‘Oppenheimer’ reminds us of some crucial moral absolutes

Catholic Herald 24.07.2023 Anthony McCarthy Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgOn August 6 1945, President Truman, when told that the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima had been even more “conspicuous” than the test bomb in New Mexico, announced to Captain Frank Graham, “This is the greatest thing in history”.

In June of that year Henry Stimson, US Secretary of State for War and a key adviser on the use of this new weapon, recorded an exchange with Truman: “I was a little fearful that before we could get ready the Air Force might have Japan so thoroughly bombed out that the new weapon would not have a fair background to show its strength”, at which the president “laughed and said he understood.”

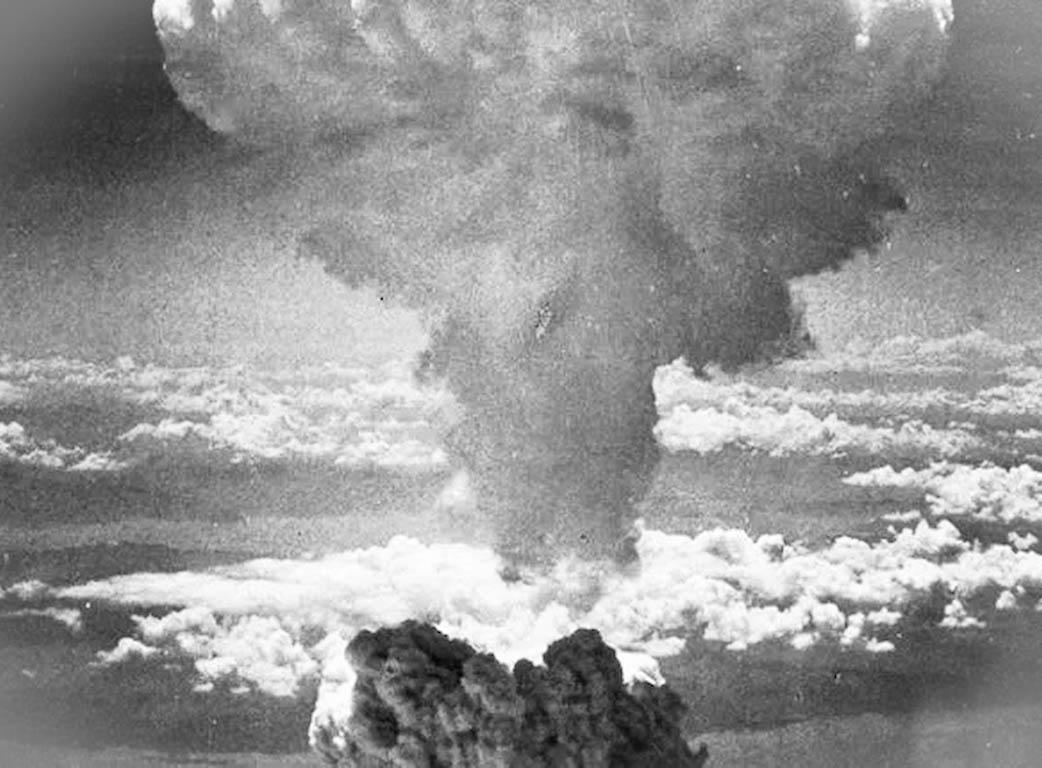

At Potsdam, in July 1945, Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee had both acceded to Truman’s decision to use the Bomb. Around 80,000 died instantly at Hiroshima, with additional tens of thousands dying of radiation.

Hiroshima was not a military centre and lacked major war industries. Those who targeted it ensured that the aiming point should be the centre of the city and not the outskirts, giving the lie to Truman’s diary entry that “The target will be a purely military one”.

Twelve years later, the Catholic philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe authored a pamphlet entitled Mr Truman’s Degree, strongly objecting to Oxford University’s awarding of an honorary degree to the former president. Anscombe sought to defend the traditional Catholic view that intentions (i.e. purposes) are of great importance in judging whether acts are good or evil, and also that there are some choices which are morally ruled out in themselves.

The moral justification put out by Truman and his supporters was that bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki prevented greater loss of life by ending the war quickly. This crude consequentialist reasoning, however, ignores the fact that all our intentions, not just our ultimate intentions, are morally significant.

Anscombe takes it as a moral given that choosing to kill the innocent as a means to your ends is always murder. She writes, “What is required, for the people to be attacked to be non-innocent in the relevant sense, is that they should themselves be engaged in an objectively unjust proceeding which the attacker has the right to make his concern; or – the commonest case – should be unjustly attacking him”, where “what someone is doing” refers to someone’s role as well as what they are doing at a given moment.

The people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were clearly innocent in this sense. And the clear and immediate intention of the bomber pilots and those who ordered the bombing was to obliterate huge numbers of Japanese people as means to their further aim to bring about Japanese surrender.

Even if we park the very real doubts about whether the demand for unconditional surrender was just, and whether the Bomb was needed to achieve it, the question of intention is morally crucial.

Intentions matter: they help form our characters in a special, lasting way. And that includes not only our ultimate intentions but all the means we choose to achieve these. Causing bad side-effects is not always avoidable: we all cause these by many things we do. However, intending certain bad effects can be avoided, and should be avoided. Most of us in fact believe there is a difference between war crimes like targeting of civilians and accepting genuine “collateral damage” – though even this must always be proportionate to a legitimate just war aim.

To intend to kill civilians (or undifferentiated populations) as a means to your end is never going to be morally acceptable. But what do we say about nuclear deterrence in the light of this? If it is never acceptable to choose to bomb innocent people, may we conditionally intend this as part of a deterrence strategy?

Surely not: to have a conditional intention to do something evil is no more acceptable morally than to have a firm intention to do the evil thing whatever happens.

What if nuclear deterrence is simply a bluff and therefore doesn’t involve any morally evil intentions on the part of world leaders? There is no reason to believe world leaders are bluffing – but in any case, as John Finnis and others have pointed out, in order for the system to work at all, a large number of people will have to have actual conditional intentions to carry out the order, albeit as a last resort. So even a leader who is bluffing will be intending that some at least of his subordinates have a conditional intention to perform an intrinsically evil act. US Presidents and UK Prime Ministers are all expected to sign up to a system which requires such intentions.

With the release of the film Oppenheimer and the anniversary next month of the nuclear holocaust perpetrated on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it’s worth recalling authoritative criticism of such actions. The Vatican II document Gaudium et Spes, reaffirming earlier teaching, prominently condemned such acts, stating, “Any act of war aimed indiscriminately at the destruction of entire cities or of extensive areas along with their population is a crime against God and man himself, and merits unequivocal and unhesitating condemnation.”

Focus on intention is focus on the human heart, a focus some prefer to avoid when thinking about ethics. Pope Pius XI, writing at the end of the First World War in Ubi arcano Dei consilio, made the prescient comment, still relevant today: “No one can fail to see that neither to individuals nor to society nor to the people has come true peace after the disastrous war. The fruitful tranquillity which all long for is still wanting. Peace was indeed signed between the belligerents, but it was written in public documents, not in the hearts of men. The spirit of war reigns there still, bringing ever-increasing harm to society.”

See, ‘Oppenheimer’ reminds us of some crucial moral absolutes

Photo. Hiroshima – More than 70 % of the town’s infrastructures were destroyed. © Bettman Archive - Getty Images

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment