Six key points about the UN before its 75th anniversary (Part One)

The Conversation 25.06.2020 Pedro Rodríguez Translated by: Jpic.jp.orgThe second secretary general of the United Nations (UN), the Swedish: Dag Hammarskjöld, gives one of the best definitions of the organization since it started 75 years ago in San Francisco: “It has been said that the United Nations was not created in order to bring the society to heaven, but in order to save it from hell.” (Translated from Spanish by Alissa D’Vale)

On June 26, 1945, when the Charter of the UN was signed at the San Francisco Conference, it didn’t take much gruesome imagination to think of the worst in human nature. The tragedy of the Second World War was able to open, almost completely, the gates of hell: genocide, weapons of mass destruction, systematic violations of human rights and a confirmation of the indiscriminate cost of modern warfare.

In its 75th year of existence, the UN continues to sit between heaven and hell. Its anniversary coincides with enormous global problems within a changing international order. In fact, it could be argued that the coronavirus pandemic has managed to reopen the gates of hell to the point that the UN secretary general, Antonio Guterres, has warned that COVID-19 represents the greatest threat to humanity since World War II.

For a long time, renegades of the international liberal order have insisted on questioning the relevance and viability of the UN, regardless of the fact that it was the result of an exceptional historical moment in which the United States and its allies tried to learn and rectify the traumatic lessons accumulated during the interwar period.

Among other things, that international system built at San Francisco and at Bretton Woods represents the will to not stumble twice on the same stones of history; with a commendable effort in the search for collective security, stability of the international financial system, promotion of free trade, the promotion of solidarity between nations and the rehabilitation of the defeated.

1-. Underestimated importance

The relevance of the UN is often questioned, especially when the most powerful countries perceive the organization as an obstacle to their own interests. And in fact, the pressures for comprehensive reform have multiplied by taking advantage of all types of scandals. Currently, the lack of resources and the confrontation between the United States and China coexist with the frustration of developing countries and the growing suspicions that the world may be changing for the worse.

Faced with this huge memorial of grievances and pending issues, authors such as the historian Paul Kennedy have argued that the UN should now be more valid than ever.

For Professor Kennedy, the future projection of the UN would connect with its most positive records, with achievements that range from saving millions of lives to raising health and education standards around the world.

In practice, there are multiple United Nations, as Kennedy insists:

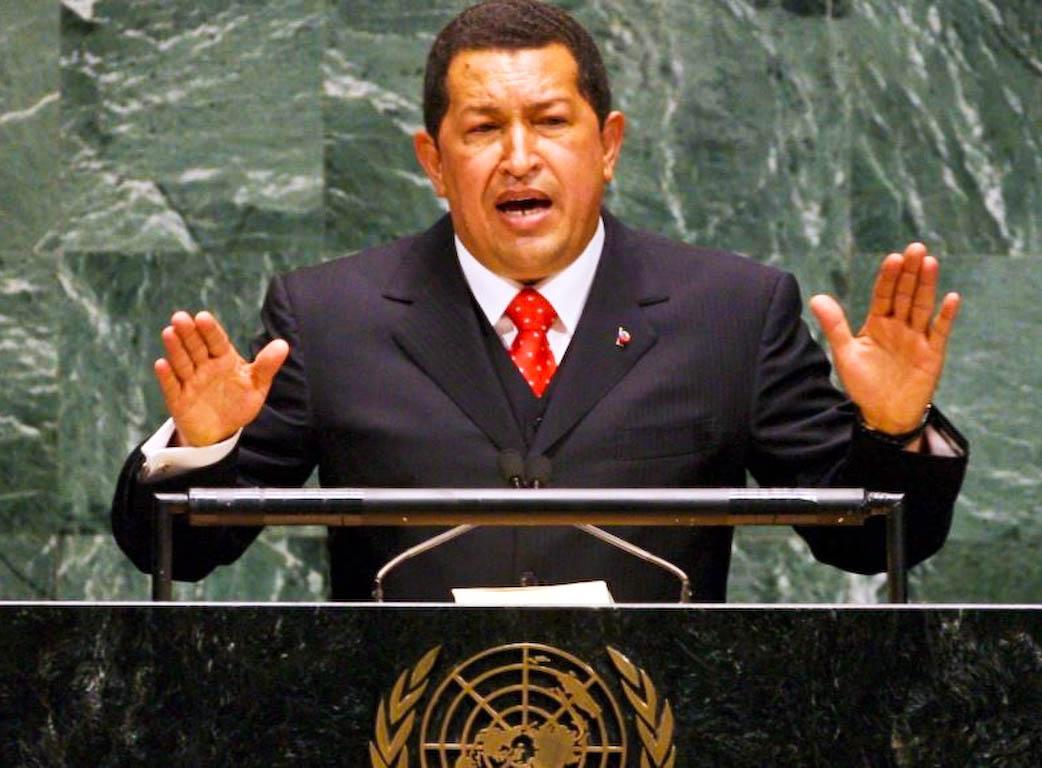

- There is the UN of general secretaries, diplomatic celebrities with the opportunity to take advantage of that particular status to work as neutral mediators in conflict resolution.

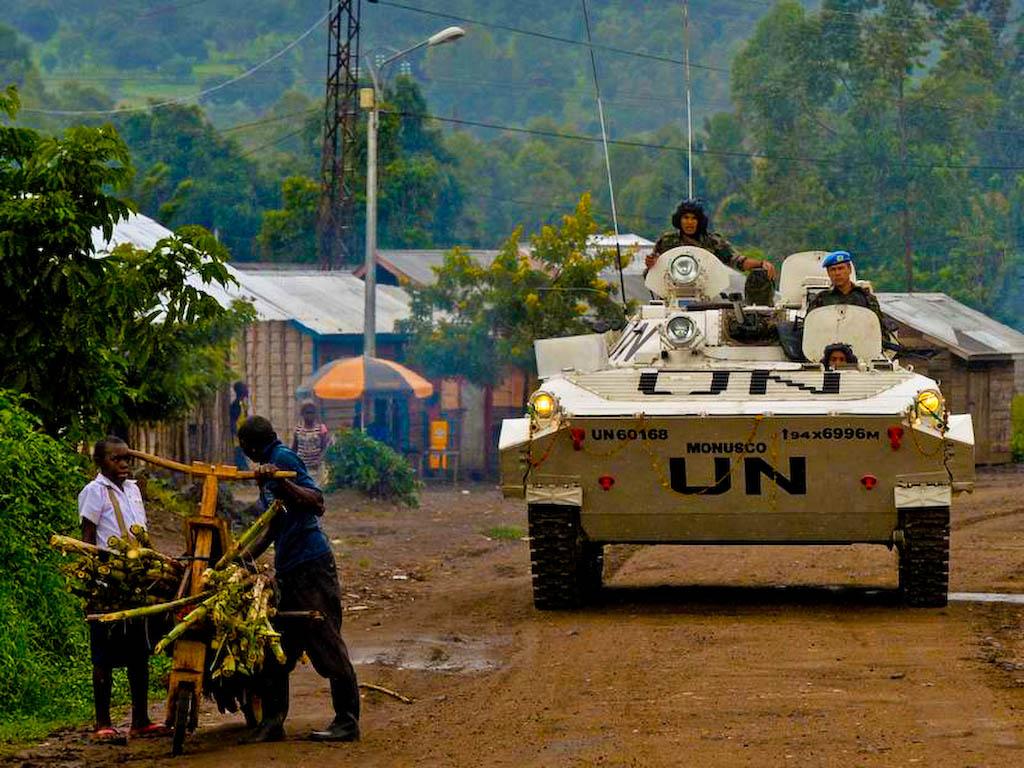

- The UN involved in peace operations, an endeavor that is both costly and complicated, but that has ended up becoming an indispensable tool for world security.

- There is also the UN of soft power, increasingly relevant to advance its agenda. And we must not forget that the UN functions as a simple reflection of its member states, despite the democratic mythologies that insist that the organization should serve as a true global parliament or even act as a world government.

On the occasion of the 70th anniversary celebrated in 2015, the UN adopted one of its most important commitments with the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. It is a guide with a 15-year period, aimed at eradicating poverty and preserving a planet subjected to global crises as threatening as the coronavirus pandemic itself. The document, which does not contain any contractual obligation, is formulated from 17 decisive goals and 169 objectives.

These sustainable development goals include the eradication of extreme poverty by 2030; free access to education up to high school; the fight against discrimination and violence against women; access to clean and affordable energy; economic development; the elimination of inequality that affects 75% of the world’s population; and the promotion of strong democratic institutions.

Against these ambitious goals, the UN estimates that corruption, the abuse of public resources and tax evasion cost the world an annual bill of more than 1.3 billion dollars.

2-. Three founding principles

The founding of the UN – with the 51 countries initially committed to the San Francisco Charter – was based on three founding principles similar to those of the League of Nations, according to Professor Karen Mingst. These principles have not stopped being questioned or even altered with the passage of time and changing geopolitical realities:

– The UN is based on the notion of sovereign equality of its member states, consistent with the tradition of the Westphalian system generated after the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648).

Each member state, regardless of its size or importance, is legally the equivalent of any other state. This equality justifies each state having one vote in the UN General Assembly.

However, real inequality between states is recognized through veto power in the Security Council. A privilege awarded to its five permanent members, the winners of World War II: the United States, Russia (after the collapse of the USSR in 1992), France, Great Britain and the People's Republic of China (position held until 1971 by Taiwan).

This inequality is also recognized in the special role reserved for the wealthiest nations within the organization’s budget process; like the heavier weight of vote in institutions such as the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund.

– The second principle in which the UN is based is that its jurisdiction is limited to international problems. In line with the Westphalian system, the UN Charter does not authorize it to intervene “in matters that essentially belong to the domestic jurisdiction of each State.”

However, this rigid distinction between the domestic and the international has been weakening, causing an erosion of sovereignty of its member states.

Global communications, economic interdependence, international human rights, control of the electoral processes, and regulation of the environment are all areas that go beyond domestic jurisdiction and involve implicit transfers of national sovereignty.

War itself, increasingly embodied in civil conflicts, theoretically is not part of the UN’s portfolio of responsibilities. But in the face of human rights violations, refugee exoduses, arms trafficking and other cross-border aspects of a war conflict, the UN is perceived as the most appropriate organization to take action. A perception that has resulted in the development of humanitarian interventions by the organization even without the consent of the affected countries.

– The third principle is that the UN is designed primarily to maintain international peace and security. This means a commitment on the part of their States to refrain from the threat or use of force. Instead, they must use peaceful means to settle their disputes, in accordance with the framework built through the Hague conferences, and must support the agreed measures and sanctions.

The foundation of both the League of Nations and the United Nations is based on the security vision of the realist theory: protection of national territory. However, the UN is increasingly faced with demands for action that support a much broader definition of security. For example, the so-called Human Security and the enormous problems posed by the current proliferation of failed states.

See the original article: Seis claves sobre la ONU ante su 75 aniversario. See more here: Born to prevent war, UN at 75 faces a deeply polarized world

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment