"The empire tomb" treasure: mineral resources in Afghanistan

Revista Pandora 20.08.2021 Alberto Prina Cerai Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgWith the collapse of the Afghan government and the power rapid conquest by the Taliban, Afghanistan is back in the hands of Islamic extremism after almost twenty years. Therefore, a chapter of failures and instability closes and another one opens with equally uncertain nuances, both for the fate of the civilian population and for the regional geopolitics. The latest news has brought again this country to the front page.

With the vacuum left by the United States (UN) and the NATO powers, this country, in the heart of Central Asia, would likely return to be a fertile ground for the radical Islam proselytizing, leaving room for other actors such as China, Russia, Turkey, and Iran to manage a territory with very intricate ethnic, religious and political balances.

What could persist is the condition of continuous emergency and crisis that would accompany the 'transition' to power, while would change the sensitivities of the new (geo) political interests no longer declined by Western precepts (State, democracy, human rights, rule of law) that have struggled so hard to take root. It is the umpteenth demonstration of the theory of regime change failure: without stable and strong institutions and efficient infrastructures, Afghanistan could hardly have transformed itself into an economy even if only subtly market. What did go wrong in the country’s reconstruction, and what destiny will it face? Answering these questions is not easy.

However, a common denominator, a common thread between the recent past and the probable future, can be partly found in Afghanistan’s geological heritage. It is interesting to note that many newspapers have brought the attention to an issue now more central than ever: Afghanistan’s mineral resources, abundant in the country in the form of minerals, metals and hydrocarbons. A point of debate that now, with the shared forecast of the Afghan territory’s 'partition' between the incumbent powers, and the US and the European Union’s strong dependence on essential raw materials for the energy and digital transition, becomes suddenly topical.

However, this is a conceptual trap to be debunked for two reasons. As the economic literature on development reminds us, the resources management (more than the mere exploitation) is a decisive factor in the modernization trajectory of a backward country but rich in natural capital. Furthermore, the resources correct governance (taxation on extractive activities, the equitable distribution of income, and the strategy of diversifying government spending) is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for the transformation of an economy requiring stability, certainty of the law, and consequent foreign investments.

The equation between resources and development is therefore not linear. Just as it is misleading to consider the exit from Afghanistan a strategic mistake by the West on the only base of its subsoil richness, especially taking into consideration its significant presence in allied countries (such as Canada and Australia) with a great mining tradition. On the other hand, we should note that, after twenty years of occupation and intense exploration, the security conditions have evidently not been created to attract foreign capital, essential for the emergence of an extractive industrial sector.

Let's take a step back.

In 2010, an internal Pentagon memorandum taken up by US newspapers believed that Afghanistan "could become one of the largest mining centers in the world" and that, thanks to its reserves, it could become the lithium Saudi Arabia. Lithium, now considered above all as a central element for the production of electric batteries, at the time was mainly used in common consumer electronics.

Gen. David H. Petraeus, commander in chief of North American military operations, had declared that under the battlefield between the Special Forces and the Taliban "lay an immense potential", which could have contributed to the country’s economic development, through ripping its political and economic control from the Taliban’s hands.

The need to guarantee the security of a geopolitical context, the promise to the Afghan people’s sovereignty over its resources and the imperative to avoid the strategic resources exploitation by hostile powers were believed to be fundamental vectors for attracting investors and individuals to a land, historically plagued by conflict and political instability.

Interest in mineral resources in Afghanistan, especially for 'rare earths', became explicit with the funding by the US Agency for International Development of a series of geological surveys and studies undertaken by the US Geological Survey (USGS) in collaboration with the Afghan counterpart (AGS). It was just the year in which China, then a monopolist in extraction, blocked the export of precious metals to Japan following a diplomatic dispute over the Senkaku Islands.

The surveys showed the presence of 1.4 million tons of rare earths - the Khanneshin deposit in Helmand province, at the time a stronghold of the Taliban, is considered the largest deposit in the world. Not only, but also of 60 million tons of copper, 2.2 billion tons of iron, precious gems and other non-ferrous metals, with an estimated value of $ 1-3 trillion, according to the most recent estimates were found. This was not a discovery, but a confirmation: a series of previous papers and analyses carried out by the Soviet Union between the 1970s and 1980s had already estimated the Afghan mining potential, leading the Soviets to spend billions of dollars to build the necessary mining infrastructure.

However, with the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989, the projects were abandoned. North American and British colleagues restarted them in 2003 at least on paper. Besides, it was not just about minerals. According to an Afghan report, also taken up by the USGS, Afghanistan could count on oil reserves of 1.6 billion barrels, 16 trillion cubic meters of natural gas and another 500 million barrels of liquefied gas, while in the provinces of Tajik Basin and Amu Darya Basin would exist other undiscovered deposits.

Shortly after the rediscovery, in 2014, an article in Scientific American read: "[...] the vast deposits of rare earths and critical minerals found in Afghanistan by North American geologists under military cover could solve the world shortage and free the country from opium dependence and of the Taliban’s control.”

[...] In addition to the strategic importance of these elements - used in many of the US military equipment in their Afghanistan’s operations and that remained largely in the hands of the Chinese rival-, the 'rare earths' had also become a potential tool to exercise an even more effective political control when the military occupation did not give the desired results to state-building and post-conflict reconstruction.

The presence of the North American military contingent therefore became essential to support the private sector’s activities, which, in turn, would have required, in a reciprocal reinforcement mechanism, the US military presence for an indefinite period, necessary pending autonomous local government institutions. Strong collaboration was also needed between the Pentagon, AES and any interested international companies.

The task of fostering the birth of an industry for the exploitation of Afghanistan’s mineral resources was the responsibility of the Defense Department's Task Force for Business and Stability Operations. In the mining sector, information on the mineralogical configuration of the deposit - and therefore its actual cost-effectiveness (the difference between resource and reserve) - is crucial for the investor. "Working with the Afghan Geological Survey for the aerial geophysical exploration program," said the Task Force's director of mineral resource development in Afghanistan, "is an important step in preparing the Afghan government to conduct its own mining exploration efforts. The goal of this training is to allow it to provide the best possible information to international investors."

From 2012 on, the investors’ pressure to maintain military control has increased dramatically, mainly due to the fear that other actors - China, Russia and India - could capitalize on the area stabilization efforts by the West. Even the Afghan population saw the development of this sector as a potential valve for development and for liberation both from the Taliban’s illicit trade and from international aid. In 2014, in a letter addressed to British Prime Minister David Cameron and signed by forty organizations, the director of Integrity Watch Afghanistan, Ikram Afzali, declared: “We want to develop our natural resources, but from a strength and pride position, neither loosening our standards nor ignoring abuses”. It is clear that the reference was to foreign interference in the management of the fields, with a claim under the banner of sovereignty and 'resources nationalism' [...].

At the same time, it was a not so simple issue to realize. Although committed until the fall of his government to transform Afghanistan's mineral resources into economic wealth, former Afghan president Ashraf Ghani, now in exile, with a career as an economist at the World Bank, in 2020 believed that the country, already torn by conflict and structurally fragile, risked running into the 'curse of resources', especially in the absence of a coordinated development strategy by the ally forces, local government, and a profound private sector reform.

In the fall of 2017, President Donald Trump and Ghani met in New York to discuss prospects for exploiting mineral resources in Afghanistan. A White House statement followed the meeting. It stated that the mining initiatives "would help American companies develop critical materials for national security while enriching the Afghanistan economy, creating new working jobs in both countries and therefore contributed to lightening the costs of US’s assistance by making the Afghans more autonomous”.

Despite the intentions, the difficult political situation and the instability due to the perennial conflict did not allow to lay the foundations for the flourishing of economic activities. According to two reports published respectively in 2017 and 2018 by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), the US has spent hundreds of millions of dollars since 2009, but this has happened in the absence of a true unified strategy in order to facilitate the mining industry. Moreover, with the emergence of commercial fresh outbreak with the People's Republic of China and considering the strategic dependence on some critical materials, the US has started a new redefinition of its mining policy, both in the domestic sector and in the field of international partnerships. All the while neglecting - perhaps voluntarily - the mineral wealth under the semi-official control of the Kabul government. In a United Nations Development Program report of March 2020, the scenario described was bleak. "Currently, it said, mineral resources contribute very little to the economy and society", mainly "because most of them remains underground, but also because most of the mining is illegal or informal", with more than 160 artisanal mines.

Among the most promising sites there is the Mes Ayak’s one, rich in copper - a field of 11.5 million tons, with a potential value of 100 billion dollars at current prices. The Chinese Metallurgical Group and Jiangxi Copper acquired its license for 3 billion dollars, as reported by the Italian Il Sole 24 Ore. It lies surrounded by the priceless cultural and archaeological heritage. The other one is that of Hajigak, rich in iron, whose contract has been suspended due to the area insecurity and for the lack of transport. "If the country wants to unlock the potential of its mineral wealth - the report continues - the government and other stakeholders will necessarily have to strengthen the management of resources and ensure peace and security".

According to estimates, only 2% of government revenues (42 million dollars) come from the mining sector, while in 2017 Kabul could have raised about 123 million dollars in the form of royalties and export taxes.

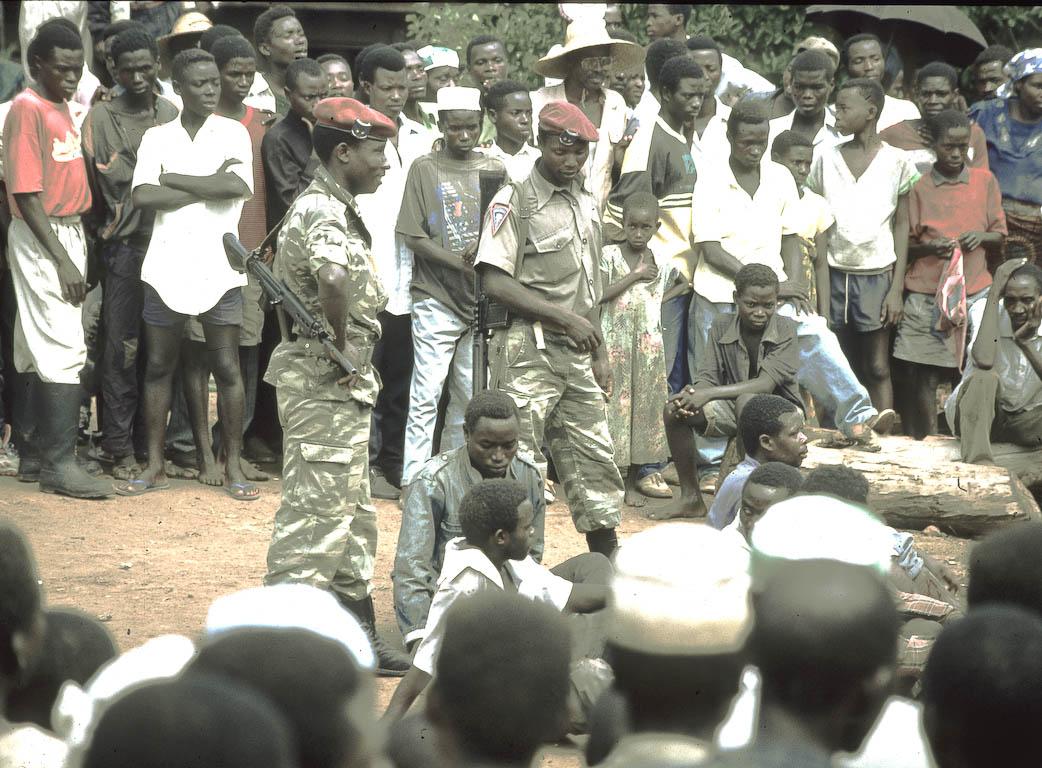

In fact, the failure of government authorities to control the extraction of mineral resources in Afghanistan has stimulated the interest of the rebels (especially the Taliban), who saw the opportunity both to obtain resources to finance the conflict and to delegitimize the state, thus contributing to the increase of chaos and violence. [...]

A more widespread control of the extraction sites by the Taliban forces will imply greater risks of illegal exploitation, social control and, finally, potential environmental damage due to a lack of rules and governance in the sector, as well as significantly replenishing the Taliban’s coffers. According to a 2018 Global Witness report, "the revenues flowing into criminal groups, 'warlords' and the Taliban from the small area of Badakhshan province alone compete with those declared by the central government from the entire sector". In fact, the mineral resources - especially the most precious, such as gems in particular lapis lazuli - are the second largest source of funding (about $ 300 million) after opium and heroin of Afghan rebel groups. In late January 2021, Mohammad Haroon Chajhansuri, Minister of Mines and Oil, frankly denounced to the press, "the Taliban currently controls 750 mining sites, using the revenues against the government".

"The Taliban are now sitting on some of the most important strategic minerals in the world," said Rod Schoonover, head of the Ecological Security program of the Council on Strategic Risks, a Washington think tank. But, it remains to be understood "whether they can or will use" these resources as the basis of the future economy. It is evident that the Taliban or any rebel group does not possess the sufficient capital and know-how to accomplish what two superpowers like the Soviet Union and the United States, in different historical periods but united by similar scenarios of instability, have failed to bring about.

However, the sudden retreat of US military forces has left a political vacuum that China - considering the financial and industrial assets it owns in the mining sector - could exploit. The Week magazine reported on a meeting between Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and a Taliban delegation, which ended with the agreement for Beijing’s greater role in the "future reconstruction and economic development of the region", perhaps including the country in the dense web of investments called the Belt and Road Initiative. China, between 2007 and 2008, had already secured a license for the Mes Ayak copper mine and had started some infrastructure projects, without however completing them. The rare earth and lithium deposits remain of potential interest […].

China currently owns and trades in abundance this type of resources - controlling the highest value-added stages of the value chain - but looking ahead, the exploitation of Afghan fields could reduce the environmental degradation associated with the extraction and domestic processing of these materials.

An agreement between the Taliban and the Chinese government could be reached without too many obstacles from the point of view of governance - with great opacity with respect to issues related to human, social and environmental rights. However, it would not be so immediate, given the almost total absence of infrastructures, electricity and energy networks and water pipes necessary for carrying out extractive activities on an industrial scale.

Even on the commercial level, question marks would remain. The growing financial (think of the so-called ESG - Environment, Social, and Governance standards, now dominant in the financial sector) and regulatory monitoring of global companies involved in the sector, could hinder the scope of the activities of state-owned enterprises operating in Afghanistan in collaboration with the Taliban.

On 10 January 2021, the 2017/821 Conflict Affected and High Risk Areas Regulation entered into force, with which the EU monitors that the tantalum, tungsten, gold and tin imports do not come from areas affected by war and that they are traded online with European policies relating to the prevention of armed conflicts and development. A similar argument applies to the United States.

The restrictions in place, especially under the umbrella of the 1502 Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 section, require North American companies not so much to stop supplies from listed regions, but rather to submit a due diligence report, to verify that their commercial activity is neither a source of financing for armed groups nor that it leads to human rights abuses. The Taliban are not designated as a 'Foreign Terroristic Organization', but are placed on a special list by the Treasury Department. Considering the risks and potential developments, it is desirable that Afghanistan's mineral resources should in the future be subjected to severe scrutiny would illegal activities emerge.

In conclusion, considering the wide availability of resources in regions characterized by higher development and stability indices, it is clear that the private sector and the most prudent investors will keep far away from Afghan territory, in the context of an even more explosive situation. Internal competition between the different factions could make investments by entities controlled by the governments of China and Russia not so obvious. [...] It remains quite unlikely that the Central Asian crossroads, considered the most recent history, comes to be the solution to calm the explosion in demand for minerals and metals required by the global market in the coming decades or to take on a strategic position in the sector, as supposed by the media. [...]

The ‘rare metal war’ hotspots on other geographic context have economic potential more promising, or are in the process of consolidating to achieve it. There remains the bitter awareness, as sanctioned by the latest SIGAR report that the mining sector has failed to act as a vehicle for economic growth and a source of sustainable revenue for the Afghan government. A lost opportunity in the context of the difficult reconstruction of the country, compared to what were the promises of a free and prosperous future during these twenty years to the Afghan people.

See Il tesoro nella “tomba degli imperi”: le risorse minerarie in Afghanistan.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment