2025. Ordinary Jubilee Year

Butembo 20.12.2024 Jpic-jp.org Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgPope Francis has announced that 2025 will be an Ordinary Jubilee Year. Following tradition, he published a bull with the title: ‘Hope does not disappoint’.

The celebration of a Jubilee Year in the Catholic Church was proclaimed for the first time in 1300 by Pope Boniface VIII, who established the deadline every hundred years. At the time when the Popes resided in Avignon (1305-1377), Pope Clement VII agreed to the pressing requests to convoke the Jubilee in 1350 rather than in 1400, and set the deadline every 50 years. Finally, Paul II, in 1470, established that in future the Jubilee would take place every 25 years.

These ‘ordinary’ Jubilee years were interspersed with a number of ‘extraordinary’ Jubilees. Pope Pius XI proclaimed the year 1933 the Extraordinary Jubilee of the Redemption to celebrate the 1900th anniversary of the Passion, Death and Resurrection of Christ, and Pope John Paul II proclaimed a second Extraordinary Jubilee of the Redemption fifty years later. With the Apostolic Letter Tertio Millenio Adveniente he also proclaimed the year 2000 as an extraordinary Great Jubilee for the 2nd millennium of Christ's birth. Finally, Pope Francis called for an Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy from 8 December 2015 (Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception) to 20 November 2016 (Feast of Christ the King).

What is the Jubilee?

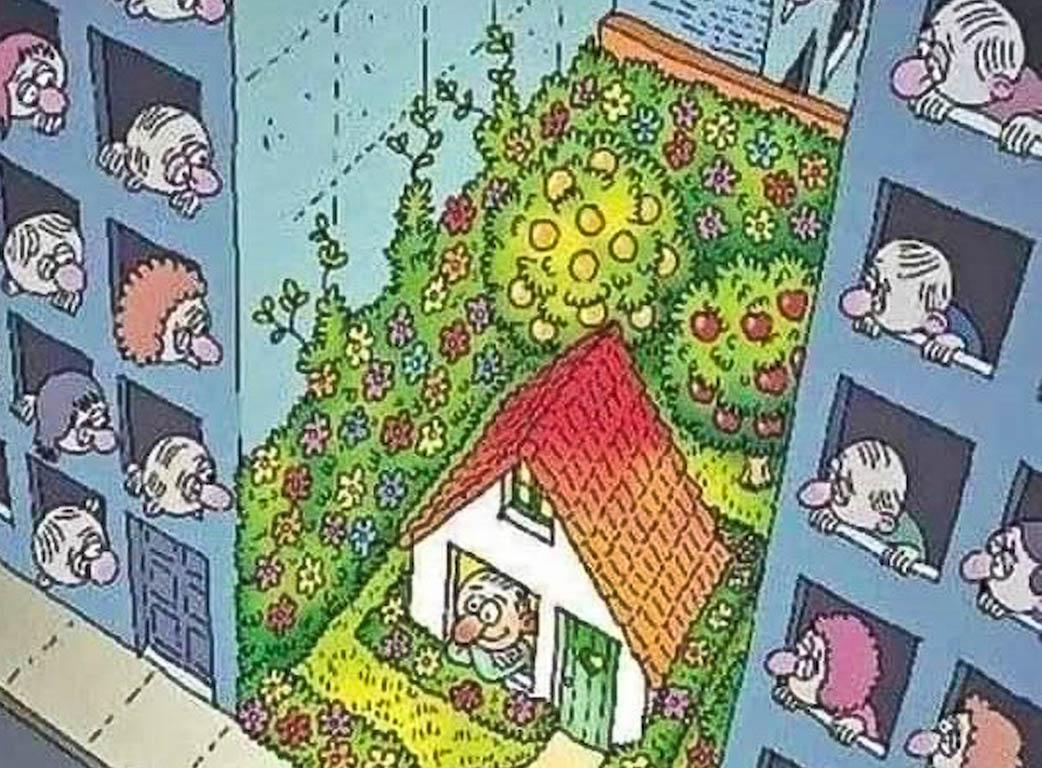

The origins of the Jubilee go back to the Old Testament, when the Law of Moses commanded the Hebrew people: ‘You shall declare holy every fiftieth year’. The purpose of the Jubilee was ‘freedom’ (deror in Hebrew), because this year, the Law said, ‘you shall proclaim freedom in the land for all its inhabitants. It will be a jubilee for you’.

It was a year of liberation for slaves and servants, symbolising justice and equality; a year of restoration, as the land sold was returned to its original owners, re-establishing economic and social equity; a year of sanctification, highlighting the recognition of God's sovereignty: to Him belongs the land of which men are only stewards. In this way, the earth regained its dignity and was put to rest: ‘You shall not sow, you shall not reap the ears that have not been sheathed, you shall not gather the vines that have grown freely’.

In short, the aim was to restore social balance, promote freedom and remind people of their dependence on God: it was an experience of forgiveness, social justice, equality, rest and spiritual renewal. The Jubilee was a proclamation of God's desire for freedom, dignity and fairness among his people. The ram's horn, ‘yôbel’ in Hebrew, heralded this year, hence the word ‘Jubilee’.

Pope Francis, in proclaiming 2025 the Jubilee Year, refers to the Mosaic Law taken up by the prophet Isaiah 61:1-2: ‘The Lord has sent me to bring good news to the lowly, to heal the broken hearted, to proclaim release to captives and freedom to prisoners, to proclaim a year of blessings from the Lord’. These are the words that Jesus made his own at the beginning of his ministry.

The Jubilee is therefore a year of grace that Pope Francis this time puts under the sign of hope, which ‘calls for acts of clemency and liberation’: the Church must become the interpreter of these requests ‘to courageously demand dignified conditions for those who are imprisoned, respect for human rights and above all the abolition of the death penalty’.

The Jubilee is also a time when the Church offers its faithful what is known as a ‘plenary indulgence’ for themselves and the dead, i.e. the remission of temporal punishments and the consequences of sins. Christians receive it through the sacraments and through works of charity and justice: reconciliation between enemies, conversion and solidarity, hope lived out in joy and fraternal peace.

The belief in indulgence (indulgere in Latin) dates back to the practice of the primitive Church: Christians guilty of serious sins had to perform long public penances that the bishop or confessor could reduce by being indulgent, out of kindness, by granting total or partial remission of the penalty. The idea of indulgence was formalised in the Middle Ages, in connection with the belief in purgatory. The Church has always taught that sin forgiven in the sacrament of confession leaves after-effects, ‘traces’ as the Pope says in his bull, and ‘entails consequences’ in human and social life, the so-called temporal penalties to be expiated. Indulgence makes it possible to reduce or cancel these traces, consequences and penalties.

A controversial practice.

The idea of indulgences emerged from the 11th century onwards, but only took clear form with the proclamation of the First Crusade in 1095, when Pope Urban II promised a plenary indulgence under certain conditions to crusaders who set out for the Holy Land. In the 13th and 14th centuries, this practice became more structured and indulgences became more accessible, often linked to pilgrimages, works of charity and donations for Church projects. This opened the door to the sale of indulgences. Pope Leo X - at the beginning of the 16th century - took advantage of this by launching a vast campaign to finance the construction of St Peter's Basilica in Rome and by making plenary indulgences, especially for the dead, a means of raising funds. The Dominican monk Johann Tetzel codified the practice: ‘As soon as the money hits the till, a soul flies out of purgatory.’

Criticism poured in, culminating in Martin Luther's famous 95 Theses, posted in Wittenberg Castle Church (1517), which sparked off the Protestant Reformation. Luther rightly saw the indulgences as a commodification of the faith, a sign of the Church’s corruption in contradiction with the Gospel: salvation, the gift of divine grace, cannot be bought; the faithful are turned away from true repentance and works of charity; the Pope has no authority neither over souls nor over purgatory. The Council of Trent (1545-1563) reaffirmed the validity of indulgences, condemned their abuse and introduced strict regulations.

Today, the Catholic Church retains indulgences, including plenary ones, under certain conditions: confession, communion, prayer for the Pope, rejection of any attachment to sin and, as Pope Francis reminds us, a return to works of mercy in response to the ‘ancient call that comes from the Word of God and that endures with all its sapiential value: ‘You shall declare this year holy and proclaim the emancipation of all the inhabitants of the land (Lev 25:10).’ The Jubilee is intended to be a time of liberation, to re-establish justice and equality; a time of restoration, to ensure economic and social equity; a time of sanctification, to affirm God's sovereignty and respect for creation.

It sometimes happens that ideological and religious conflicts with political implications - in Luther's time it was the opposition of the German princes to the Emperor Charles V, an ally of the Pope - in the effort to re-establish certain values end up nullifying others.

For the Catholic faith, thoughts, words and actions that are contrary to morality are an offence against God because they are faults against humanity and creation. At the heart of indulgence is the desire to reduce the negative consequences of these sins, which have an impact on private, public and social life, and - thanks to the sacrament, prayer and works of mercy - to restore harmony between individuals, between peoples, between humanity and creation once - or at the same time - the offence against God is been by the sacrament.

Luther was right: the Church in its greed was trying to manipulate this reparation. However, reducing indulgence, and therefore sin, to a purely spiritual sphere had the unfortunate consequence, among others, that Catholics lost interest in the political sphere, in ‘the city of men’, as St Augustine called it. On the contrary, the doctrine of indulgence, properly understood, could have awakened the awareness of corporate responsibility, something that only now is perceived.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment