ICJ and ICC: what are they?

Butembo 15.06.2024 Jpic-jp.org Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgIn these months of war between Israel and Hamas, there is often talk of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Court (ICC), with overlapping functions and decisions that can lead to confusion, when in fact the two courts should not be confused.

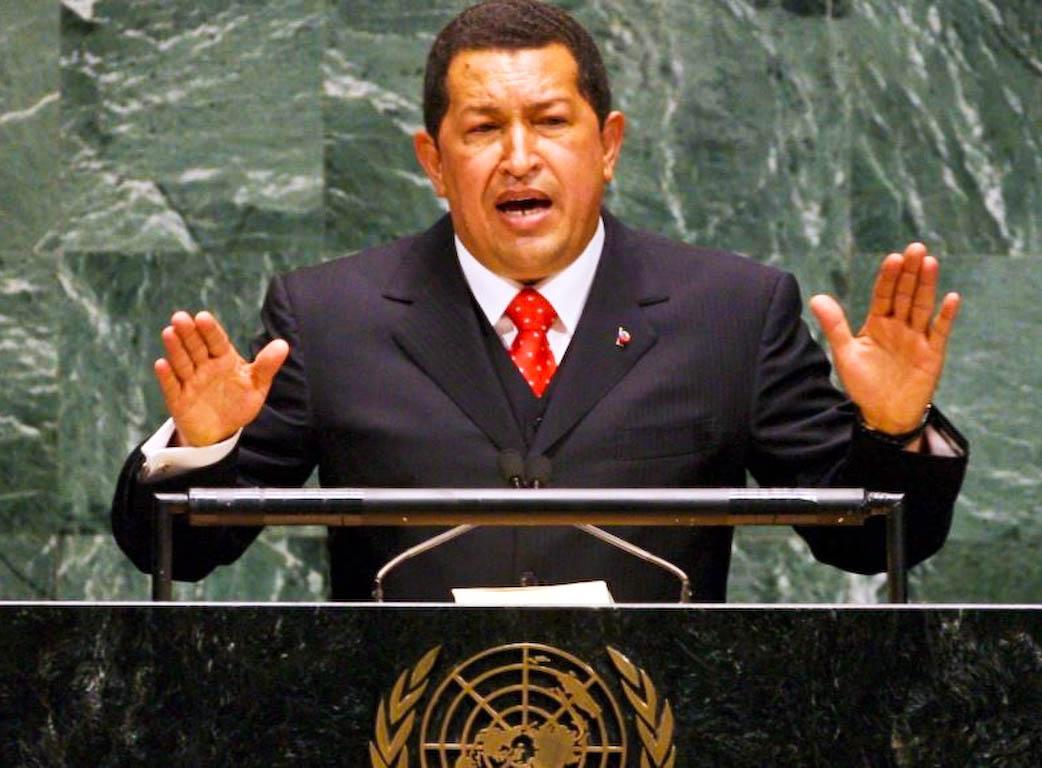

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is the principal judicial organ of the United Nations (UN). It was established in June 1945 by the Charter of the United Nations and began work in April 1946.

The seat of the Court is at the Peace Palace in The Hague (Netherlands). Of the six principal organs of the United Nations, it is the only one not located in New York (United States of America).

The Court’s role is to settle, in accordance with international law, legal disputes submitted to it by States and to give advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by authorized United Nations organs and specialized agencies.

The Court is composed of 15 judges, who are elected for terms of office of nine years by the United Nations General Assembly and the Security Council. A Registry, its administrative organ, assists it. Its official languages are English and French.

These organs vote simultaneously but separately. In order to be elected, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of the votes in both bodies. This sometimes makes it necessary for a number of rounds of voting to be held.

In order to ensure a degree of continuity, one third of the Court is elected every three years. Judges are eligible for re-election. Should a judge die or resign during his or her term of office, a special election is held as soon as possible to choose a judge to fill the unexpired part of the term.

Elections are held in New York (United States of America) during the annual autumn session of the General Assembly. The judges elected at a triennial election commence their term of office on 6 February of the following year.

All States parties to the Statute of the Court have the right to propose candidates. However, they are elected by a mechanism so that the Court does not include more than one national of the same state; the judges as a whole represent the major forms of civilisation and legal systems of the world; and, once elected, the members of the Court do not feel that they are the delegates of either their government or the government of any other state.

Unlike most other organs of international organizations, the Court is not composed of representatives of governments. Members of the Court are independent judges whose first task, before taking up their duties, is to make a solemn declaration in open court that they will exercise their powers impartially and conscientiously.

However, when engaged in the business of the Court, the Members of the Court enjoy privileges and immunities comparable with those of the head of a diplomatic mission. They receive a basic annual salary (which in 2023 amounted to $191,263), a post adjustment and a special supplementary allowance of $25,000 for the President.

The International Criminal Court (ICC), for its part, investigates and, where warranted, tries individuals charged with the gravest crimes of concern to the international community: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and the crime of aggression. As a court of last resort, it seeks to complement, not replace, national Courts. The Court's action also has a preventive and deterrent dimension: the aim is to hold individuals accountable, whether they are civilian or military authorities.

The international treaty founding the International Criminal Court is the Rome Statute. It was adopted at a conference of representatives of the member states of the United Nations, known as the Rome Conference, which took place from 15 June to 17 July 1998 in Rome, Italy. It came into force on 1 July 2002, after being ratified by 60 States: the International Criminal Court was then officially created. As the Court's jurisdiction is not retroactive, it can only deal with crimes committed on or after that date.

The Court's official headquarters are in The Hague, in the Netherlands. As of February 2024, 124 of the 193 UN member states have ratified the Rome Statute and accepted the jurisdiction of the ICC (including all EU states). Thirty-two States, including Russia and the United States, have signed but not ratified the Rome Statute. Some, including China and India, have not signed the Statute.

The ICC may exercise its jurisdiction if the accused person is a national of a State, or if the alleged crime is committed on the territory of a State that has ratified the Statute, or if the case is referred to it by the UN Security Council. The Court can only exercise its jurisdiction when national courts are unwilling or unable to try international crimes (principle of complementarity). In other words, the Court only intervenes when national courts are unwilling or unable to do so.

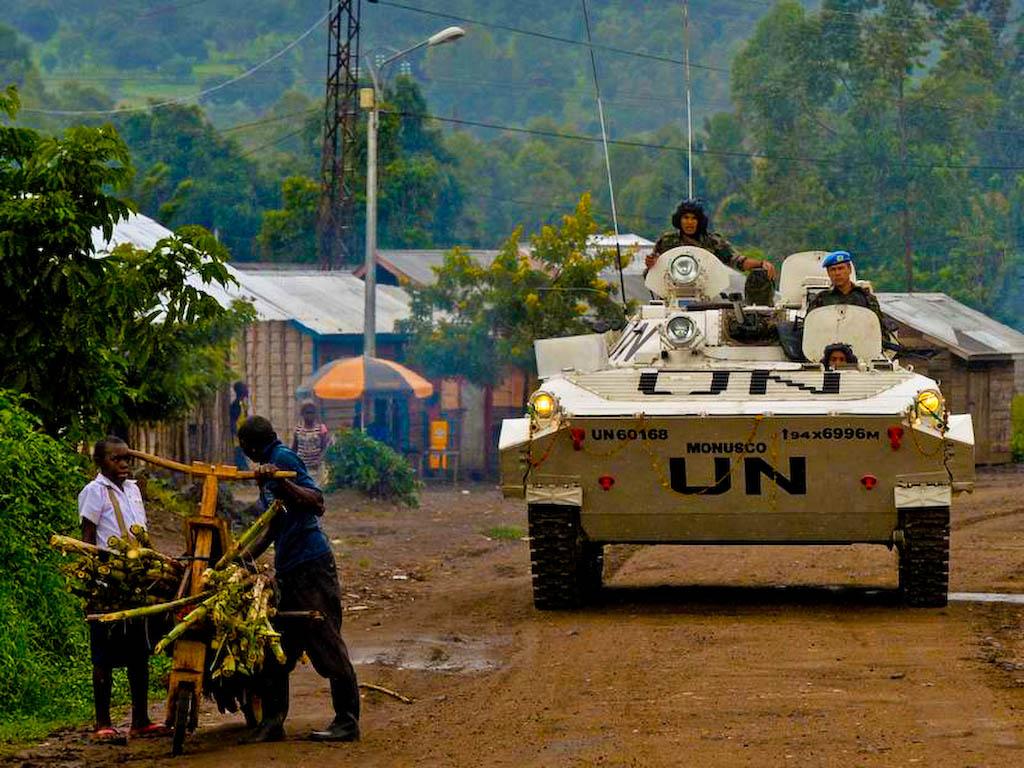

By the end of 2022, the Court had opened investigations in seventeen situations: Uganda (2004), Democratic Republic of Congo (2004), Sudan (2005), Central African Republic I (2007), Kenya (2010), Libya (2011), Côte d'Ivoire (2011), Mali (2013), Central African Republic II (2014), Georgia (2016), Burundi (2017), Bangladesh/Burma (2019), Afghanistan (2020), Palestine (2021), Philippines (2021), Venezuela I (2021) and Ukraine (2022). Two preliminary reviews are currently in progress: Venezuela II (2020) and Nigeria (2020). Eight others have been closed without a decision to prosecute.

The ICC's first trial that of Thomas Lubanga, began on 26 January 2009. On 14 March 2012, he was found guilty of war crimes: enlisting, conscripting and using child soldiers under the age of 15 in Congo. He was the first individual to be convicted by the court. Since then, other individuals have been convicted, including Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi - Sudan - while some have been acquitted, such as Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo - Congo -.

The Court is going through three crises: the announcement of a States cascade withdrawing from its system, another concerning certain practices of the first Prosecutor, Luis Moreno Ocampo, and a third concerning the refusal to authorise an investigation into Afghanistan. The ICC is also the subject of recurrent criticism, most of which is consubstantial with the existence of international criminal justice.

Other points of conflict are the consensus on the legal definition of the concepts of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

The International Criminal Court is not part of the UN and, although it is based in The Hague (Netherlands) like the UN International Court of Justice, it is completely independent from it.

So what is the difference between the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court?

The ICC tries people accused of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, (known as crimina iuris gentium) and recently crimes of aggression, and operates independently of the UN.

The International Court of Justice is the principal judicial organ of the UN and is responsible for settling disputes between states.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is a civil court that deals with disputes between countries. The ICC is a criminal court that prosecutes individuals.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment