What is the UN for?

Etica 13.12.2023 Iñaki Domínguez Translated by: Jpic-jp.org"Peace, dignity and equality on a healthy planet" is the motto of the United Nations. Does the role of the UN still apply today? It has certainly not lived up to the utopian ideal that gave birth to its existence. The latest scandal is of recent weeks: the UN Pension Fund, whose assets amount to a staggering 88.3 billion dollars, has been accused of sacking four of its employees for questioning the wisdom of its investment policies. The sackings have been criticised by two staff unions representing more than 60,000 UN staff worldwide. But like democracy, for now there is nothing better to replace the UN.

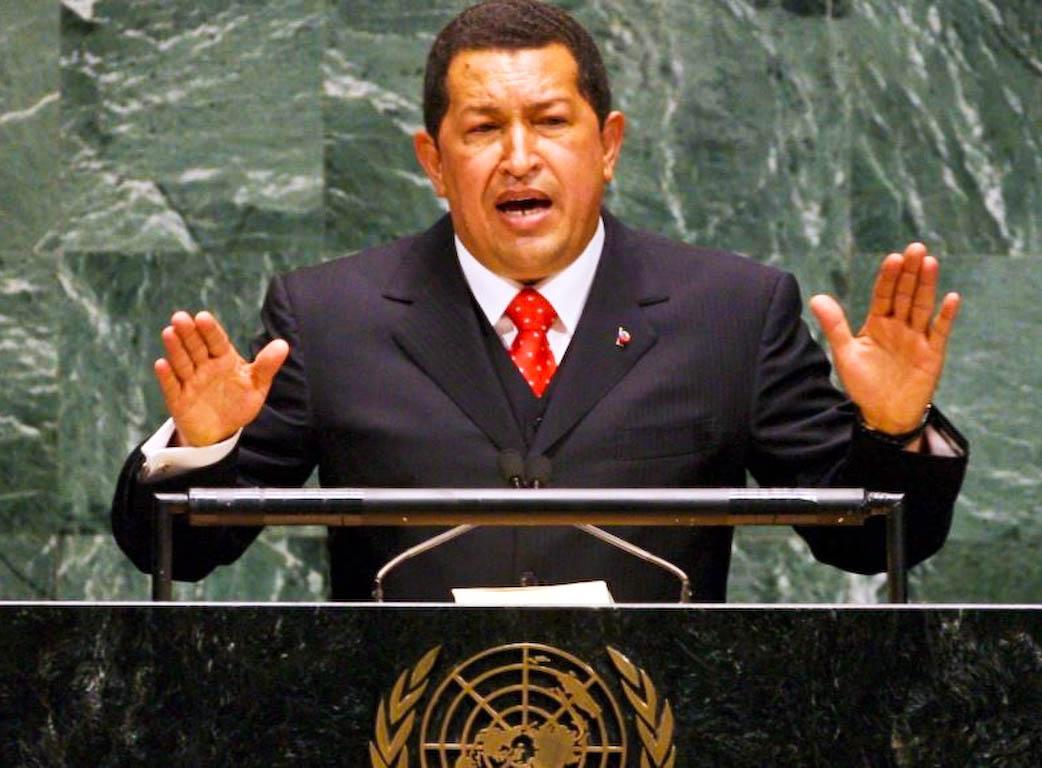

The United Nations is an international, intergovernmental organisation whose primary function is to maintain peace in the world and promote understanding between nations and cultures. It is the world's largest international organisation, with its famous headquarters in New York City.

Last year it had a budget of 3.1 billion dollars, which it draws from the voluntary contributions of its member countries. The UN is supposed to harmonise relations between different countries in order to avoid, above all, the outbreak of armed conflicts. In fact, its origins date back to the Second World War. The idea was to prevent the recurrence of wars as destructive and barbaric as the First and Second World Wars.

It is well known that the first of these wars put an end to the notion of progress and optimism that had dominated Western consciousness since the end of the 19th century. The First World War served to open the eyes of many, particularly the intellectual elites, to the true nature of the human being, his irredeemably violent and selfish self, which seemed to promise a future full of discord, death and destruction. With the atomic end of World War II, the very aggressive nature of the human animal already seemed to point to a nuclear apocalypse, ever present on the horizon during the Cold War and more than conspicuously visible in American films until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

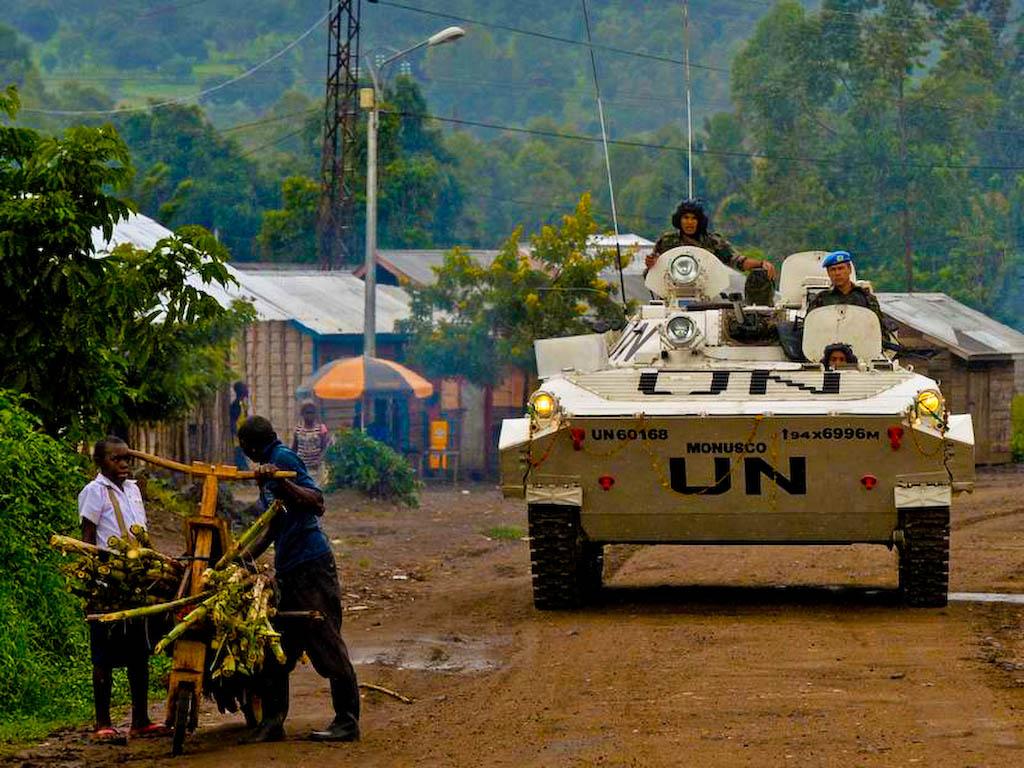

The UN is undoubtedly a much-needed organisation that has served to establish dialogues between antagonistic positions and worldviews, but it has certainly not been able to prevent the emergence and development of major wars over the decades.

One of the most obvious and striking weaknesses of the UN is that it lacks the strength to restrain the warlike impulses of certain nations. For example, the Iraq war, which was launched by the Bush administration using the entire US military and institutional apparatus, was declared illegal by Kofi Annan, then UN Secretary General. The UN itself voted against the war, but its position was not enough to stop the world's leading power.

This brings us back to the philosophy of Hobbes, for whom "man is a wolf to man" (homo homini lupus), and needs a Leviathan (a fabulous sea monster of the Bible) to impose limits on human destructive inclinations. The Leviathan in Hobbes would come to be represented by the state, a unitary entity that imposes a series of conducts on the citizenry and serves to maintain peace and promote social harmony.

In the international case, the UN did not act as such a Leviathan in 2003, but rather the United States, a superpower that did as it pleased by virtue of its superior war power. In this particular case, as in many others in which the UN has been involved, the law of the strongest has prevailed. And whenever the law of the strongest prevails, the UN finds it very difficult to carry out its functions efficiently.

Other criticisms of the UN include its predilection for moral relativism, which is not surprising given the intrinsic function of the UN itself, which is intended to act as an arbiter between divergent points of view. On the other hand, such relativism is typically modern and liberal, not alien to Western culture. As with parliamentarianism, it can be reduced, in philosophical terms, to Kant's epistemological theory, which states that we cannot access the "thing in itself" or understand reality in absolute terms. Thus, reality is understood only in an approximate, partly relative and subjective way, which never allows for full or absolute agreements.

In many other cases, the UN has been criticised for its alleged corruption, lack of democratic spirit, problems in exercising vetoes, and so on. In conclusion, it should be noted that the UN has been a much-criticised organisation but that, in spite of this, it is more than preferable that it should remain in place rather than be dismantled by the cynical spirit of the times. Perhaps it has not lived up to the utopian ideal that gave birth to its existence. [Thus, in a letter to Secretary General António Guterres, the president of the Coordinating Committee of International Civil Servants' Unions and Associations (CCISUA), Nathalie Meynet, says that it is alarming to learn that civil servants are being dismissed for having raised the alarm to their representatives. The classic hypocrisy of preaching good but acting badly]. But that does not make it a dispensable entity in the international framework - far from it.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment