Africa. Congo's mineral wealth has become its curse

Avvenire 28.01.2023 Francesco Gesualdi Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgCobalt, copper, gold, diamonds: mining is increasingly controlled, yet extortion, corruption and violence 'crush' artisanal miners and thousands of children

Because of its mineral wealth, the Democratic Republic of Congo DRC), which Pope Francis has just visited, plays a strategic role in the international economic chessboard. In addition to diamonds and gold (ranked fourth and sixteenth in terms of production, respectively), Congo is strategic for cobalt, copper and coltan (columbo-tantalite), three minerals that underpin the energy and technological transition. Cobalt for battery, copper for electrical equipment, and coltan for electronic components production.

The main mining areas in Congo are Katanga in the south and Kivu in the east. In Katanga, mainly cobalt and copper are mined, in Kivu coltan, gold and diamonds. Official sources estimate that overall, the mining sector contributes 18% to the Congolese gross product; however many think this an underestimation considering that a large part of Congo’s mining is done informally. Just as much of the trade takes place in the form of smuggling. Especially in Kivu, where countless armed groups of the most diverse origins dispute its richness, that has been the clashes scene for decades. On 22 February 2021, even the Italian ambassador, Luca Attanasio, along with his bodyguard Vittorio Iacovacci, lost their lives in this region, ambushed by one of the many-armed gangs infesting the area, each with different aims and affiliations. Some are more structured and linked to neighbouring countries’ movements such as Rwanda or Uganda, if not to internationalist movements such as the Islamist ones; others are more extemporaneous, responding only to the ambitions of chiefs and ringleaders, eager to assert their own space of power and to accumulate wealth through extortion, kidnapping or smuggling of mineral resources.

Aware of the strong link between the trade in minerals from Kivu and the use of their proceeds for the purchase of weapons by the various factions operating in the field, part of the international community has sought to remedy the phenomenon by imposing transparency on all actors in the chain. In other words, every operator who makes use of minerals potentially coming from the Great Lakes area is obliged to trace their route and must account for them publicly. In January 2021, Italy also transposed the European directive imposing this obligation. This is an important step forward; we hope the smuggling machine's ability to falsify documents will not thwart it.

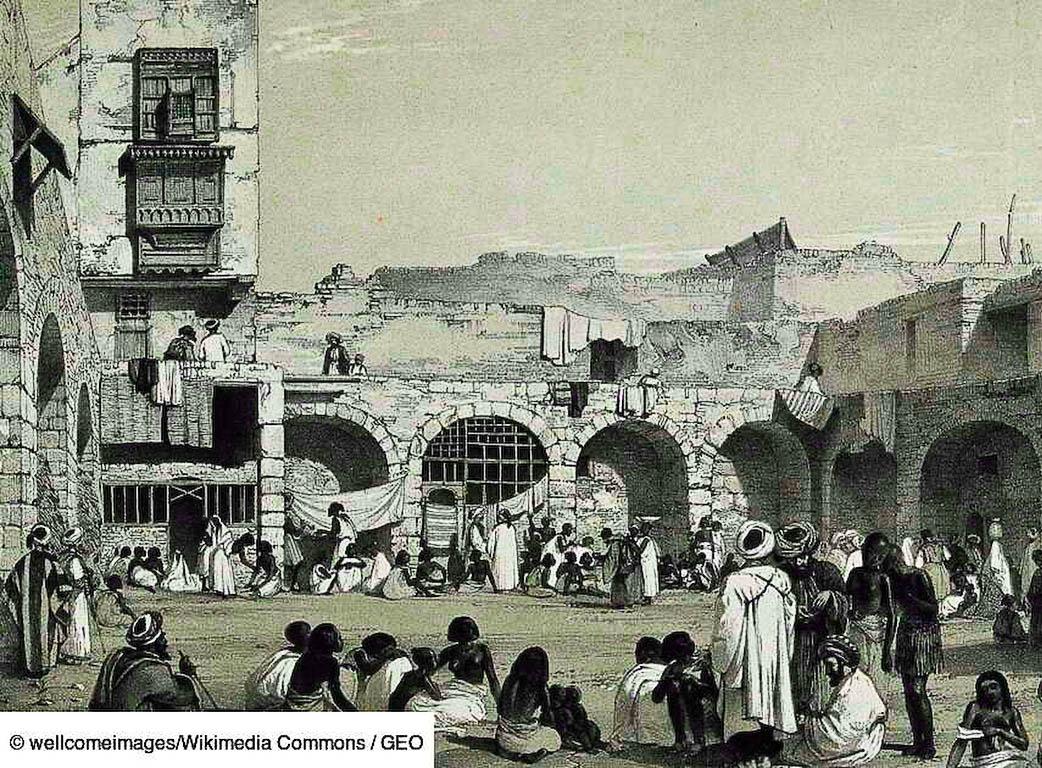

The intermediation chain that brings the minerals from the Kivu underground to the metallurgical companies located in Europe and Asia (US too?) is quite long and it happens that taxes and levies are imposed at each step by the powers exercising control over the territory to get rich through the mineral trade. The extortion starts at the small buyers’ level who buy the raw ore from the miners and continues up to the exporters. In 2007, the humanitarian organisation Global Witness accused Afrimex, a London-based mining brokerage company, of supporting the paramilitary group RCD-Goma through the coltan purchase on which an 8% levy had been imposed by the rebel group. The British section of the OECD, called upon to comment on the case, concluded that 'Afrimex had not ensured that its activities did not support armed conflict and forced labour'.

Paying the highest price for this extortionist system are the small operators at the base of the production and commercial pyramid. In Kivu, extraction is mainly carried out by individuals, the so-called 'artisanal miners', who, once they have identified a site they consider promising, ask the land’s owner for permission to exploit it. They then start mining with the help of people seeking employment. Since this is informal work, no one knows exactly how many artisanal miners there are in Kivu, but it is estimated at several hundred thousand. Subjected to grueling hours and risky working conditions, without any bargaining power, they are forced to sell the proceeds of their labour at the prices set by local wholesalers, as long as the local military power does not misappropriate what they have extracted. According to the value reconstruction carried out by various organisations, the miners get an average of 1% of the output value from the smelters, in the case of coltan, and 0.8% in the case of casserite.

What is worse, according to the October 2021study by the Institut d'études de sécurité, a large part of coltan is extracted with the labour of more than 40,000 children and adolescents. Originating from Kivu’s remote villages, poverty causes them to abandon school, which they have often never attended, to seek work at the mining sites where they are destined to crush and wash the minerals. When they can, they also engage in petty trade and sell coltan for derisory sums in towns along the Burundi, Rwanda or Uganda border.

Working as adults in unhealthy environments causes them serious health problems. Occupational hazards include daily exposure to radon, a radioactive substance also associated with coltan, which causes lung cancer. Being alone in unfamiliar environments, in addition to the abuse and violence risks, children are also exposed to human trafficking and to recruitment by armed groups as child soldiers.

If we leave Kivu and move to Katanga, we find a very different production situation. Here, large mines dominate, run by Chinese, Canadian, South African and European multinationals. Nevertheless, we find many problems typical of Kivu. For example, the artisanal miners’ phenomenon, who extract about 20 per cent of the cobalt, is also highly developed in this area. Although the artisans’ activity is more controlled here, the law violations are still numerous. For example, in August 2016, and again in November 2017, Amnesty International reported a large presence of child labour in the cobalt mines: between 20,000 and 40,000 minors subjected to unspeakable conditions. The news put the entire production chain in trouble, from multinational mining companies, to traders and to manufacturing companies using cobalt to make batteries for their products. These companies include electric car, smartphone, and computer companies. At first, the line of defence was that industrial and artisanal mining have nothing in common.

Then it was admitted that the boundary between the two is very blurred because many artisans dig in areas owned by big companies and sell what they extract to the latter, as if they were working as subcontractors. It is no coincidence that the London Stock Exchange, where the world's major mineral and metal trading takes place, is now demanding traceability reports from its members. Meanwhile, a case, initiated by the US Department of Justice and concluded in May 2022, found that Glencore, the Swiss multinational operator of eight copper and cobalt mines in Katanga, paid $27.5 million in bribes to Democratic Republic of Congo’s officials between 2007 and 2018 to obtain illicit economic advantages.

According to the UN, corruption is a monster devouring 25% of government revenues worldwide. It is calculated that in African nations with the highest levels of corruption, governments spend 25% less on health and 58% less on education due to corruption. Which helps to understand why despite its enormous wealth, the Democratic Republic of Congo is one of the five poorest countries in the world. According to the latest data from the World Bank, 64% of the Congolese population lives below absolute poverty with less than USD 2.15 a day. There is a concrete demonstration of how minerals end in the enrichment of the few, effectively turning into a curse for the many.

See Africa. La ricchezza mineraria del Congo è diventata la sua maledizione

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment