The Recovered Genocide

Mundo Negro 10.09.2021 Carla Fibla García-Sala Translated by: jpic-jp.orgGermany will compensate Namibia for crimes committed between 1904 and 1907. Germany has taken more than a century to acknowledge that it committed genocide in Namibia by annihilating 80% of the Herero population and 50% of the Namas. Avoiding talks of “reparation” or “compensation”, Berlin announced that it will deliver 1.1 billion euros over the next 30 years to the Namibian government.

Facebook became a center for reactions, criticisms, demands, questions, and laments. Last June, the reproduction of the first page of the weekly The Patriot left no doubts. As if it were a shopping list, it offered an official breakdown – made a few years after the negotiations began in 2015 – of the cost of the Nama and Herero genocide committed at the beginning of the 20th century: loss of life (10.792 million euros), loss of livelihood (2.124 million), loss of land (1.618 million), forced labor (14.074 million) and other costs (700 million). In total 29.269 million euros. “What has happened in three years that made the value go from 29.200 million to only 1.100 million?” asked the businessman and activist Vetumbuavi Green Mungunda.

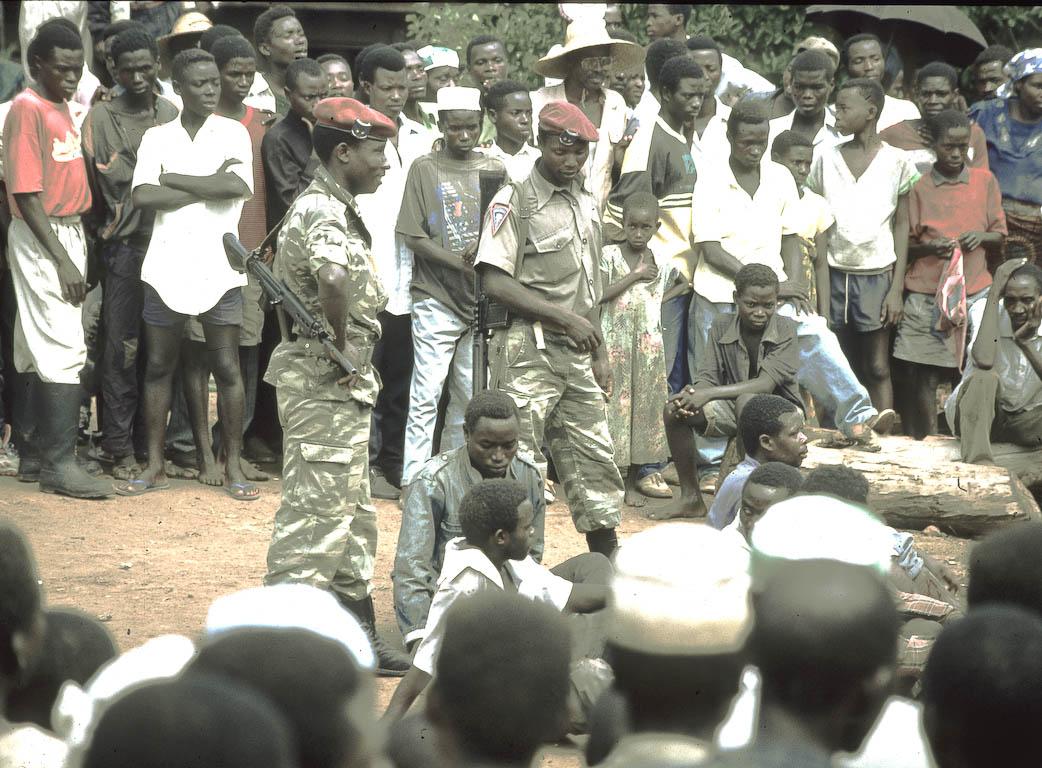

Academic Ngondi Kamatuka was also responding to the announcement of the agreement between the governments of Namibia and Germany by hanging on his wall a black and white photograph of a group of Herero survivors on their return from the Omaheke desert, where they had been abandoned by German troops. Seven men, some still with a baby face, with the ribs completely marked and the skin stretched over the bones, and two women unable to stand upright.

It all started in 1884, when the European powers divided up the African continent at the Berlin Conference. Thus began the “Scramble for Africa”. Germany was left with present-day Cameroon, Togo, Tanzania, and the southwest coast was also annexed, what is now Namibia. The conditions to which Germany subjected the population until the 1st World War made the Hereros, commanded by Chief Samuel Maharero, along with the Namas, on January 12, 1904, rise up against the occupation under the proclamation of “Let us die fighting.” The response of the colonial forces was brutal, according to historians of the time, who would later qualify what happened as the first genocide of the 20th century.

80% of the Herero population, 65,000 people, and 50% of the Namas, 10,000 people, died in a confrontation that lasted from 1904 to 1907. Those who managed to survive were transferred to the Omaheke desert, where many died of starvation, thirst, exhaustion or because of the bullets and cannons with which they were still being attacked. Women were systematically raped, and those who made the way back were again intercepted and transferred to camps where they were used as slave labor. One of the most important concentration camps was located in what is now Swakopmund, the main seaside resort in the country.

There were specific extermination orders for the areas in which both communities were concentrated, which, according to the historical accounts of the time, explains the destruction of even what was essential for the lives of Hereros and Namas. This forceful act, carried out in response to the attempted uprising, also affected other groups, such as the Damaras, whose estimated population before the war was 30,000, and which was reduced to 18,487. According to an official census of 1911, after the genocide, 19,423 Hereros and 14,236 Namas remained alive –some historians dispute this figure lowering it to 10,000 – in the territory that bore the name of German South West Africa.

The columnist Kwame Opuku analyzed in detail the terms used to communicate the agreement between Germany and Namibia and strongly criticized the fact that the German action in the southern country could be justified just because at that time there was no legal framework on genocide. “Germany seems somewhat reluctant to recognize the genocides of 1904-1907 fully as such as it is in International Law (…) by saying ‘Now we will officially call these events of the colonial period what they are from today’s perspective: a genocide.’ So, it is suggested that in the past, such deliberate murder of a people, their extermination, in some way, was not against International Law. In fact, the 1945 Genocide Convention has no retroactive effect. However, even the genocides of the Hereros and Namas were not within any provision of International Law, they were against the duties of Germany as a colonizing power.”

Lack of transparency

Germany’s initial allegations, pointing out that the actions of their ancestors was “something that was done wrongly” – historians and the accounts of the relatives of the deceased showed that a “disintegration of institutions, political life, social, language, dignity, health and even the life of each individual” – show how twisted this approach has become.

In 2015, Germany officially called the events “genocide” but refused to pay reparations. This is how an arduous negotiation began, one in which both community leaders and organizations that defend the memory of the Hereros and Namas or their descendants have been excluded.

They were not at the negotiating table, and they do not know how the reparations’ money will be distributed, as Germany announced, it is invested in infrastructure, medical care and training programs that benefit the affected communities.

Sources critical of the process not only come from Namibia, but non-governmental organizations such as Berlin Postkolonial, also referred to the “lack of transparency”, by not having included victims’ associations. “Without the descendants of the groups most affected at that time, without them, there is no reconciliation. It is unthinkable”, they explained on social media.

Instead, Heiko Maas, German Foreign Minister, in a statement released on May 28, said: “I am grateful for having agreed with Namibia on how to handle this dark chapter of our shared history. After more than five years, Ruprecht Polenz and his Namibian counterpart, Zed Ngavirue, concluded the negotiations conducted on behalf of both governments with the guidance of both Parliaments. Representatives of the Herero and Nama communities were involved in the negotiations on the Namibian side.” It is another misperception, from the perspective of those who questioned the agreement, that it has not allowed such a deep historical wound to begin to heal.

The Namibian government has requested that the economic aid be used for “land reform – 25 million hectares were confiscated, the most fertile land in the country, which has not been returned to most of its owners – including its development and that of agriculture, and the rural world. The loss of 80,000 animals is estimated; the Namas lost most of their livestock – water supply infrastructures and vocational training is marginalized in areas where, at the moment, around 100,000 Herero live – the total population of Namibia is 2.5 million people. In fact, if the genocide had not occurred, according to the calculations of the Namibian Executive, today there would be at least 954,903 more Namibians who would be part of its census, and the Hereros would be the largest community.

The issue of the distribution of reparations also provoked virulent reactions on social networks, from which the German Government was accused of controlling this aspect as well, and of doing so in such a way that “the current settlers” continue to increase their fortunes and well-being in Namibia. The debate about the distribution and who should benefit in Namibia will drag on because the country is going through a financial crisis, it has one of the highest levels of inequality in the world, which leaves little room for maneuver. Namibia is a large nation, its surface is equal to that of Germany and Italy combined, but also depopulated. At the moment, 7% of its population are Herero and 5% Namas.

An insult

Chief Paramount, Vekuii Rukoro, leader of the Herero, and Goab J. Isaac, who is in command of the Namas Traditional Leaders Association, rejected the deal, calling it a “sale.” Shortly after it was made public, they expressed their rejection because accepting it would be “a betrayal of their ancestors.”

“What Germany offers is not enough. They have no right to sit and talk about us without us and come out with a sold-out deal that says nothing. A genocide that allows Germany, as part of its own discretion, to agree to deliver money in exchange for bilateral projects. That is not what we have in mind. The aid must go directly to the descendants of the victims of the genocide, as stipulated by Uahamise Kaapehi, the municipal council that chairs the Herero-Nama Committee in Swakopmund”, stated Vekuii Rukoro, lawyer and former parliamentarian, shortly before his death, the past June 18th, from Covid-19. “We are not so stupid that we cannot control our own money. We want Germany to respect us. We demand an apology from the Germans and let them be the ones to buy farms for the descendants,” he concluded.

This idea is agreed by Nandiuasora Mazeingo, director of the Ovaherero Genocide Foundation, who described the agreement as “an insult” because the Government of Namibia was given the role of “facilitator” in the process and the affected communities were directly excluded. He recalled that the amount offered is equivalent to the annual budget of the Namibian Ministry of Education, and wondered without waiting for an answer: “Is this what they offer after they have killed 80% of my people and 50% of the Namas? They have plundered our country and their children still sit on our land.”

From the Namibian Government, its spokesman, Alfredo Tjiurimo Hengari described the recognition as “a step in the right direction”, because “although there is never a way to conclude or close the issue, because no one can close a genocide, we are happy to let the Germans take responsibility of it.”

New relation?

Namibia, the largest producer of marine diamonds and the fifth largest producer of uranium in the world, passed from German to South African hands because the neighboring country defeated German troops and assumed control of the territory until its independence in 1990, in which the action of the militias of the Southwest African Peoples Organization (SWAPO) was crucial.

Very few analysts believe that, despite the historic gesture that signifies the official recognition that a genocide was perpetrated against the Hereros and Namas, this will mean a rapprochement or the beginning of a healthy relationship between both nations. Distrust and, above all, conflict management, remove any hint of mutual understanding.

How much is a person’s life worth? How to compensate for the destruction of a society? The forgotten genocide of the Hereros and Namas has achieved, with the gesture of the German Government, international recognition, and visibility, but it is far from occupying its rightful place within Namibian society. “It is not enough”, was the most repeated phrase said by activists, politicians, and descendants of both communities.

No “restorative justice agreement with Namibia” has been negotiated that will allow progress on the pillars of a solid relationship of trust. Gestures and images continue to dominate the complex relationship between the former colonizer and colonized. Therefore, the 20 skulls that a Berlin hospital returned to Namibia a decade ago, after acknowledging that they were sent to Europe to be studied and thus demonstrate the superiority of whites over blacks, exemplify that Namibians were never treated as people, they were victims of persecution and extreme violence. What is also evident is that superiority that the facts demonstrated de facto, not only manifested itself in the past, but has been made explicit in the present, how the opportunity for a recognition and full agreement helping to mitigate the crime committed is missed.

See the original article: El Genocidio Recuperado

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment