Hypocrisies or Lies?

Etats Unis 14.02.2025 Manariho Etienne Translated by: Jpic-jp.org"One Day, One Map: What Drives the M23 Rebels to Conquer Territory in the DRC? Rwanda's Security or Congolese Minerals?" (Factus). Everyone is now asking this question, as well as another: How far does Rwanda intend to go helped by the M23?

With the capture of Goma, Bukavu, and Uvira by the M23 and the Rwandan army, old spectres and old lies resurface. In discussing, explaining, and attempting to clarify the failure of MONUSCO in Congo, the existence of the March 23 Movement, analysing the conflicts in eastern Congo and the Great Lakes region, and the unconditional support of the West for the Kigali regime, we always return to the massacres in Rwanda in 1994.

In this confused situation, where the incompetence and corruption of Congolese authorities and the questionable human rights record in Burundi further obscure the data, everyone is free to express their opinion. Having lived for several years in Burundi and even longer in the Congo (DRC), knowing Rwanda very well, having spent about a decade as a civil society member at the United Nations, and having worked as an editor for a specialised African review, I have endeavoured to follow the political and military developments of the African continent. I allow myself to share my opinion—undoubtedly subjective—which took time to shape, as I am surprised that three key aspects of this conflict are never considered.

The Root of the Problem

When discussing the war between Russia and Ukraine, history, past conflicts, and mistakes in peace processes are examined. Regarding the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, reference is made to the conquest of Jerusalem by the Romans, Turkish rule, and British protectorate in the region. However, when it comes to conflicts in the Great Lakes region, discussion often stops at the massacres or the 1994 genocide in Rwanda without looking further.

Yet, everything began in Rwanda with the 1959 to 1961 Hutu revolt against centuries of Tutsi domination, which resulted in several thousand victims and thousands of Tutsi refugees fleeing to Burundi, Uganda, and Tanzania. A young Rwandan Tutsi refugee I met in Bujumbura in 1969 told me: "This revolt was not inevitable, but it had become necessary."

It was from Uganda, in fact, that the Tutsi army invaded Rwanda. In the first clash, they were halted near the northern border by the Rwandan regular army and Mobutu’s Congolese paratroopers. Their commander, Fred Rwigyema, lost his life there, giving space to Kagame to emerge as the new leader and to the UN to send an interposition force, UNAMIR (United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda).

From this position, while infiltrating commandos to provoke an already exasperated Rwandan population, Kagame was merely waiting for a pretext to override UNAMIR. The pretext came on 6 April 1994: the plane carrying the President of Rwanda, Juvénal Habyarimana, and the newly appointed new Burundian President, Cyprien Ntaryamira, returning from peace talks in Arusha, was shot down. The Hutu people’s reaction was brutal, undoubtedly fuelled by Hutu political and military figures, and killings spread across the hills.

But who shot down the plane? "Kagame. He told me so himself in response to my question," assured Théogène Nsengiyumva in an interview we had in the United States. Nsengiyumva is one of four Tutsi generals who abandoned Kagame after realising he was a "killer mind" - he was then sentenced to 24 and a half years in prison for high treason by Kagame’s regime.

Nevertheless, after 6th April, Kagame waited several weeks before resuming his invasion, reaching Kigali, and stopping the massacres. Confronted with this fact, Canadian Colonel-General Roméo Dallaire, then head of UNAMIR, confessed at the end of his 500-page book Shaking Hands with the Devil, published a decade later: "I then wondered if Kagame had not deceived us all." Read in context, this suggests that Kagame allowed the Hutu peasant’s massacres to continue to prevent any moderate Tutsi resistance to his armed intervention and to build the "saviour" image that would grant him long-standing influence on the international stage.

The Overlooked Case of Burundi

The historical trajectories of Burundi and Rwanda have always been intertwined. Under Belgian protectorate, the two countries were known as Ruanda-Urundi. The Kirundi and Kinyarwanda adjective-pronoun "undi" means "other," playing on words this suggests that Burundi is another Rwanda. Since the 1960s, however, both nations have experienced repeated and parallel ethnic tensions: while in Burundi, power remained in Tutsi hands, in Rwanda it was controlled by the Hutus. A glance at the dates raises a question:

- 1 October 1990: The Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) invaded Rwanda from Uganda against the Hutu regime of President Habyarimana.

- 1 June 1993: Melchior Ndadaye is democratically elected as Burundi’s first Hutu president, defeating the ruling Tutsi-led Uprona party.

- 20 October 1993: A coup by the Tutsi-led Burundian army assassinatesd Ndadaye to restore Tutsi power in Burundi.

- 6 April 1994: The Rwandan and Burundian Presidents’ plane is shot down, triggering massacres that justified Kagame’s takeover with his Tutsi army.

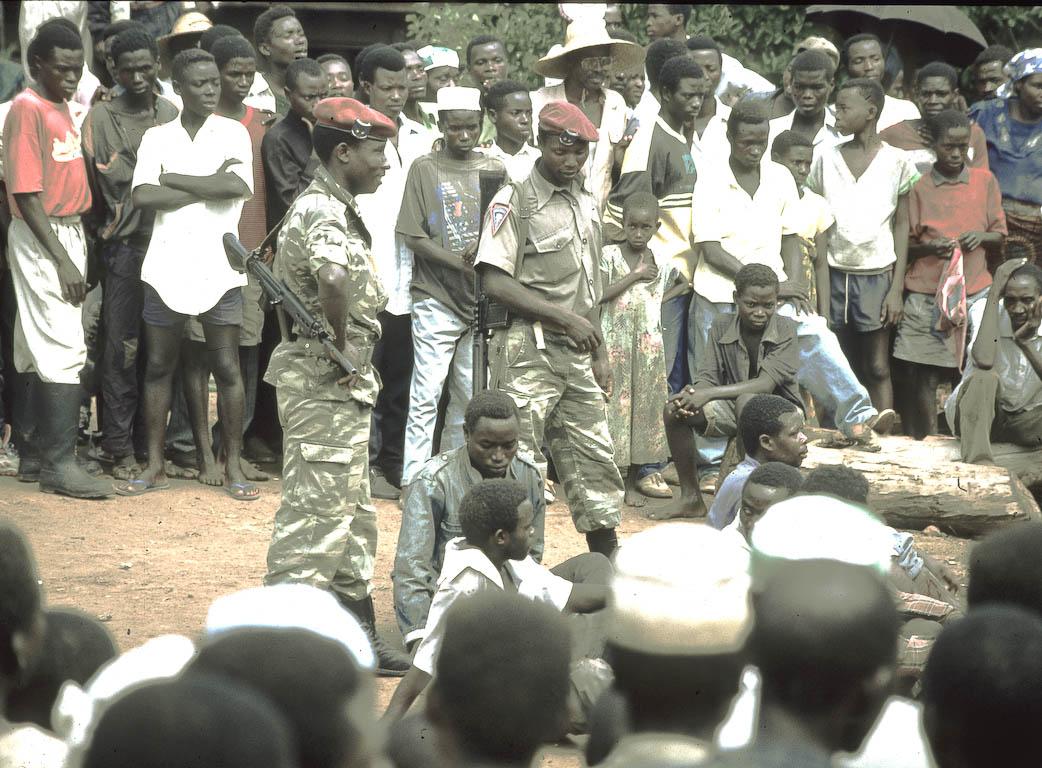

Having lived in Burundi for a long time, I was in Rwanda on 23 October 1993. Descending from Cyangugu (Rwanda town), I headed to Bugarama on the Burundian border, where Hutu refugees fled in fear after the coup and Ndadaye’s assassination. I stopped at the Catholic Parish of Mashaka, where three Tutsi priests kindly granted me access to their house and offered the church in Bugarama as a shelter for Hutu refugees. Before I left, the eldest priest pleaded: "Father, please hear my confession—perhaps my last. What is happening in Burundi is the bell tolling for us Tutsis of Rwanda”. Clear reference to Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, a macabre omen, for in Burundi, the coup d'état had provoked a reaction from the Hutus peasants who, on the hills, had massacred with machetes some one hundred Tutsis, or even many thousands. How can one overlook Burundi’s ethnic conflicts when trying to understand those in Rwanda?

The Tutsi Dream

“Does Rwanda have clear territorial ambitions in eastern DRC?” Is it merely the "Balkanisation" long denounced by Congolese bishops and international bodies, or is it something more?

It was in Nairobi in December 1994, when I first heard of the "dream of a Tutsi empire" from European and African intellectuals at the New People Media Center: The Rwandan invasion was then seen but the first step, and the Burundian coup an occasional misstep. Was that merely a paranoid mind-set of overzealous journalists? By no way.

General Nangaa, the new Congolese figurehead covering up the Rwandan invasion through the M23, recently declared that the plan is to reach Kinshasa. Certain dates seem telling:

- 18 October 1996: Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi (where the Tutsis are once again in power), supporting the rebellion of Laurent-Desiré Kabila, invade Congo—marking the start of the First Congo War.

- 17 May 1997: They seize Kinshasa, installing Laurent Kabila as president and forcing him into agreements over the exploitation of the country.

- 2 August 1998: Rwanda, backed by Uganda, launches the Second invasion of Congo, accusing Laurent Kabila of failing to honour the agreements. Kabila manages to hold power with the direct support of Angola, Zimbabwe, and Namibia, and indirect backing from Chad, Sudan, and Libya.

- 16 January 2001: Laurent Kabila is assassinated under murky circumstances.

- 17 January 2001: Joseph Kabila succeeds his father as President of the DRC and establishes new agreements with Rwanda.

From this point onwards, Congolese politics becomes increasingly tangled: April 2003, a transitional government is formed, incorporating warring factions; 30 July 2006, the first multiparty presidential election since independence is held, and Joseph Kabila is elected president; 28 November 201, Joseph Kabila is re-elected in contested elections, notably criticised for his close ties with Rwanda; December 2016: Kabila’s mandate ends, but Kabila refuses to step down or organise elections; 30 December 2018, Félix Tshisekedi is declared the winner of the long-overdue presidential election, following a deal with Kabila and Rwanda; May 2020, a governmental coalition is born between Kabila and Tshisekedi’s parties; April 2021, in what looked like a political coup, Tshisekedi breaks free from Kabila’s coalition and establishes his "Union Sacrée"; March 2022, suddenly, the M23 rebels resume clashes with government forces. Events then accelerate:

- 20 January 2024: Félix Tshisekedi is sworn in for a second presidential term, vowing to end insecurity in the east and rid the region of Rwandan presence;

- August 2024: Fighting between the national army and the M23 escalates;

- October 2024: Negotiations between Presidents Tshisekedi and Kagame collapse;

- January 2025: Goma falls, marking the beginning of an outright war.

Conclusion

My opinion, undoubtedly subjective, is that from the very beginning, the issue at stake was the ambitious dream of a Tutsi empire conceived by the Tutsi elite exiled in Uganda. Yoweri Museveni, during the struggle for power in Uganda against Milton Obote first and later against Tito Okello in the 1980s, appointed Kagame as head of military intelligence – Kagame’s role was crucial in the victory that brought the National Resistance Army (NRA) to power in 1986. Then Museveni endorsed the invasion of Rwanda, planning the realisation of the Tutsi dream. The plan has so far failed due to circumstances. Is it resurfacing now, and why?

Without absolving either individuals or the various governments of responsibility for their actions and positions, the once widely accepted narrative celebrating Kagame as the exemplary African head of state and the "saviour of the Rwandan people" is increasingly tarnished. The trial that convicted Auguste-Charles Onana nevertheless allowed for the contestation of the "existence of a crime" of Tutsi genocide. The book Rwanda: Assassins Without Borders. Investigation into Kagame's Regime by Michela Wrong, once favourable to Kagame, while not denying the genocide, offers serious criticism of Kagame as Rwanda’s liberator. The number of "Tutsi" victims has been revised down from 1.2 million to 800,000, a significant portion of whom were Hutus, even raising the hypothesis of a second genocide. The self-defence of the Tutsi regime against the FDLR (Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda), supposedly former Hutu Interahamwe génocidaires, is growing weaker as time moves further from 1994, and its substitute justification - the defence of the Banyamulenge - exhibits several flaws. International opinion, influenced by numerous United Nations declarations, is now fully convinced that Rwanda’s presence in Congo only serves to appropriate the region’s mineral wealth, and so the European Community is tempted to disavow the agreement with Kigali on rare earths.

However, why now? Does Putin not claim the right to seize at least part of Ukraine, and Khamenei to be the master of the game in the Middle East? Does Trump not speak of annexing Canada and taking Greenland? Does Israel not aim to cleanse Gaza and occupy the West Bank? Why not a Rwandan protectorate over Congo, or at least its rich eastern region, especially if, in the name of human rights for the "poor oppressed Tutsis" in Burundi, the political situation there would be overturned?

Conspiratorial thinking has never changed history, but it has often paved the way to actual conspiracies. Think of the Julius Caesar’ assassination on the Ides of March, that of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in June 1914, which triggered the First World War, those of the Kennedy brothers in the United States, the planned massacres of Muslim Pakistanis in India, which shaped the partition of India in 1947 and led to the Bangladesh War in 1971. Moreover, the states’ borders, established after the Second World War and the independence movements of the 1960s, are being redrawn once again all over the World: why not in the Great Lakes region?

Locked away in the archives of the United Nations still lies the black box of the plane that crashed on 6 April 1994, containing the evidence to support the claims of Théogène Nsengiyumva. International opinion and the governments that show him friendship and respect would then recognise him as the instigator and intellectual author of the massacres, or even the genocide(s) in Rwanda, and the thousands of deaths and millions of displaced persons in Congo. Friends will distance themselves from the hypocrisy of silence to keep their financial interests. Another king in history will stand exposed naked: today, perhaps, there is Kagame’s last chance to win his poker gamble – the Tutsi dream.

Photo. Bugarama (Rwanda). Hutu refugee camp, November 2993.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment