Forward slowly, almost backwards: how is the African economy doing?

Rivista Africa 19.08.2023 Mario Giro Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgGlobal inflation, the debt crisis and falling foreign investment are stifling the continent's economic growth, particularly in its sub-Saharan region. Some countries, however, are performing well. In any case, good administration and political stability are needed

How is the African economy doing? According to the World Bank's latest Africa's Pulse report, the continent is experiencing a diverse situation. Global inflationary pressures, the threat of recession and falling foreign investment have contributed to a weaker-than-usual growth rate in the sub-Saharan region. The combination of resurgent debt growth (particularly foreign debt) and declining investment risks 'losing a decade in the fight against poverty', according to Andrew Dabalen, the World Bank's Chief Economist for Africa. Growth south of the Sahara is projected to slow further, from 3.6% in 2022 to 3.1% in 2023.

Some countries show more resilience

Kenya, Ivory Coast and the Democratic Republic of Congo maintained higher rates of 5.2%, 6.7% and 8.6% respectively in 2022. Even states in greater difficulty in the recent past show improvements, with growth estimates revised upwards, such as Zambia (+0.8 points to 3.9% after default), Mauritania (+1.2 to 5.2%) and Ethiopia (+2.9, to 6.4%, also thanks to the end of the war).

In DR Congo, growth is being driven by the mining industry, particularly copper and cobalt, thanks to the expansion of production capacity and the recovery of global demand, although the instability in the two Kivus bodes ill for the future. Outside this sector, growth remained moderate and consumption limited due to inflation, which reached 13.1% by the end of 2022, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

In Kenya, economic indicators remained relatively robust due to a strengthening manufacturing industry and increased investor confidence due to the credibility of the fiscal stabilisation plan of President Ruto's new administration.

In Ivory Coast, the main growth drivers were the recovery of consumption (supported by a rise in public wages to counter inflation) and public investment. Industry (+8.1%) and services (+6.8%) were also significant.

However, the World Bank notes that, even in countries with a positive trend, governments should redouble their efforts for macroeconomic stability, a modern tax system, debt reduction (especially foreign debt and in particular that contracted with China) and productive investments to reduce extreme poverty and stimulate the economy.

As is well known, over-indebtedness has become a serious problem for more than twenty sub-Saharan countries and this hampers investment and threatens macroeconomic and budgetary stability, already weakened by the pandemic.

Inflation - continental average of 9.2% in 2022 - is expected to remain at least at 7.5% level in 2023, well above the limits set by the central banks. Investment growth in Sub-Saharan Africa will thus continue to decelerate, as it has been in previous years (from 6.8% in 2010-13 to 1.6% in 2022), with a more pronounced deceleration in East and Southern Africa than in West and Central Africa.

The report adds that the 'ongoing decarbonisation of the world will bring significant economic opportunities to Africa': rare metals and minerals will be increasingly needed, for example for batteries. It is of course hoped that this strategic mining sector will be controlled by national institutions and end up less and less in the hands of global traffickers and criminal networks.

The report predicts that, if good policies are put in place, overall these resources could 'increase tax revenues, improve opportunities for regional value chains that create jobs, and accelerate economic transformation'.

As always, data should be taken with caution. While enhancing the value of natural resources offers the possibility of improving the sustainability of public finances and debt, the World Bank warns that this will only happen if countries adopt sensible fiscal policies.

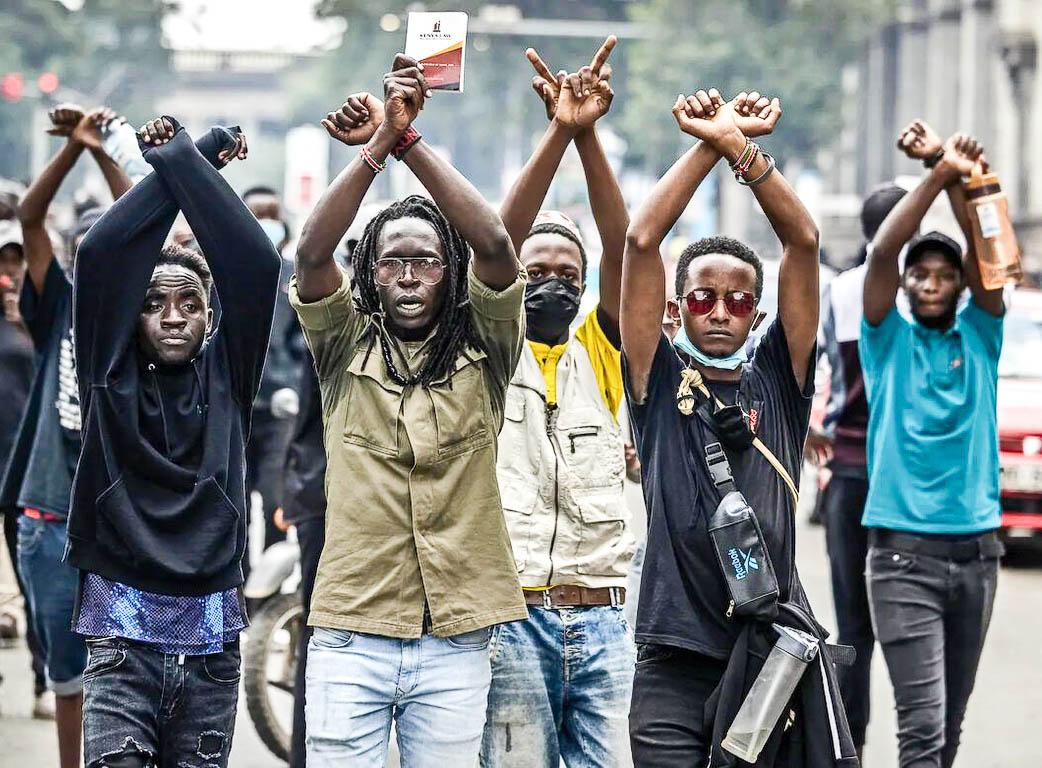

It is no longer the time to suggest policies such as Structural Adjustment Plans. Nevertheless, the Bretton Woods institutions remain of the view that better governance and sound administration are needed in Africa. Over all this always hangs the unknown factor of political stability: in many African regions, the situation may suddenly get out of hand as a consequence of the current global tense situation.

This article appeared in the new issue of Africa magazine.

See, Avanti adagio, quasi indietro: come va l’economia africana?

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment