Is the digital language also biblical?

Avvenire 22.03.2024 Bruno Forte Translated by: Jpic-jp.org‘Semina verbi’, they are found everywhere. Is there a risk of ‘seeing’ them everywhere even where they are not there? Or is it the vocation of the believer to recognise them even where they are unexpected? Digital language recovers an ancient sense: returning to a lost relationship, re-establishing contact, reopening the languages of communication is not what those who ‘convert’ the code of a file do?

In the search to read some traces of God’s nostalgia in the variegated aspects of today's culture, I would like to recall the universal language that is now more than familiar to a large part of humanity: that of the ‘net’. ‘To save’, ‘to convert’ are among the most frequently used expressions in the computers and web use of, significant to the point of excluding from the fruitful use of internet tools those who do not know how to access the processes they indicate. These key words seem to me to be revealing of an expectation, deep and widespread far beyond the explicit awareness one may have of it. They are words with a strong theological connotation: in the world of biblical faith and related theology, ignorance of the meanings they evoke can compromise the whole, that is, the wholeness and fruitfulness of the approach to revelation, just as the same ignorance in the use of them would compromise the computer functionality at root.

Web and Bible seem, therefore, to similarly need the processes signalled by the verbs ‘to save’ and ‘to convert’. It is this observation, as simple as it is intriguing, that gives rise to the question: are possible longings for transcendence hidden in these terms? And if so, in what form?

I will try to answer these questions through the subsequent examination of the two expressions as they are used in the languages of the Net, then comparing the resulting meaning with the analogous theological meanings of the same formulas.

To save: resisting oblivion has been an anxiety of human thought since its origins. ‘To save phenomena’ is for Aristotle and the great Greek philosophy the task of the logos. There where everything appears to be transience, a fragment that comes from nothing and falls into it, the passion of the philosopher becomes that of resisting decline, of defending the gift or torment of existing. This is why philosophy arises where the threat of inexorable loss appears strongest: ‘the pathos of the philosopher,’ writes Plato, ‘is tò thaumàzeiv’ (Teeteto 155 D), an expression that says as much ‘wonder’ as ‘terror’. Where there is danger, there fear joins wonder, surprise joins fear: there, the greater the need for salvation. ‘Where there is danger, there also grows / that which saves’, recites a couplet by Hölderlin (Patmos, vv. 2-3).

Salvation is defence against nothingness, a bulwark against dissolution, a custodian of being. It is to satisfy this need that writing is born: to stop thought in the signs, to make it ready for new access, new communication. This is the dream of every ‘handwriting’: to save the mortal by stopping it. And yet, the voracity of nothingness seems greedier: Plato understood this in his memorable critique of writing, contained in the final part of the Phaedrus, where he insists that writing is not a ‘drug of memory’ and does not replace its functions. Writing is like a ‘game’ in comparison to the commitment to seriousness that orality implies; Plato even goes so far as to state that he is a philosopher who is able to come to the rescue of his writings by showing their weakness, ‘on the basis of those things of greater value that he has not put down in writing’ (Phaedrus, 278 C-E).

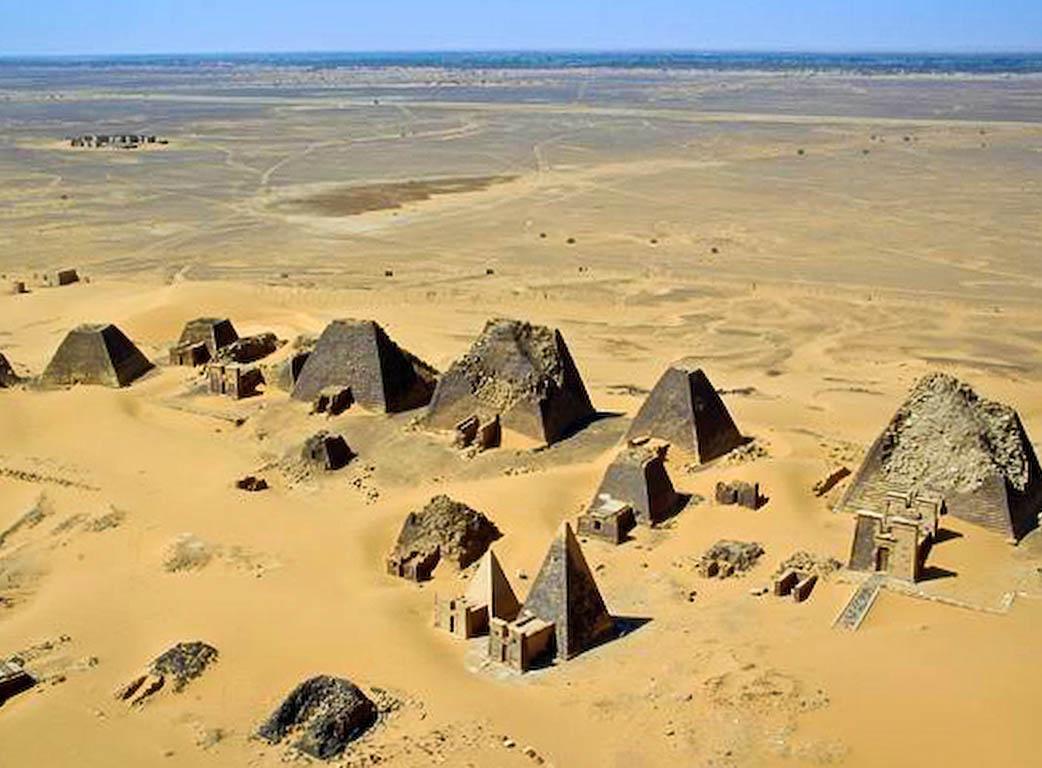

And yet, where oral traditions have been lost, the traces of memory rest on those very monuments, large or small, where writing has saved them. Saving then appears to be a necessary operation, even if not an absolute one: the small salvation offered by writing, that same small salvation that is dictated by the verb to save in computer usage, appeals to an Other, who saves the saved by recalling it, by making use of it, by giving it new life.

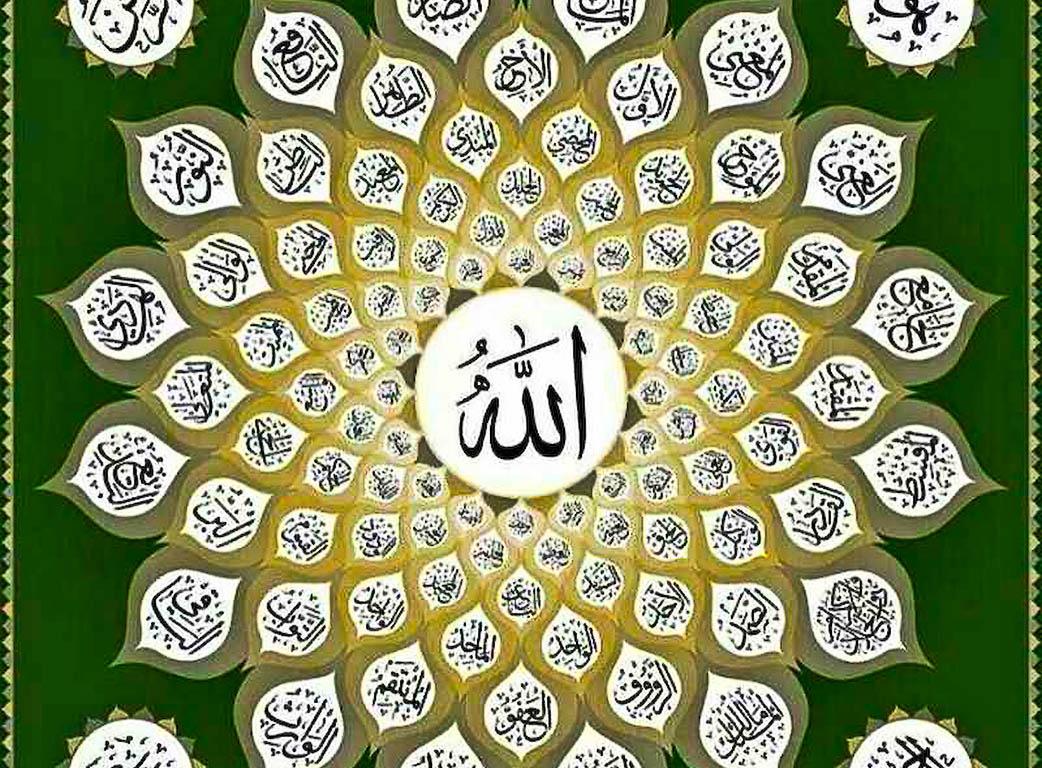

The Other in question according to biblical faith is the Creator and Lord, the Origin and the End, the Custodian and the Womb. The salvation at stake in the words of revelation is not the protection of an hour, of a season, of even infinite time. It is welcome in life without end, it is eternity offered in time.

Of this landing place, the language of the web is a pale trace, a sign of the nostalgia we all have for it. And yet, to save is a sign of transcendence, a sign in the direction of an Other, towards whom we are oriented, for whom we are made. ‘Thou hast made our heart for Thee, and restless is our heart until it rests in Thee": with these words Augustine (Confessions, I, 1) makes himself the voice of an original thirst, that of salvation, and offers himself as the witness of the Other we need in order to live and to die. Every act of ‘saving’ is a trace of this nostalgia that is in us stronger and deeper than any consciousness we may have of it: even the humble process of ‘to save’ linked to the world of the web.

‘Saving’, however, is not enough: if what has been saved could no longer be reached by the continuous evolution of web languages, resistance to oblivion would be in vain. Like any language, computer language evolves and changes: the ‘volatility’ of the material collected and saved appears to be the great weakness of the web world. If the book resists with the palpability of its pages, files live the seasons of the programmes in which they were written. The indecipherability of some writings is already a barrier to the usability of data, which also cost time, ingenuity and effort. It is necessary to ‘save’ the ‘saved’: this ‘saving’ operation squared is the process indicated by the expression to convert. One needs to transfer one language into another, without losing any of the original data.

‘Convert’ is also in the world of the web the expression of the struggle against the passing of time, aimed at expressing the lordship of continuity over fragmentation and the leaps in the ingenuity and creativity of human subjects. Where ‘to save’ denotes the custody of the present, ‘to convert’ signals the possibility of creating bridges between the solitudes saved.

To save is the victory over the transience of the instant: to convert is the triumph over the incommunicability of later times and the mutual strangeness of places and subjects.

This is actually also the original meaning of the expression in the biblical tradition: teshuvà, the Hebrew word translated as ‘conversion’, means the act of returning. While the Greek metànoia and Latin conversio make conversion an act of the subject changing his mind-set or directing his steps elsewhere, the Hebrew makes it clear that conversion is the event of a rediscovered relationship.

This is clearly shown by the evangelical transposition of the idea of shuv - ‘return’ and teshuvà - ‘conversion’ in the parable of the Prodigal Son or the Merciful Father (cf. Luke 15). The language of the web recovers this sense: returning to a lost relationship, re-establishing a meaningful contact, reopening the languages of communication is what is done by those who ‘convert’ the code of a file into another that makes it readable. Of course, in the digital world, it is a matter of different times expressed in different languages, made accessible to the current user. In the world of faith, the rediscovered relationship is that of man with the God of mercy and forgiveness. The analogy is, however, no less important: as in the biblical universe, so in the digital world ‘to convert’ is the process that testifies to the vital importance of the relationship and communication between different people.

To read in the lemma to convert the nostalgia for a rediscovered and re-established relationship is, then, much less than arbitrary. Though, in computer languages, the need for salvation and reconciliation - more than one might suppose - manifests itself in the depths of our restless hearts, today as yesterday and always: we all carry within us, whether we are aware of it or not the need and expectation of the Other, from whom we come and to whom we are called to return...

See, Cattolici e cultura. Il teologo Forte: anche il linguaggio del digitale è biblico

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment