Becoming reconciled, a path to resurrection.

Newark 26.03.2020 Gian Paolo Pezzi Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThe storybook tells in its stories, that one day the squirrel met the plague - it could be the coronavirus - and asked her, "Where are you going?". "To kill 500 people," replied the plague. After a time they met again and the squirrel scolded the plague: "Lying as always! You killed 5,000, not 500!" "I'm bad, but not a liar," replies the plague. "I killed 500 of them, it's the fear that killed the other 4,500!".

St. Paul also says so, Christ freed us not from death, but from the fear of death! And for this reason, during this time more than ever, celebrating hope, trust and the certainty of the good rising far on the horizon is essential. However, even at a simple glance, it is clear that the anguished desire for a hug cannot be true if it does not imply an open heart to reconciliation: an embrace of peace celebrating reconciliation with a wrong past, a difficult present, an uncertain future. An embrace that brings peace to hearts divided by hatred and revenge, by the evil done and received, by inappropriate gestures and wrong choices, by ambiguous feelings and uncontrolled reactions.

In the Easter climate bursting with spring beauty, breaching in, shaking the numbness and sadness of a pandemic, a memory flavoring such as daily bread makes its way: shared unconsciously but then enjoyed fraternally in joy. A sign of hope and of challenge because the much desired embrace should not be of pure emotion but of full reconciliation.

It all starts one afternoon, in a church whose name we don't need to remember, in already distant past time. They called me to confess some little ones who, the catechist tells me with eyes shining with joy, "I prepared really well". When the last girl approaches me, limping, the catechist whispers: "She has mental problems, she speaks poorly, she is almost deaf, don't ask her any questions." The girl does well, however. Instinctively, when the catechist comes closer to take her back to her place, I ask her:

"And you, are you doing your confession, are you not ?"

"I can't", she replies in an impolite tone.

She is around 18 years old, this girl unknown to me. To repair what is of all evidence a duck, I say kindly:

“It doesn't matter, let's say a prayer together; your catechism's children will be happy."

She kneels reluctantly, I put my hands on her head, I invoke the Holy Spirit and start: "Our Father ...". She follows me in a low voice.

We come to the words "Forgive us our trespasses". She gets nervous. When I go on saying "as we forgive those who", she whooshes a "Never!", and jumping to her feet, shakes her head away from my hands and goes away furious.

The church, with its large space of liturgical assembly, seems enveloping me in an embrace, it is fresh despite the torrid climate of the season. In this late afternoon, it offers a penumbra that invites some reflection. I fell immersed in strange thoughts. I have met a demoniac case that what has just happened brings back to my mind. It doesn't seem the case, though.

It is night now. I'm turning off the lights when the bell rings. In the moonlight, I recognize the catechist's face.

"At this hour?".

"Just a minute, please. I would not be able to sleep without having explained to you."

Reluctantly, I open the door for her. She looks dazed while telling her short story.

"We were a poor but happy family; when I was five years old Dad, to whom I was very fond, left home for another woman. He abandoned me, my sister and mum in dark poverty. My childhood was nothing but suffering and humiliation. Above all, the disappointment of my father's love which had been stolen from me burned inside. I will never forgive him. If God is willing to forgive him, let Him do it, but I will never say those words." And she left.

Five years passed. Every now and then, I wondered whether she had forgotten having shared that sad secret of hers with me, a secret crossing my mind every time I casually met her. Then one morning when dawn was breaking, I am awakened by the furious barking of the guard dog. From the window, I see a terrified shadow perched on the hood of the car parked in front of the door. I go down quickly, grab the hand a shadow holds out to me and save it from the dog's last attempt to bite her.

"Good heavens, what are you doing here at this hour? Calm down. If you don't get afraid, the guard dogs do not do any harm." She is the same catechist of five years ago.

"I come from the hospital - she begins speaking in a restless mood but with a full of light gaze -. A wonderful thing happened. I couldn't go home without telling you." She is in complete euphoria and continues without giving me time to react.

“Three days ago I learned that my father was hospitalized, seriously ill. I do not care at all, my feeling was. Yesterday afternoon they came to tell me, "Your father is dying and wants to see you." Nobody needs to be aware of my hatred, I said to myself. I have to go and I went to the hospital."

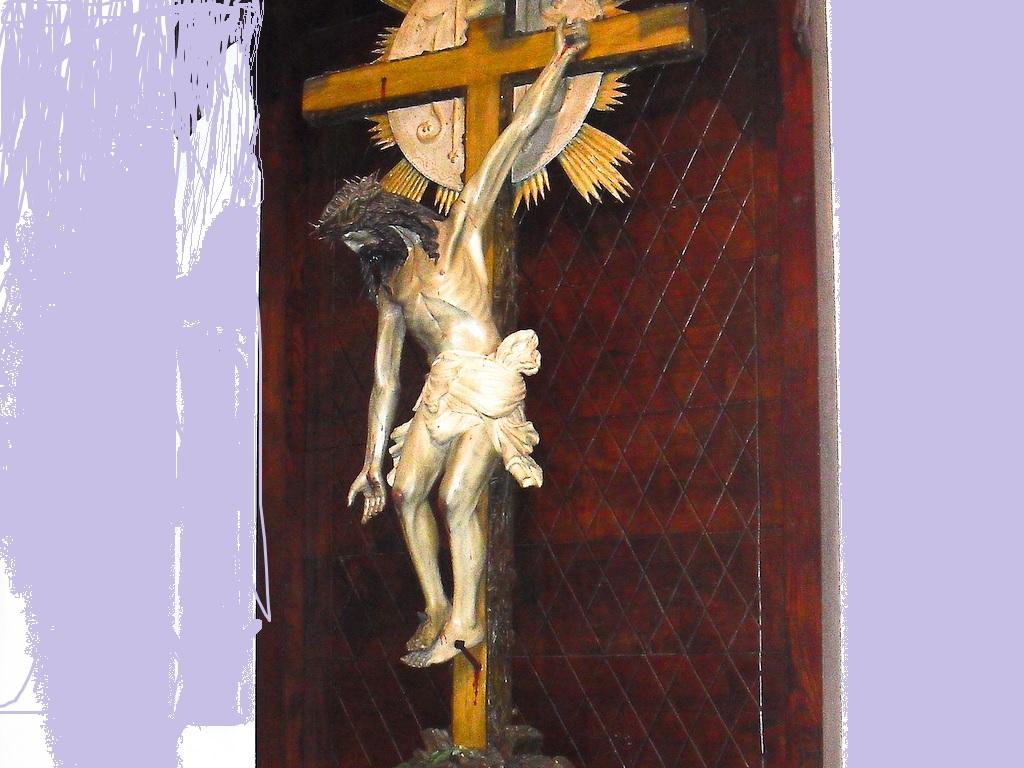

“I was just on the hospital room threshold, when suddenly that afternoon, that our Father of years ago bounced back in my mind. Something inside me was shattered, it was as I finally swallowed a bitter morsel having tightened my throat for too long. I approached that now destroyed old man, I embraced him and spontaneously a word which for years I had denied gushed from my lips: Dad. He began to cry, asked for forgiveness, I cried with him, I forgave him wholeheartedly, we prayed together and at that moment he expired in my arms."

“They kept telling me I had to leave, notify the family, think of the funeral. But first I had to come, to tell you what happened and share with you this great joy, this peace finally found."

St. Augustine, if I remember correctly, says that the Our Father is the measure of true Christian prayer. I always thought it was something more. That day I understood that the Our Father is also the path of returning to peace, of finding ourselves in a much desired embrace, of a long expected communion after a fasting. Waiting for the corona-virus' end, could be celebrating the hope of a new Easter of Resurrection.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment