Here is a child, no matter who he is, for you he is the Emmanuel

Newark - Kisangani(DR-Congo) 25.11.2020 Gian Paolo Pezzi Translated by: Jpic-Jjp.orgIt sounds like the story of a book about Christmas. Instead, it emerges from the worn diary of a scruffy missionary. It is the life of an unhappy girl, lost in the heart of Africa. Her name is Veronica, like the one in the Gospel: a little faith and humanity would be enough to recognize in her the Emmanuel who came to us 2000 years ago.

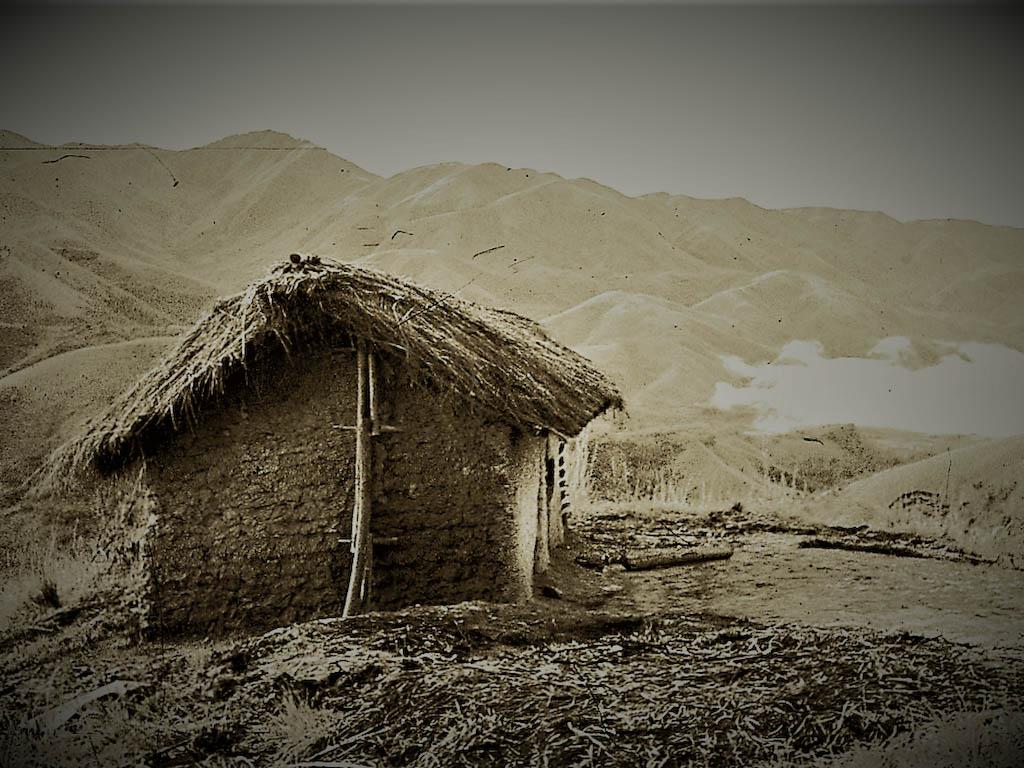

She showed up one afternoon around three o’clock, when the blazing sun makes the air muggy and unbearable in the humid rainy season. Gaunt, with a mat of crumpled banana leaves under her arm and her basket of things weighing on her head, dirty and with an ugly sore under her chin, she gave off no beauty. “I don’t know where to sleep and I’m hungry,” was her opening line. Sitting in front of the parish’s office, she was waiting for the Caritas mothers to ask for their help.

When I realized it was too late: a swarm of brats leaving the school had surrounded her and were looking at her with a mixture of curiosity and revulsion, not without disgust and fear. Thus, began to develop a long story, with details that eluded us and that prevented the end from being predicted.

Her name was Veronica, she was thirteen years old, and she had been born a stone’s throw away from the parish. Her dad died when she was little. He was not married to Veronica’s mother, neither by church, nor civilly, nor according to tradition. As there was no link between the parents’ families, they did not assume responsibility for the child. The mother returned to the parental home, left the Catholic Church for a sect and Veronica also lost contact with her baptismal godmother, which in Africa is always a guarantee.

Two years before, the mother had died and a short time later, a malaria crisis, cerebral due to symptoms similar to those of epilepsy, intertwined with her incipient puberty: there were all the ingredients for the drama. Veronica was living with her grandmother and her maternal uncle, who, overwhelmed by the economic crisis and tired of having an extra mouth to feed and medicines to pay for, declared her a mlozi, a witch. The sudden death of his youngest son gave him the authority to report her and throw her out on the streets.

Veronica began to wander from here to there, among strangers and natural relatives, numerous by the way according to African tradition: she always found something to eat, but on the condition that she did not stay around, especially at night.

At the roots of her case, other stories of witchcraft appeared; all referring to children and elderly women. The documents in the parish archives bear witness to this. We decided to do something and, to begin with, we enrolled Veronica and put her in the parochial elementary school. The first days went well, then a malaria crisis made her unpopular with her peers. They began to make fun of her and to be respected, she reacted throwing herself to the ground, fluttered, and drooled from her mouth simulating the epilepsy attacks that she knew so well.

We appealed to the Municipality, and to different associations, but without results. With Veronica, it seemed that we had set ourselves on a path that led nowhere. Everyone here “knows” that witchcraft exists; the doubt about whether that girl was a witch was not fading. Her illness, the bad habits that she has contracted during the two years of wandering, and the epileptic gestures that she carried out in moments of fear were the overwhelming proof. It is as if to say: Be careful! Because I am a witch.

The grandmother, the uncle, the relatives, the neighbors, and the district director were convinced of this. More certain than that God exists, is that Veronica is a witch. She was also convinced of it. Under insidious questions she tells who, where, when and how they gave her the ulozi: mlozi is the witch or the sorcerer, ulozi is what makes you like this. According to Veronica, it would have been an old woman who lives on the next street. She gave her the ulozi in a cassava dish. When the old woman was asked, she denied everything.

In the city there is a home for street children run by a priest of the Sacred Heart, but there are no institutions for girls, who, when accused of witchcraft, are between 5 and 13 years old. We found a good mother who was willing to take care of Veronica and we hoped to open a center for homeless girls with her. However, the rumor that Veronica would be one of the girls in the center stifled the initiative before it began. When that lady had a miscarriage, Veronica was naturally singled out as the cause and was sent back to the parish.

Then we were lucky that two old men, brothers to each other, who had no children, visited us. They looked like the Joaquin and Ana from certain Renaissance paintings. They wanted to do something nice at Christmas. So, they welcomed Veronica as a mission that God entrusted to them. We found the right medicine for her epilepsy and Veronica started to feel fine, even wanting to go back to school. Everything was going well. The young girl was blooming again. With an adolescent at home, the two old people were rejuvenating and even the fields, they now worked with two young arms that were getting stronger, were reborn to a new life. Every fortnight they came to the parish to receive help from Caritas and thus increase their scarce food resources.

Every now and then Veronica had a crisis and rebelled herself. One day she told me: “My father went away, my mother is dead, my grandmother and my uncle have thrown me out, I have no brothers or sisters.” This was her problem, the problem of the societies that the dictatorship and poverty have destroyed. Fear and need – when faith is lacking – make us withdraw in on ourselves and incapacitate us to do good. Even in rich countries, wealth becomes a property that must be defended at all costs and against everyone. A fear of the other arises, the sense of solidarity is lost, and one locks oneself in protected areas.

Christmas is the invitation to go outside, the courage to risk life for others, the joy in the certainty of faith and the experience that has its origin in a God who makes himself like us.

The “fish” in the times of persecution was the symbol that allowed Christians to recognize themselves because in Greek the word “fish” is written with the initials of Jesus Christ, Son of the Savior God. Perhaps the symbol of Covid-19, the “mask”, could be an incentive for us to go “outside” today: “The storm unmasks our vulnerability and exposes those false and superfluous certainties from which we have built our agendas, our projects, our habits and priorities,” said Pope Francis on the night of Good Friday, in the midst of a pandemic. Discerning the path to healing and recovery in the midst of this pandemic is certainly not a thing for “lone wolves.”

Later addition. Veronica and her new “parents” were a symbol of Christmas that year: good and faith bring forth life, love and acceptance, where before there was rejection, hostility and death.

Two years passed in serenity, then one day Veronica disappeared. “She was longing for wandering”, the two old people told me sadly. From my part, I moved to another parish in another part of the country. I haven’t heard from Veronica anymore. But every Christmas, her image of a defenseless girl reappears to me like in that muggy afternoon and I wonder if there was anyone who knew how to see the Lord in her.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment