Six Key Points about the UN before its 75th Anniversary (Part Two)

The Conversation 25.06.2020 Pedro Rodríguez Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThe second secretary general of the United Nations (UN), the Swedish, Dag Hammarskjöld, is credited with one of the best definitions to the organization that began 75 years ago in San Francisco: “It has been said that the United Nations was not created in order to bring the society to heaven, but in order to save it from hell.” (See Part One here 1-. Underestimated importance and 2-. Three Founding Principles)

3. Need to reform

Faced with the mandatory challenge of updating itself to the 21st century, the UN has been facing a debilitating tension between rich and poor countries. Members with more resources consider that the organization maintains a bureaucracy that is both excessive and inefficient (including its official head quarter located in New York). In contrast, developing countries view the UN as an exclusive and undemocratic club.

The great dilemma of the UN in its 75th anniversary is that it faces an escalation of ever greater demands and is burdened by a structure that no longer reflects the reality of power in the international system.

To solve this problem there have been persistent calls for its reform. Some have been carried out in a limited way, but the most decisive ones do not succeed. In any case, reforming the San Francisco Charter is not an easy task since it requires ratification by two-thirds of its 193 members, including the five permanent members of the Security Council.

According to the detailed analysis of the budgetary evolution of the UN, published on the occasion of its 70th anniversary by The Guardian, the annual expenditure of the United Nations is forty times higher than what it was in the early 1950s. In this rather expansive evolution, the UN ended up generating a whole bureaucratic universe made up of 17 specialized agencies, 14 funds and a secretariat with 17 departments and more than 40,000 employees on the payroll.

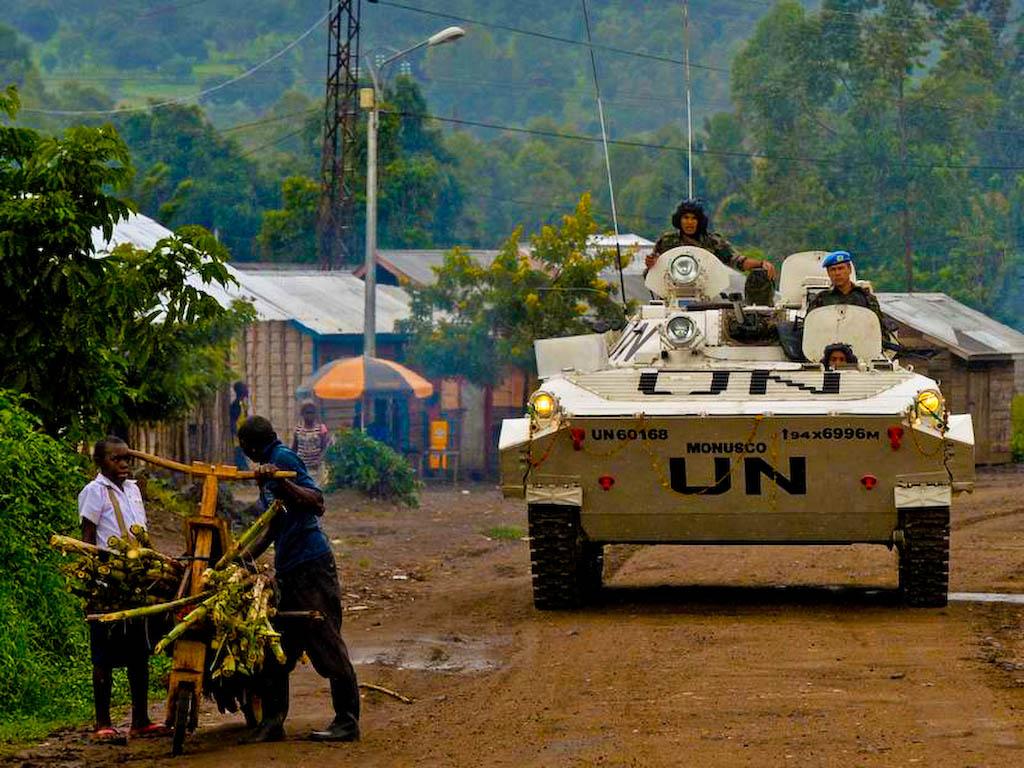

The regular budget – agreed every two years and used to pay basic operating costs – amounts to $2,870 million dollars to the year of 2020. In this sense, the organization has a liquidity problem caused by members who owe more than $1 million dollars in their contributions. Still, the regular budget, with the share of staff costs, represents only a small portion of total spending. Peacekeeping operations take another $6.5 billion annually, with around 110,000 peacekeepers deployed in thirteen peacekeeping operations around the world.

The United States is the country that contributes the most money to the UN, approximately 22% of its regular budget and 28% of the additional budget for peacekeeping operations. At the same time, the United States is also the organization’s largest debtor. The list of countries in debt also includes Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Iran, Israel and Venezuela.

The voluntary contributions of individual governments and philanthropic magnates destined for humanitarian aid, development and specialized agencies such as UNICEF or the World Health Organization must also be added to these payments. This financing channel has multiplied by six during the last 30 years, almost reaching 30 billion dollars.

And yet some agencies insist they are on the brink of bankruptcy. In comparative terms, the United Nations’ total spending would be roughly half New York City’s municipal budget: $75 billion.

4. Democratic deficit

Forged in the final stretch of World War II, the institutional design of the UN had the ambitious objective of creating an effective international governmental organization dedicated to guaranteeing peace and security throughout the planet. Under the philosophy of collective security and also a combination of the two main theories that make up the field of International Relations: Liberalism and Realism.

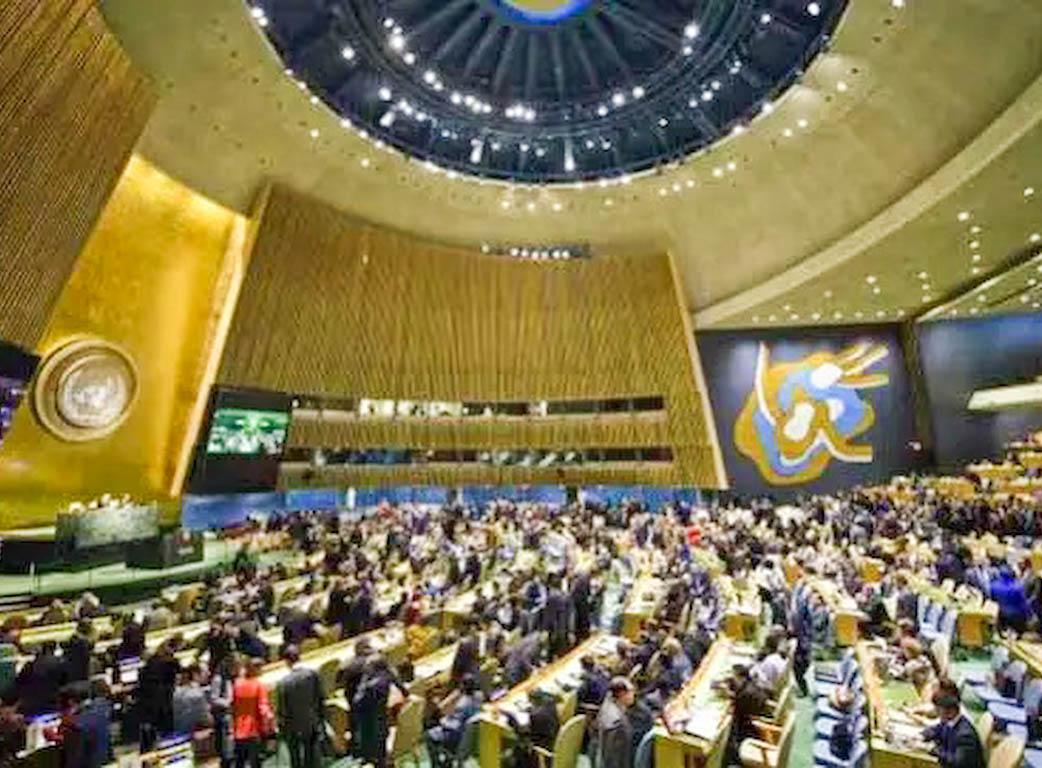

From the point of view of Liberal-Idealism the United States – and the representatives of fifty nations gathered in San Francisco during the spring of 1945 – conceived the General Assembly with equal representation for all its members.

At the same time, they established the Security Council, with binding responsibilities, decisions and five permanent members. In a decisive concession to political realism, the aim was to overcome the inefficiency and lack of representation that during the interwar period weighed down on its antecedent, the League of Nations.

The Security Council – completed with ten more non-permanent members elected for two-year terms – is still a picture of the outcome of World War II. With the right to veto reserved to the winning powers: the United States, Russia, Great Britain, France and eventually the People’s Republic of China after the cornering of Taiwan. The Cold War would turnaround the Security Council into a permanent and sterile pulse for the antagonism between Washington and Moscow.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Security Council has increasingly intervened in situations considered as a threat to international peace and security, as it is said in Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter. This provision allows the Security Council to adopt coercive measures (from economic sanctions to the use of military force) to prevent or deter threats to international peace or respond to acts of aggression.

With the new international order emerging after the Cold War, pressure for a Security Council reform has become the big issue in all debates about the future of the UN. The most repeated argument is that if the Security Council does not include new permanent members – such as Germany, Japan, India, Brazil or South Africa – it risks becoming an anachronistic and irrelevant body, with its primacy questioned in matters of a security peace and taken over by other institutions and entities.

The accumulated failures in conflicts such as Syria and Ukraine, or the coronavirus pandemic itself, together with the abuse of vetoing power, are multiplying the frustration that underlies all these unsatisfied calls to reform the United Nations.

A 3rdand final part will follow. See the original article: Seis claves sobre la ONU ante su 75 aniversario

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment