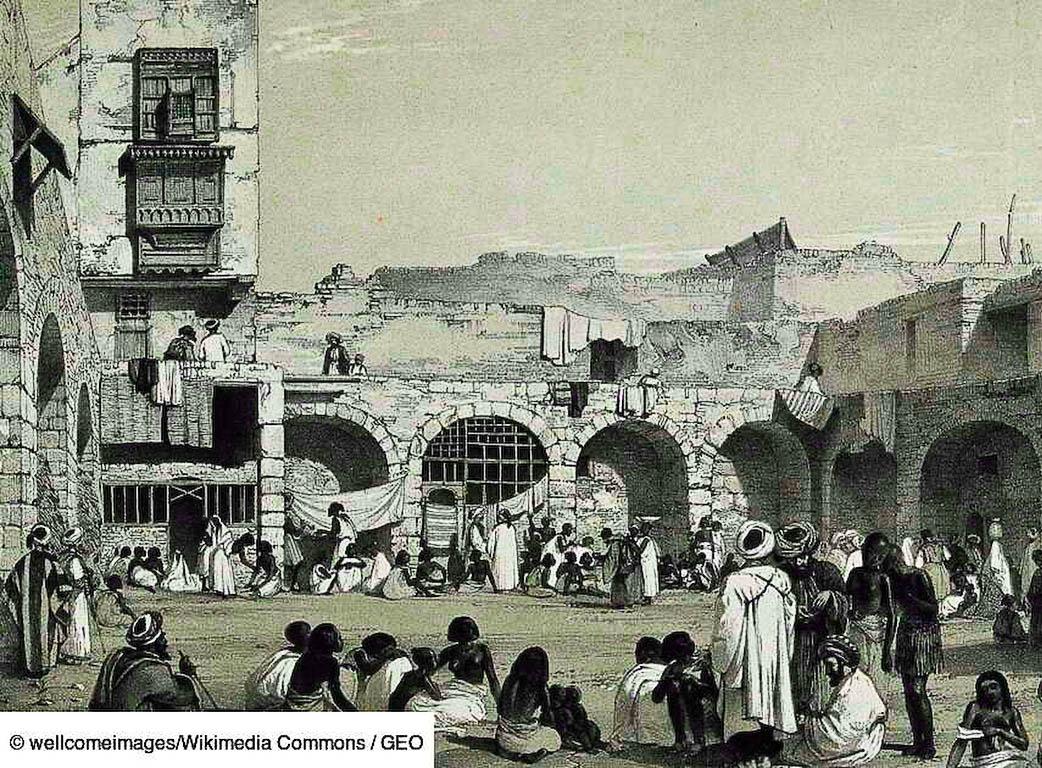

Slavery in the Muslim world

GEO Histoire 20.01.2025 Boris Thiolay Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgEurope did not have a monopoly on the slave trade: between the 7th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the Arabs and Ottomans conducted raids in sub-Saharan Africa and Europe to supply the Muslim world with slaves. This is the little-known story of millions of slaves over the centuries. Eight questions and answers to gauge the scale of the phenomenon

To what extent was the Arab-Muslim conquest based on slavery?

Shortly after the death of the Prophet Mohamed in 632, Muslim armies began a conquest northward, beyond the Arabian Peninsula. They made lightning progress. In 635, they drove the Byzantine army out of Syria and Palestine, taking Damascus, Homs and Jerusalem. Towards the north-east, the Arab conquerors (a few tens of thousands of men) created garrison towns such as Kufa and Basra (in modern-day Iraq), defeated the Persian army and brought about the collapse of the Sassanid Empire in 637. To the west, they subdued Egypt in 641, before continuing their march towards the Maghreb. ‘Against this backdrop of war and territorial expansion, the Muslims took men, women and children into captivity, as was customary at the time, in order to enslave them,’ explains historian M'hamed Oualdi, professor at Sciences Po Paris and author of L'Esclavage dans les mondes musulmans (published by Amsterdam, 2024). ‘This slave labour was used to build or rebuild cities, or to serve Muslim soldiers and their families.’

The slave trade began in 652, when General Amr ibn al-Nasr, conqueror of Egypt, demanded that the Christian king of Nubia (modern-day Sudan) provide him with 350 slaves every year in exchange for peace. Just over a century after the start of the conquest, the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad (750-1258) occupied an immense territory, from southern France and Spain in the west to Transoxiana (modern-day Uzbekistan) in the east, as well as the Caucasus and the Volga basin in the north. At the same time, the pagan populations on the fringes of the empire (white in the Caucasus, black in Africa) were increasingly enslaved.

Did Islam authorise enslavement?

Like Judaism and Christianity before it, Islam does not prohibit slavery. This practice, considered to be part of the divine order of things, is even legitimised in several suras of the Koran, as well as in the hadith, i.e. the collection - written down in the 9th century - of the sayings and actions of the prophet Mohamed (around 570-632), who himself owned slaves.

However, Islam introduced new rules, putting an end to debt bondage and forbidding a bonded woman to be forced into prostitution. It was also forbidden to mistreat or kill a slave. Freeing a slave is considered a good deed or an act of expiation and is strongly encouraged. Islamic tradition highlights the case of Bilal ibn Rabâh, a black slave from Ethiopia who was freed around 615 by the Prophet's father-in-law and became the first muezzin - the one who calls the faithful to prayer. Another essential prohibition: a Muslim may not reduce another Muslim to servitude. However, this last rule was to be broken countless times over the centuries.

Were black people considered inferior at the time?

Islam itself does not establish a hierarchy between believers on the basis of their skin colour. And the biblical account of the curse of Ham (for disrespecting Noah, his own father, he was banished, his complexion darkened and his descendants condemned to become slaves) does not, in Islamic tradition, justify the enslavement of black people. But the Arab conquerors did enslave pagans captured on the fringes of the Dar al-Islam (‘house of Islam’), especially in Africa. Bilad as-Sudan, the ‘Land of Blacks’, thus became a major breeding ground for the slave trade.

From the 10th and 11th centuries onwards, the conversion to Islam of sovereigns and then of sub-Saharan populations once again raised the question: could black Muslims be enslaved? Specialists in Islamic jurisprudence systematically replied in the negative. However, the great slave traders continued to justify enslaving Blacks, pagans or anyone who was not Muslim enough in their eyes.

How widespread is this trade?

According to studies, the total number of people enslaved in the Muslim world between the seventh century and the beginning of the twentieth century varies from 12 million to 17 million. The duration of these trades, the multiplicity of routes, the variations in their scale over time, and the lack of written sources in certain regions explain this variation of around 25% in the number of victims. One thing is certain: the trans-Saharan slave trade was the largest in number - perhaps as many as 9 million people - and the deadliest of the Arab-Muslim trades, with possibly a million deaths along the caravan routes. The slave trade in the Red Sea and from the Swahili coast is estimated to have claimed a total of 7 million victims.

The number of captives from the Caucasus and the Balkans is not precisely known. As for the Europeans captured by the Barbary pirates in the Mediterranean between the sixteenth and late eighteenth centuries, the most recent studies put the figure at 850,000. This was less an organised trade than a race war involving attacks and raids on enemy ships, and some captives could be freed for ransom. However, more reliable figures give an idea of the overall scale of the trade in the 19th century alone: 442,000 East Africans were sold in the Indian Ocean, and a further 492,000 were transported from Ethiopia to the Middle East via the Red Sea. Finally, 1.2 million people from West Africa were transported to the Maghreb and Egypt.

What were captives used for?

Captives were assigned to three types of work and functions. The vast majority were used for domestic slavery. In every palace and every house of notable people, there were servants, both men and women, assigned to specific tasks: black maids in charge of cleaning and maintenance, eunuchs, most of whom were black, gardeners, clerks and bodyguards. The fate of concubines varied greatly, ranging from sexual slavery to the status of favourite or even wife: white women (Italians, Circassians) or certain Abyssinians (Ethiopians), for example, were prized for their beauty.

Another, more unexpected function was ‘administrative slavery’ or ‘government slavery’. At the court of the Abbasid caliphs (750-1258), and later the Ottoman sultans (1299-1922), pages, valets and even eunuchs, who developed a close relationship with the sovereign, were able to rise to high office over the years. From the 9th century onwards, the caliphs of Baghdad recruited young, fair-skinned boys from the Caucasus and Georgia to form their personal guard. These mamelukes [possessed, in Arabic] were converted to Islam and trained in the art of war, then freed to become military cadres, including generals,’ points out historian M'hmed Oualdi. ‘Muslim rulers did not trust local subjects and were wary of internal plots. These slaves, who came from outside and had no local family ties, had only one loyalty: to their master, the sovereign.’ The programmed social rise of the Mamluks - individuals who had experienced servitude and then exercised command over free men - is a very special case. A dynasty of Mamluk sultans ruled Egypt, the Levant and part of the Arabian Peninsula from 1250 to 1517, forming the most powerful Muslim state of its time.

Finally, black men and women were rounded up in West Africa and on the eastern coasts of the continent and enslaved to do back-breaking agricultural work. The best-known example is that of the Zanjs, a mixture of African and Arab-Persian populations forced to reclaim swampy areas in what is now southern Iraq. Similarly, the Saharan and Egyptian oases, then the coffee, cotton, tobacco and groundnut plantations established in the 19th century on the coasts of East Africa (in today's Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique) and in the short-lived Sultanate of Sokoto (1804-1897) in northern Nigeria, were also major centres of forced labour. The Muslim world saw the development of slave-owning societies, rather than fundamentally slave-trading societies,’ continues M'hamed Oualdi. ‘Apart from the large plantations in East Africa, where 40% to 60% of the population were slaves, slave labour did not exceed 5% of the total population.’

What was the status of these slaves?

Considered as both a person and a thing, slaves could be owned by one or more masters, sold, hired out or given away. In theory, slaves had to eat the same food as their owners, but this was very rarely the case. They also have the right to marry and own property, with the agreement of their master. However, if he has no offspring, everything reverts to his owner in the event of his death. As emancipation is encouraged by Islam, a slave's status may change over time. However, in accordance with the ‘right of patronage’ inherited from ancient Rome, the master retains authority over his former slave.

By converting to Islam, a captive increases his chances of being freed: he may be freed by his master on his deathbed, in a final gesture of penitence. In addition, male servants who stood out for their intelligence and loyalty could be given positions of responsibility. Within the household, these might include, for example, guarding the seal authenticating the master's letters or, in the case of eunuchs, ensuring that no foreign men had access to the harem, the living quarters of wives and concubines. Other trusted servants might be sent on mission, to deal with commercial matters or to levy a tax on an agricultural estate. Some enslaved women were also likely to see their status evolve. Concubine slaves, known as jawaris, could become wives and then be freed if they gave birth to a child for the master of the house’, explains Jamela Ouahhou, a specialist in medieval Islam at the Institut de recherches et d'études sur les mondes arabes et musulmans. ‘They were then referred to as the ‘mother of the child’ (umm al-walad) and the child was free.’

‘There are examples of concubines who became sovereigns, such as Chajar al-Dourr in the 13th century. She was a slave from the Caucasus or Asia Minor and a favourite of Sultan al-Salih Ayyoub, from whom she had a son, and was freed before becoming his wife. After the battle of Mansourah (Egypt) against the crusaders in February 1250, which she led alongside two military advisers, and the death of the sultan, Chajar al-Dourr was appointed sultan on 4 May 1250 by the amirs and Mamluk generals. Her regency was short, but the sources attest that she exercised some form of power until 1255’, explains the historian.

Are there any known cases of rebellion against slavery?

There is only one recorded case of collective revolt: that of the Zanjs, in the 9th century, in what is now southern Iraq. This population, a mixture of East Africans and enslaved local tribes, was tasked with reclaiming and draining the marshy areas of the Euphrates and Tigris basins, turning them into farmland. In 869, the Zanjs, subjected to appalling living conditions, rebelled against the power of the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad and led a guerrilla war, even going so far as to take control of certain towns. This revolt was put down in 883, after large-scale massacres.

In addition, ‘slaves who were able to move about in public could go and consult a faqîh, a specialist in jurisprudence, to protest against their living conditions’, points out Jamela Ouahhou. One case will go down in the annals of history: in the 13th century, a group of slaves who had fled the estate of their master, the Tatar (an ancient Turko-Mongol people), in Crimea, travelled all the way to Cairo to find Ibn Taymyya (1263-1328), a famous and very rigorous Islamic judge. ‘Arguing that their master, a bad Muslim who drank and did not practise prayer, was mistreating them, they were freed by the jurist and this decision had the force of law’, explains the historian.

When did the slave trade end?

Under strong pressure from the British abolitionist movement, slavery in Islamic lands came to an end in Morocco, the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922) and Persia in the 19th century. In 1820, the Ottoman Empire, whose power was declining, first banned the sale of Greek populations who had revolted against the Sublime Porte and been enslaved.

In 1846, two years before the second abolition of slavery in France, Ahmed I, the Bey of Tunis, representative of Sultan Abdülmecid I in this autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire, set the enslaved free: 30,000 slaves were freed. The abolition of slavery was extended to all territories within the empire in 1847, and the trans-Saharan slave trade was banned in 1849.

In the mid-nineteenth century, while the Western slave trade was dying out, the Arab-Muslim trade was enjoying a revival on the east coast of Africa, providing labour for the large agricultural plantations. But the establishment of British protectorates in Egypt and East Africa at the end of the 19th century changed that all. Between 1845 and 1876, British ships boarded slave traders' dhows in the Red Sea and freed their captives.

After the demise of the Ottoman Empire, the new Muslim states, under protectorate and then independent, took it in turns to put an end to slavery: Afghanistan (1923), Iraq (1924), Iran (1929). The emancipation movement took even longer in the Arabian Peninsula: 1949 in Kuwait, 1952 in Qatar, 1968 in Saudi Arabia and 1970 in Oman.

Mauritania was the last country in the world to abolish slavery, in 1981. It was not until 2007, however, that the law punished all slave-owners with five to ten years‘ imprisonment, which was increased in 2015 to ten to twenty years’ imprisonment.

See, Esclavage dans le monde musulman : l'histoire méconnue de millions d'esclaves à travers les siècles ➤ Article from GEO Histoire n°79, Les mille visages de l'esclavage, January-February 2025.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment