Every human being lives by hope

Il coraggio e la paura 19.04.2025 Vito Mancuso Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgPope Francis put “Pilgrims of Hope” as the slogan of the Jubilee year; for Catholics, hope is a theological virtue, giving the false impression that it is attributable only to Christians; in reality every human being “has one and lives by it”. This is the point of view of a philosopher.

Every human being has one and lives by it, given that we are our desires and that the sum total of desires constitutes the goal towards which we strive, which can be called hope; what makes this hope a virtue, however, is hope in the good, in the possibility of real change in favour of greater justice. The value of a human being and his thinking is also measured here.

It is not by chance that Kant placed hope among the three objects par excellence of thought, along with knowledge and ethics, as we read in a passage from the Critique of Pure Reason where he presents the three fundamental questions that every human being should ask himself: "Every interest of my reason (both the speculative and the practical) is concentrated in the following three questions: 1-. What can I know? 2-. What should I do? 3-. What can I hope for?" The use of the first person singular signals that what is at stake here is not academic disquisitions, but concrete existence here and now in search of a meaning for which, and to live by. Kant later reformulated the thought as follows: "The field of philosophy can be traced back to the following problems: 1-. What can I know? 2-. What must I do? 3-. What can I hope for? 4-. What is man? The first question is answered by metaphysics, the second by morality, the third by religion, and the fourth by anthropology. But, in the end, all this matter could be ascribed to anthropology, because the first three questions relate to the fourth.”

It is therefore ultimately a matter of anthropology, but not as an academic discipline, but as an existential question that the borderline situation intuits here and now for everyone's conscience: you, what human being are you? Our identity is not static but dynamic, that is, determined by the nebula of needs-desires-aspirations that call forth our inner chaos and give it direction and form. Our truest identity is given by our hope. So when does a human being change?

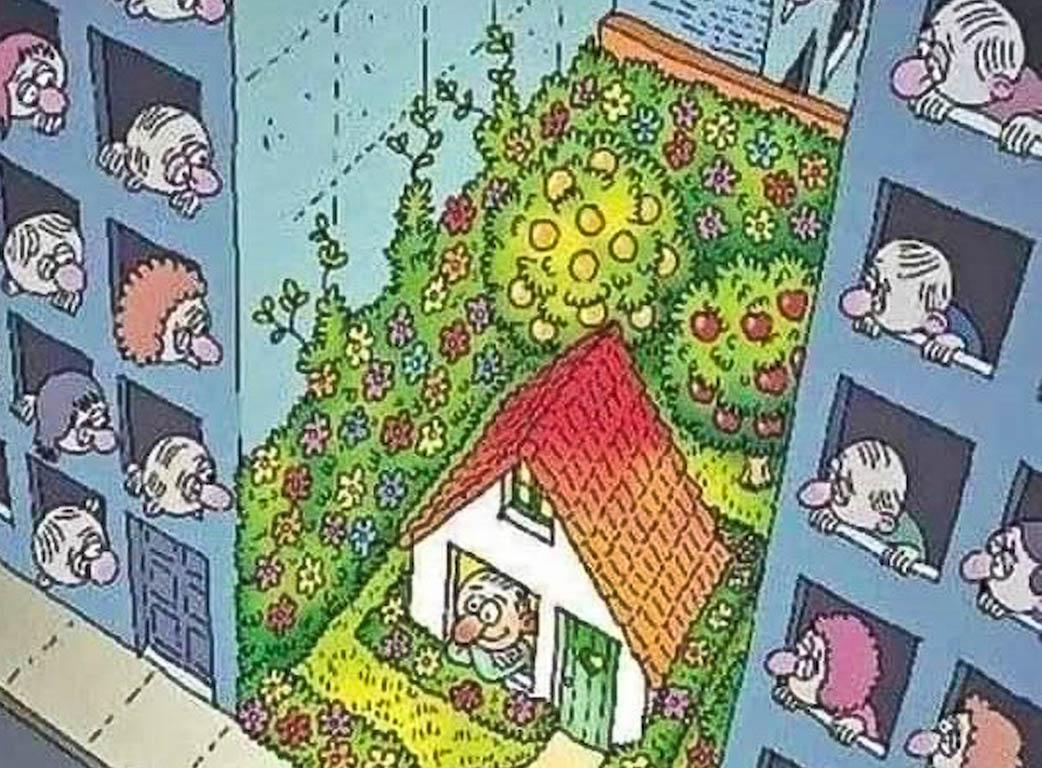

A human being changes when his desires change, the sum of which is called hope, which, instead of tending towards needs, rise and become aspirations, so that, instead of feeling the irrepressible desire for the umpteenth pair of shoes or a bag or a shirt, or a position or recognition or applause, he begins to feel the desire for fewer shoes, fewer bags, fewer shirts, fewer positions, less recognition, less applause, less everything, just real things, please, just real things and real people, please: real music, real pages, real friends, real relationships. Real life.

I read somewhere that according to Isidore of Seville, a sixth-century scholar and expert in etymologies, the word hope, in Latin spes, comes from pes, foot; well-founded or not, the etymology is suggestive: hope is what makes one walk through life. Without hope, one does not walk. A famous page from Aeschylus of Prometheus, the titan who stole fire from the gods to give it to men, confirms this. While he was chained on a mountain in Caucasus by order of Zeus, with an eagle that during the day eats his liver, which then grows back at night, a coryphaea asks him the reason for his condition and Prometheus answers her that he was punished for taking pity on human beings: “Men always had, fixed, before their eyes death: I made that look cease.” The coryphaea asks him: “And what remedy have you found for this evil?” Answer: “I made blind hopes dwell within them.” Only at this point does Prometheus add: “And then I procured fire for them.”

Before giving men fire, Prometheus gave them hope, which is called blind not because it is fatuous, but by definition: hope in fact does not see how it will end. It is blind, yet it is strong and gives strength, to the point that the very use of fire requires its presence because of the confidence that the work will be fruitful.

Hope has always been connected to the essence of humanity, as taught by Aeschylus, Kant and the spiritual traditions. Hope and fire, trust and technology, wisdom and science, must once again be closely connected in society and, even before that, in the existence of each of us.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment