How Europeans divided Africa and Leopold II got Congo

Itlodeo, l’Utopia che non muore 16.03.2021 Vincenzo Passerini Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgIn the last decades of the 19th century, European countries, through political and commercial confrontations, race, and battles tried to figure out who came first in order to declare “this is mine.” They divided Africa through conferences and treaties. As if everything belonged to them: the people, the animals, the land, the rivers, the mountains, the lakes, the air... and the immense land of Congo became the personal property of the King of Belgium.

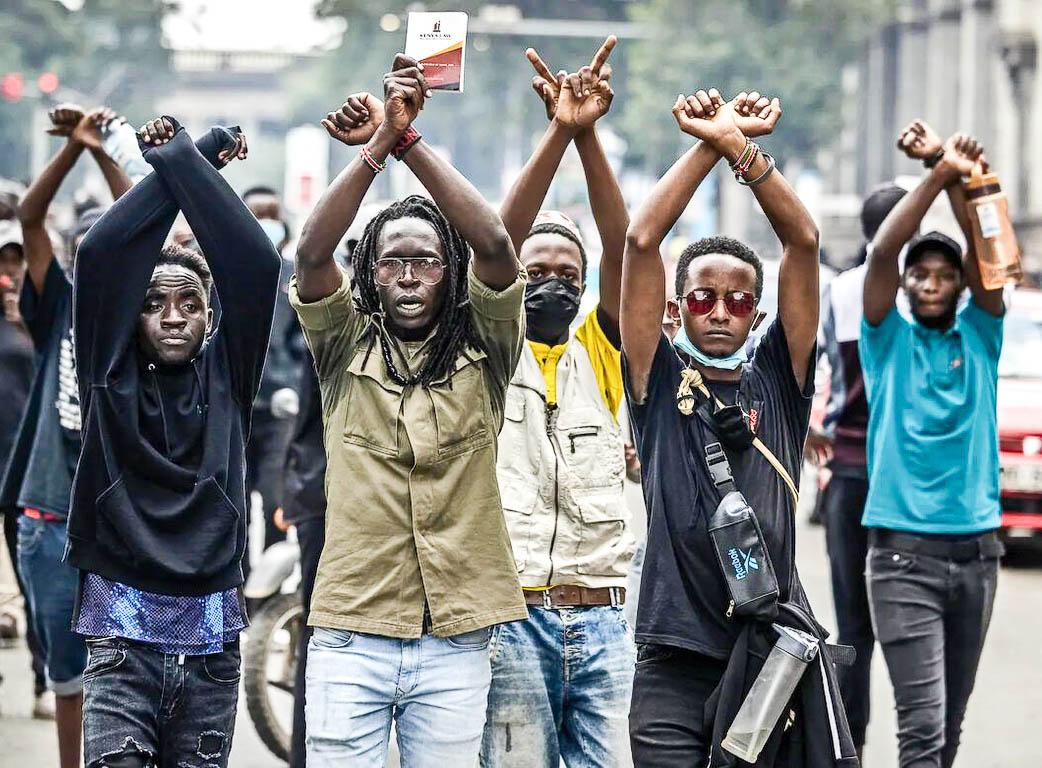

These are pages of history that must not be forgotten and must remind us, facing the Africans who arrive in Europe today as migrants or refugees, or drown in the sea because of the European walls, that we Europeans went to Africa and only left when they finally kicked us out.

The route to Africa

This melee race between Europeans to divide Africa is called with an English expression, the Scramble for Africa. One of the most shameful parts of European history.

Of course, as is the case today, the invasion and partition had to be masked on humanitarian grounds. Thus, it was produced under the aegis of the so-called “three Cs” that Europeans “had” a historical mission that God and destiny entrusted them, to take to Africa with: civilization, Christianity, and commerce – and so, they took all of Africa.

One of the most recurrent motives for the humanitarian propaganda of European colonialism was the elimination of slavery. In their name, Europeans enslaved Africans in modern but no less brutal terms. In 1880, Europeans occupied a tenth of Africa: twenty years later, they had taken all of it. Except Liberia (a nation founded by freed North American slaves) and Ethiopia, later occupied by the Italians.

The partition as described by Martin Meredith

Martin Meredith, a British historian, published the book The State of Africa, a History of Fifty Years of Independence (London, Free Press), in which, to speak of Africa during the current time, he recalls in the introduction how Europeans divided the continent, and how this partition has created the Africa we know today. Here is a translation, somewhat free, of some passages of the introduction.

The Europeans did not know Africa

In the struggle to seize it at the end of the 19th century, the European powers claimed their right to almost the entire continent. At congresses held in Berlin, Paris, London, and other capitals, European leaders and diplomats negotiated the different areas of interest that they wanted to establish on the continent.

The knowledge of the vast interior of Africa was lacking. Until then, Europeans had known Africa more as a coastal strip than as a continent; their presence was mainly limited to small isolated coastal enclaves used for commercial purposes; only Algeria and southern Africa had larger European colonies in place.

With straight lines, 190 cultural groups were separated

The maps used to divide the African continent were, for the most part, inaccurate; vast areas were described as “unknown land.” When drawing the borders of their new territories, European negotiators limited themselves to drawing straight lines, disregarding the countless monarchies, states and other traditional African societies that existed there.

Almost half of the new borders imposed on Africa were geometric lines, latitudinal or longitudinal lines, other straight lines, or arcs of circles. In many cases, African societies were neglected; the Bakongo were divided between the French Congo, the Belgian Congo and the Portuguese Angola; Somali land was divided between Great Britain, Italy and France. Overall, the new borders separated 190 ethnic groups.

Africa in the early 20th century

A map by Joseph Ki-Zerbo, “Storia dell’Africa nera. Un continente tra la preistoria e il futuro”, Ghibli, Milan 2016, was one of the first stories about Africa written by an African historian, from the point of view of Africans – a very good book that we will talk about again.

In other cases, the new European colonial territories encompassed hundreds of different and independent groups, with no common history, culture, language, or religion. Nigeria, for example, encompasses more than 250 ethnolinguistic groups. Officials sent to the Belgian Congo registered 6,000 domains in the territory.

By the end of the Scramble for Africa, some 10,000 political entities had merged into 40 European colonies and protectorates. Thus, the modern African states were born. On the ground, European rule was imposed both by agreements and by conquest; however, in almost all African colonies there were periods of resistance. Many African leaders who resisted colonial rule died in battle, were executed, or sent into exile after defeat.

Only one African state managed to resist the attack of European occupation during the Scramble: Ethiopia, a former Christian kingdom once ruled by the legendary priest Gianni. In 1896, when Italians – with 17,000 European soldiers – invaded Ethiopia from their coastal enclave of Massawa on the Red Sea, and were defeated by Emperor Menelik. The Italians were forced to confine themselves to occupying Eritrea. However, forty years later, the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini retaliated. Determined to build an empire in East Africa, he ordered the conquest of Ethiopia, using half a million soldiers, aerial bombardment, and toxic gases to achieve it. After seven months of prolonged campaigning, the Italian forces conquered the capital, Addis Ababa, and Emperor Haile Selassie fled into exile in England. Ethiopia became an Italian province and was added to the Italian possessions of Eritrea and Somalia.

End of Martin Meredith’s quotes

The case of Congo

At the Congress of Berlin (1884-1885) – one of the decisive international conferences for the Scramble for Africa – the most skillful figure turned out to be Leopold II, who succeeded in having personal sovereignty over the vast Congo recognized, with all the delegates of the other countries standing up to applaud.

Something unheard of, the king of a small European country who became king and personal owner of another state, indeed of a huge African country, as large as all of Western Europe. It was not the Belgian state that took the Congo, but King Leopold II himself, who said “this is mine.” And the others said “yes, it is yours.” Those others were not the inhabitants of Congo, who were not even seen as interlocutors, but only as objects of conquest. Of course, to make Europeans superior. No one at this noble international gathering, where there were more merchants than ambassadors, used more humane words than King Leopold.

He then demonstrated his ferocity and greed on the ground by appropriating the vast wealth of the country and oppressing the Congolese, as journalists, missionaries and diplomats attested. So much so that it sparked an international campaign of protest, in which numerous writers also participated (from Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of Sherlock Holmes, to Joseph Conrad, author of the memorable Heart of Darkness, as well as Charles Péguy and Mark Twain), which forced him to hand over Congo to the Belgian state in 1908.

Before giving up his “personal property”, King Leopold, who died the following year, burned documents for eight days to erase evidence of unspeakable wrongdoings.

A civilized Congo?

This is how Martin Meredith describes, in the work cited above (p.100-101) the state of “civilization” in the Congo when, after a bloody war, the Belgians are defeated and recognize the independence of this immense country on June 30th, 1960.

“Except at the lowest levels, no Congolese had acquired governmental or parliamentary experience. National elections had never been held, not even provincial ones. The lack of qualified personnel was serious. At the highest levels of the civil service, of the 1,400 posts, only three were held by Congolese, two of them were newly appointed. In 1960, the total number of Congolese graduates was thirty. At the end of the 1959-60 school year, only 130 young people had completed upper secondary education. There was no Congolese doctor, no Congolese high school teacher, no army officer.”

At this point, it is easy to understand how Congo, and many other African states, could not seriously cope with the period of independence, given the state of cultural poverty in which they were deliberately kept by the European colonialists. The education and competence of Africans were a threat to colonial rule, though it ended anyway.

But the Europeans tried by all means to maintain their control over the wealth of the African countries, Congo first and foremost. Both because, as mentioned above, Africans were forced to use them, and because they eliminated African leaders who bothered them, such as Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected leader of the independent Congo. Congo, very rich in all the goods of God, continues to be at the mercy of foreign political and economic potentates in collusion with local oligarchies.

Note. “Congo”, by the Belgian David Van Reybrouck (Feltrinelli 2014), is an impressive account of the tragic history of the colonial occupation of the country. Also noteworthy is Adam Hochshild’s “King Leopold’s Ghost”.

See the original article: Come gli europei si spartirono l’Africa. E Leopoldo II si prese il Congo

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment