

The last-minute agreement, adopted after long hours of bitter discussions and numerous postponements of sessions that satisfied no one, has the sole merit of having saved the image of COP29, because the hypocrisy of the Western countries was opposed by the intransigence of the underdeveloped countries, with numerous NGOs blowing on the fire.

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres spoke of an unambitious outcome, both in financial terms and in terms of the energy transition, when ‘the end of the fossil fuel era is an economic inevitability’. COP28 in Dubai called for ‘a just, orderly and equitable transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems’, a call not explicitly repeated in the text of COP29.

According to US President Joe Biden, the results of COP29 represent an important step forward, even though the US has never ratified the Paris agreements, despite its absence in Baku, and given that the climate-sceptic attitude of his successor, Donald Trump, is looming on the horizon.

UK Energy Secretary Ed Miliband hailed the agreement as a consistent step forward. ‘It's not everything we or others wanted, but it's a step forward for all of us’. The negotiations were difficult, but the Dubai consensus was successfully safeguarded, he stressed.

Wopke Hoekstra, the European Commissioner for Climate Change, who is now at the end of his mandate, spoke of the start of a new era, referring to the 300 billion dollars in climate funding for developing countries by 2035. ‘It's necessary, it's realistic and it's achievable’, he said. His enthusiasm was accompanied by disappointment: the agreement concerns only ‘the European countries, the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan and New Zealand’, when it was hoped that this list would be extended to include China, Singapore and the Gulf States. But for China, ‘that was out of the question’.

Disappointing, not up to the challenge, despite a number of advances, is the opinion of Agnès Pannier-Runacher, the French Minister for the Ecological Transition. She lamented that the text ‘was adopted in a climate of confusion and contested by several countries’, denouncing the fact that Baku was marked ‘by real disorganisation and a lack of leadership from the Presidency’.

Of the four issues on the table, it seems that only funding to tackle climate change was taken seriously. However, the centrality of the financial issue gave on COP29 ‘a bit of the impression that it was a bankers’ meeting’. On the contrary, what is crucial is the capacity of the countries of the South to face up to the impacts of climate change and achieve ‘their energy and climate transition’ by avoiding recourse to oil and coal, without which the efforts of Europe and the countries of the West would be reduced to nothing. This is not a ‘handout to the countries of the South’, but in everyone's interest.

... or a mockery?

The funding promised for 2035, however, ‘is too little, too late and too ambiguous in its implementation’, declared Ali Mohamed of Kenya on behalf of the African continent, supported by NGOs and other affected countries who consider the agreement ‘painfully inadequate’. It is barely more than the amount [of 100 billion] acquired in 2009, indexed. It's far too little, far too late’, denounced Nadia Cornejo, representative of Greenpeace Belgium. ‘There are no guarantees on the type of financing, which opens the door to loans and private financing, when it is public financing that we absolutely need’. What's more, the agreement does nothing ‘to make the fossil fuel industry pay, even though it is responsible for this crisis and continues to make colossal profits’.

Several countries, led by India, also complained about the lack of inclusiveness, a highly regrettable incident that left them very hurt ‘by what the presidency and the secretariat have done’.

Bolivia, through its spokesman Diego Pacheco, voiced its objection: ‘This agreement only reinforces an unfair system in which the developed countries shirk their legal obligation’, and do not respect ‘the principle of common but differentiated responsibility’. The Nigerian representative called it an affront: ‘Is this a joke?’ she asked angrily. ‘We do not accept this decision! And Malawi, for the group of least developed countries, expressed ‘reservations about accepting’ the conclusions.

Has being the COP29 a by sight trip?

So what is the nature of the agreement, and what impact will it have on our planet?

COP28 in Dubai spoke not of a ‘phase-out’ but of a ‘transition’ for fossil fuels, and activists and NGOs were hoping to obtain clearer commitments on this subject from COP29, which in the contrary - according to Greenpeace Belgium - ‘ratified the carbon market mechanisms, offering an unacceptable loophole for polluters’. There is not a single word in the text of the agreement on the monitoring of efforts to make the transition away from fossil fuels (coal, oil and gas), which is what the Europeans were hoping for. Yet 2024 is likely to be the hottest year on record, and the use of fossil fuels continues to rise around the world.

No wonder.

Since COP15, the COPs seem to be navigating their way through dangerous rocks, a pale icon perhaps of the failings of the UN itself. It is indeed somewhat ironic that, in order to agree to reduce or even eliminate fossil fuels, the host countries of the latest COPs are the Emirates, Azerbaijan and Brazil (COP30), which are going to increase their fossil fuel production between now and 2035. According to Transparency International and the Anti-corruption data Collective, corruption was threatening the Baku COP long before it began. And it was not for nothing that there was a massive presence of fossil fuel lobbyists (over 1,770) in Baku.

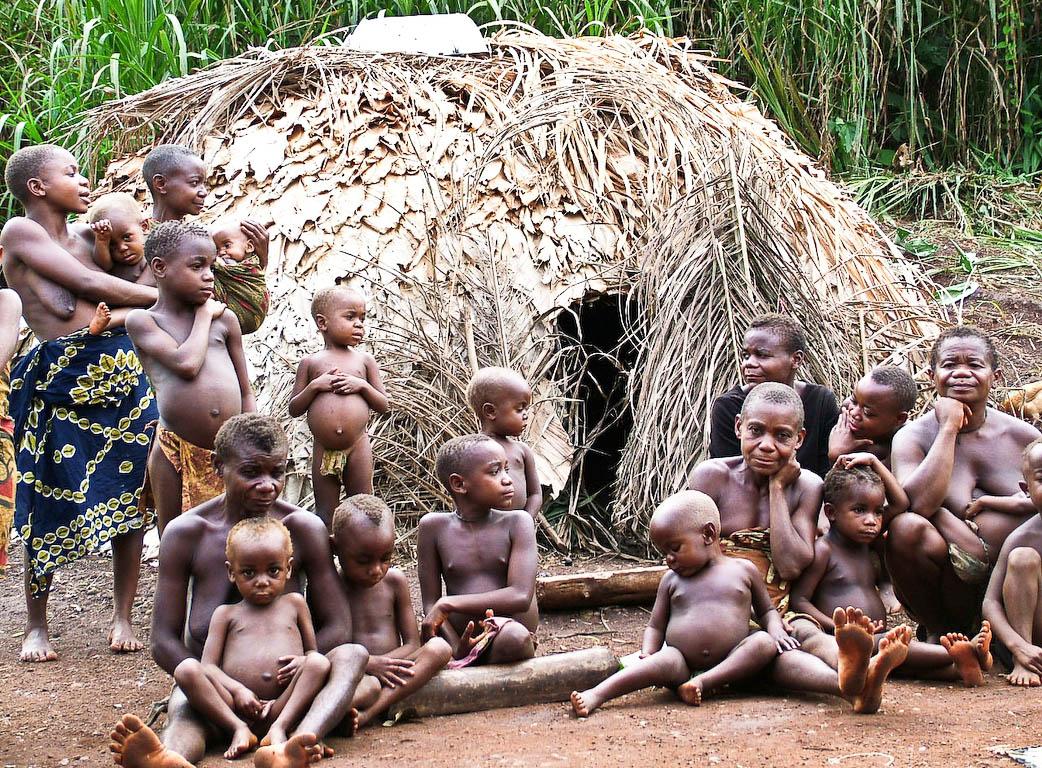

The Baku climate agreements seem to be aimed solely at the rich countries, which have built their progress on fossil fuels, to make them responsible for the climate crisis and accountable to the poor countries that are suffering the most from the consequences. It's a kind of fair climate tax. However, many of the governments of the supposed ‘receiving’ countries are considered to be corrupt, have no commitment to the good of their people and are reluctant to take action against ambient pollution: Kinshasa (Capital of the Republic of Congo) is the one of most polluted cities in the world. All the more reason to remain sceptical about the future.

There were, however, two small bright spots at the end of these days of bitter confrontation.

The $300 billion is part of an appeal ‘to all actors’ to increase climate financing to ‘at least $1,300 billion per year by 2035’, ‘from all public and private sources’. To this end, a roadmap will be drawn up leading up to COP30 next year in Belem (Brazil), with the aim of achieving these 1,300 billion dollars.

Azerbaijan has launched the Climate Finance Action Fund (CFAF), which aims to provide for annual contributions of USD 1 billion from countries and fossil fuel companies to finance renewable energy projects in developing countries.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment