They have kidnapped Europe

Repubblica.it 10.06.2024 Alessandro D’Avenia Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThe winds of war blowing in Europe today in fact show a discouraging weakness of political imagination and diplomatic discourse, and repeat what has always led to disaster in history: in the absence of real bonds, one targets an enemy, believing that war, not words, can give 'unity' to those who do not have it.

European Parliament: where do these two words come from? It is a story of blood and dreams, as human history always is. Let us start with the myth.

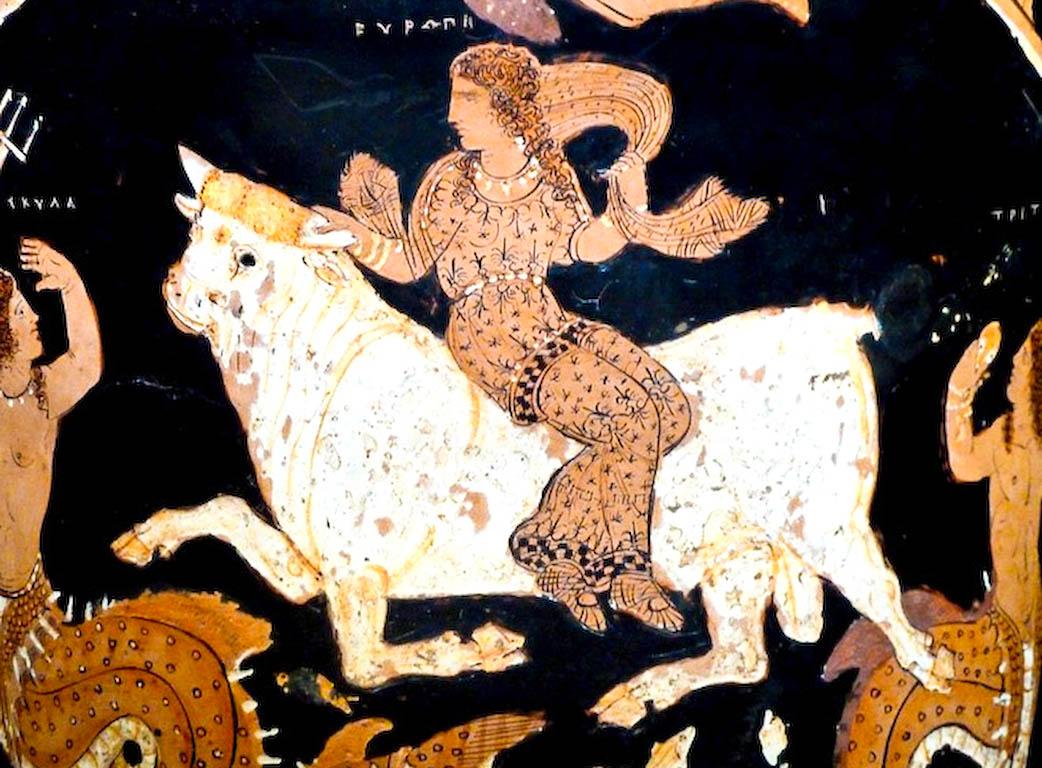

Europa, beautiful daughter of the Phoenician king of Tyre, saw a white bull appear on the beach. Intrigued, she climbed onto the back of the prodigious animal that entered the sea and carried her westwards to Crete. The bull turned out to be Zeus who violated her. Europa never returned and the West, where she had disappeared, took her name.

Herodotus, a Greek historian, in the 5th century BC, searching for the remote causes of the rivalry between East and West says that the myth conceals less prodigious but equally bloody facts: the Phoenicians had kidnapped the Greek princess Io and the Greeks, in revenge, had taken the daughter of the Tyre’s king, Europa. Thus began the chain of vendettas and kidnappings that, passing through the Trojan War, would culminate in the Persian wars, won by the united Greeks (Thermopylae, Marathon, Salamis...) against the invader. A geopolitical clash that for Herodotus had in the Bosporus area the hinge: on one side Asia Minor, the Persians, on the other Europe, the Greeks.

But how could the name of a kidnapped girl become the adjective qualifying the parliament for which 370 million people from 27 countries were called to vote? The origin of the name Europa is uncertain, but it indicated the place where light was seen to disappear, of the Sun or of a girl. Is Europe then just a west for those in the east, or a vocation and therefore a task?

Herodotus asks this question and states that the difference between (minor) Asia and Europe and the cause of their rivalry was the form of government: the Persians submitted to despotic kings, the Greeks to laws. Subordination versus isonomy (equality before the law). The historian found the unifying element of the Greeks in the defence of freedom: this had given them the strength to defeat an empire as powerful as the Persians.

However, Greece would enter a crisis not even a century later, precisely when the union of its city-states crumbled and, for the sake of rivalry and dominance, committed suicide in a fratricidal war that weakened them to the point of handing them over to another king, the Macedonian Philip, father of Alexander the Great.

The legacy of the Greeks was then developed by the Romans, who geographically and politically created Europe as we understand it, building the borders of a civilisation with a system: of laws at the basis of our law, of administration and of communication (roads and language) that was extraordinary. But Rome, too, collapsed amid civil wars, rivalries of generals and the follies of emperors, and then the barbarians did the rest, although they preserved some of the structures of the empire.

At this juncture, the glue for Europe became Christianity. How? In 476 A.D. the last emperor of the West, a teenager, was deposed, disorder was spreading through the ruins of the empire. Benedict, a young man born in Norcia in 480 A.D. to a wealthy family, had left for Rome for his studies and left it in chaos, but had kept it in his heart and mind. Retreating to the Apennines of Latium, he created communities guided by his Rule (same root as reggere), summarised as: ora et labora, 'pray and work'. Thanks to these two inseparable imperatives, monks and lay people from neighbouring lands formed a community in which it did not matter whether they were free or slave, noble or peasant, learned or ignorant, Roman or barbarian: everyone, inside and outside the monastery, collaborated.

This art of living harmonised spirit and body, eternity and time, nature and work, tradition and invention, individual and community, as the living masterpieces of the Benedictine tradition show: Citizen plants that we admire today in the virtuous synthesis of built-up area and countryside, viticulture and beekeeping, medicinal and officinal art with plants, farming of difficult terrain, an embryonic system of deposits and loans, scriptoria for copying and meditating on ancient texts, the education of children, the architecture of abbeys, daily rituals preserved in words such as breakfast, dish, lunch... Europe became, as the great sociologist Léo Moulin says in The Daily Life According to St Benedict: "A network of model farms, centres of breeding, hotbeds of culture, spiritual fervour, art of living, will to action, in a word, high-level civilisation emerging from the tumultuous waves of barbarism. St Benedict is undoubtedly the father of Europe”.

From these seeds would blossom the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, which would make Europe a masterpiece and a bulwark against invasion, this time by Islam.

There is therefore no Europe without adding to the legacy of Athens and Rome that of Jerusalem, that is, Judeo-Christianity. Unfortunately, however, the Europe of national egoisms and religious wars betrayed this composite soul. It is no coincidence that a genius such as Novalis in 1799, upset by the bloody political fragmentation due to the Napoleonic wars, taking up the European humanist tradition (Erasmus of Rotterdam, Pico della Mirandola), wrote Christendom or Europe, in which he sought the lost soul of the continent. A proposal that went unheeded, with the result of exacerbating the national divisions that would lead to the tragic history of the 20th century.

To make Europe, therefore, a common currency is not enough, a common soul is needed: otherwise a living (social) body is not given. Europe is not the sum of national egoisms but a symphony: what is the sheet music?

Europe would not establish itself as a superior identity, still impregnated with colonial and war mentality. Europe would not establish itself as an imposition of rules dictated by the strongest economies. Europe is not established itself without Ukraine, but neither is it established without Russia, because as John Paul II repeated, it is one from the Atlantic to the Urals. Europe would not establish itself without a shared policy on migration. Europe would not establish itself as a branch of NATO but as a pole of a multipolar geopolitical tension. Europe would not establish itself without a clear regulation of the enormous capital flows managed by the few economic groups and companies that now dominate the world economy. Europe would not establish itself without the union of Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox churches.

But this remains utopia without a common language: a new ability to 'speak' to each other. Even the 'parliament' (the place where one 'speaks') is a Benedictine invention: the 'parliamentum', in medieval Latin, was in fact the supranational assembly of the abbeys.

Does the one in Brussels speak this common language? What soul unites me with a Frenchman, a Hungarian, a German, a Pole... so much so that I feel they are part of my same (social) body? Erasmus and roaming are not enough. In fact, the winds of war blowing in Europe today show a discouraging weakness of political imagination and diplomatic speech, and repeat what has always led to disaster in history: in the absence of real bonds, one targets an enemy, believing that war, not speech, can give 'union' to those who do not have it. The myth was not wrong: Europa still remains the girl of the ancient tale: kidnapped westwards. Is saving her a dream or our calling?

See, Hanno rapito Europa

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment