Where are our international organisations heading?

IPS 18.04.2023 Thalif Deen Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThe massive leak of a treasure trove of highly-classified US intelligence reports - described as “one of the most remarkable disclosures of American secrets in the last decade”, has also revealed a more surprising angle to the story. The US not only gathered intelligence from two of its adversaries, Russia and China, but also from close allies, including Ukraine, South Korea, Egypt, Turkey and Israel.

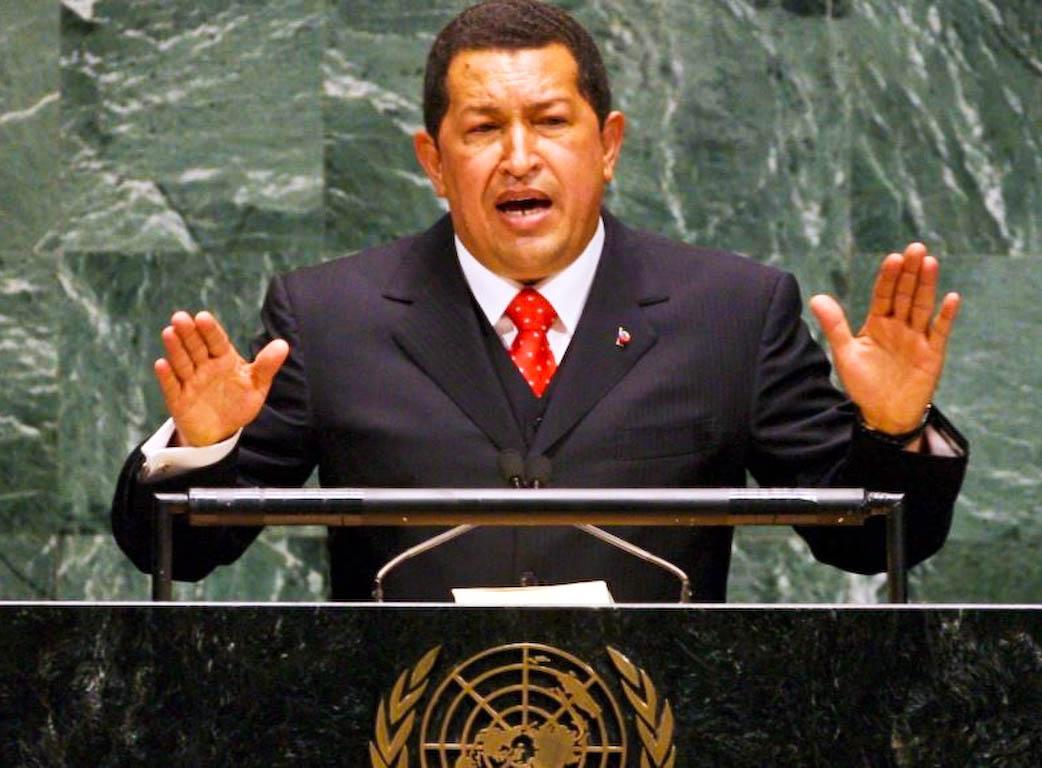

The United Nations, which has long been under surveillance by multiple Western intelligence agencies, was also one of the victims of last week’s espionage scandal. According to the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), one of the US intelligence reports recounts a conversation between Secretary-General Antonio Guterres and his deputy, Amina Mohammed.

Guterres expresses “dismay” at a call from the European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen for Europe to produce more weapons and ammunition for the war in Ukraine. The two UN officials also discussed a recent summit meeting of African leaders, with Amina Mohammed describing Kenya’s president, William Ruto, as “ruthless” and that she “doesn’t trust him.”

Responding to questions at the daily news briefings, UN spokesperson Stephane Dujarric told reporters: “The Secretary-General has been at this job, and in the public eye, for a long time, and “he is not surprised by the fact that people are spying on him and listening in on his private conversations”. What is surprising, he said, “is the malfeasance or incompetence that allows for such private conversations to be distorted and become public.”

At a more global scale, virtually all the big powers play the UN spying game, including the US, the Russians (and the Soviets during the Cold War era), the French, the Brits, and the Chinese. During the height of the Cold War in the 1960s and 1970s, the UN was a veritable battle ground for the United States and the now-defunct Soviet Union to spy on each other.

The American and Soviet spooks were known to be crawling all over the building - in committee rooms, in the press gallery, in the delegate’s lounge, and, most importantly, in the UN library, which was a drop-off point for sensitive political documents.

The extent of Cold War espionage in the UN was laid bare by a 1975 US Congressional Committee, named after Senator Frank Church (Democrat-Idaho) who chaired it while investigating abuses by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), National Security Agency (NSA), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The evidence given before the Church Committee in 1975 included a revelation that the CIA had planted one of its Russian lip-reading experts in a press booth overlooking the Security Council chamber so that he could monitor the lip movements of Russian delegates, as they consulted each other in low whispers.

Dr Thomas G. Weiss, who has written on the politics of the UN, told IPS: “As you say, it is hardly surprising that US intelligence services spy on the 38th floor. This is an ancient practice”. He pointed out there is almost nothing that they don’t monitor. Indeed, it should come as a source of relief to UN fans that Turtle Bay is still taken seriously enough to spy on. “The justification for the monitoring would be more intriguing”, he said. “Is the Secretary General pro-West (he has criticized the Russian War), or pro-Russia (according to rumours)?,” said Dr Weiss.

In his 1978 book, “A Dangerous Place,” Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a former US envoy to the United Nations, described the cat-and-mouse espionage game that went on inside the bowels of the world body, and particularly the UN library.

Back in October 2013, Clare Short, Britain’s former minister for international development, revealed that British intelligence agents had spied on former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan by bugging his office just before the disastrous US invasion of Iraq in March 2003. The UN chief was furious that his discussions with world leaders had been compromised. As she talked to Annan on the 38th floor of the UN building, Short told the BBC, she was thinking, “Oh dear, there will be a transcript of this, and people will see what he and I are saying.”

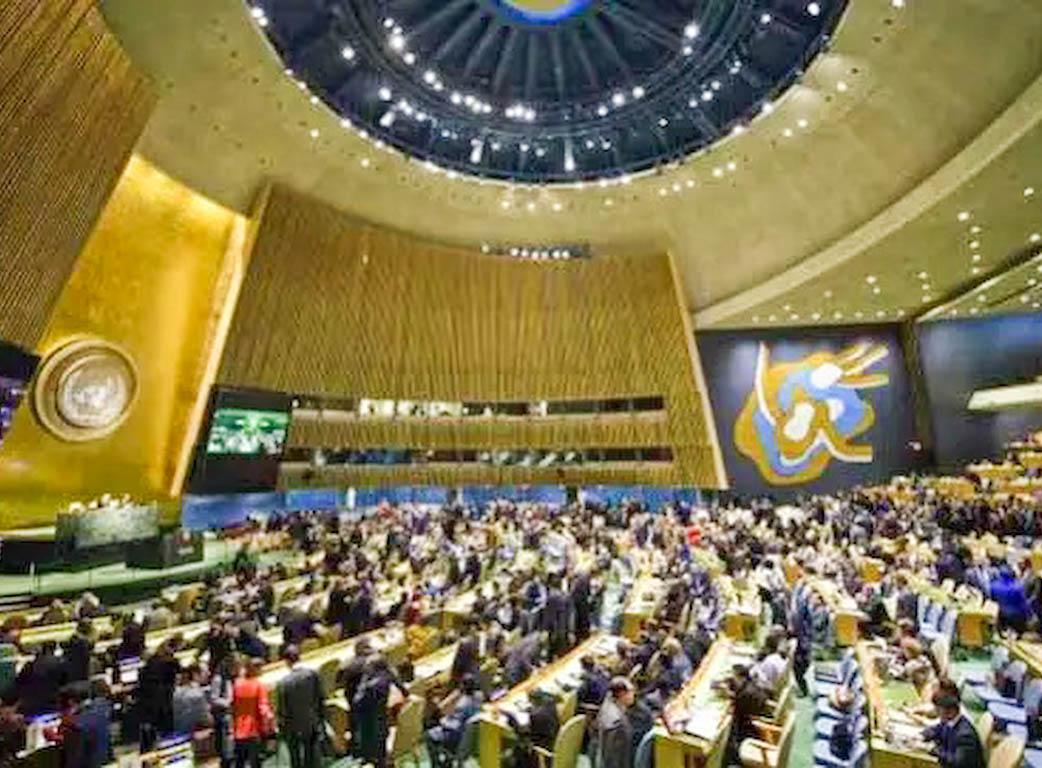

The United Nations, along with the 193 diplomatic missions located in New York, has long been a veritable battleground for spying, wire-tapping and electronic surveillance. Back in September 2013, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff, throwing diplomatic protocol to the winds, launched a blistering attack on the US for illegally infiltrating its communications network, surreptitiously intercepting phone calls. Justifying her public criticism, she told delegates that the problem of electronic surveillance goes beyond a bilateral relationship. “It affects the international community itself.” Rousseff unleashed her attack even as US President Barack Obama was awaiting his turn to address the General Assembly on the opening day of the annual high-level debate. By longstanding tradition, Brazil is the first speaker, followed by the US. “We have let the US government know our disapproval, and demanded explanations, apologies and guarantees that such procedures will never be repeated,” she said.

According to documents released by US whistle-blower Edward Snowden, the illegal electronic surveillance of Brazil was conducted by the US National Security Agency (NSA).

The Germany Der Spiegel magazine reported that NSA technicians had managed to decrypt the UN’s internal video teleconferencing (VTC) system, as part of its surveillance of the world body. The combination of this new access to the UN and the cracked encryption code led to a dramatic improvement in VTC data quality and the ability to decrypt the VTC traffic. In the article, titled “How America Spies on Europe and the UN”, Spiegel said that in just under three weeks, the number of decrypted communications increased from 12 to 458.

Subsequently, there were new charges of spying - but this time around the Americans were accused of using the UN Special Commission (UNSCOM) in Baghdad to intercept Iraqi security intelligence in an attempt to undermine, and perhaps overthrow, the government of President Saddam Hussein. The charges, spread across the front pages of the Washington Post and the Boston Globe, only confirmed the longstanding Iraqi accusation that UNSCOM was “a den of spies,” mostly American and British.

Established by the Security Council immediately after the 1991 Gulf War, UNSCOM was mandated to eliminate Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction and destroy the country’s capabilities to produce nuclear, biological and chemical weapons. The head of UNSCOM, Richard Butler, however, vehemently denied charges that his inspection team in Iraq had spied for the US. “We have never conducted spying for anyone,” Butler told reporters.

Asked to respond to news reports that UNSCOM may have helped Washington collect sensitive Iraqi information to destabilize the Saddam Hussein regime, Butler retorted: “Don’t believe everything you read in print.” Around the same time, the New York Times weighed in with a front-page story quoting US officials as saying that “American spies had worked undercover on teams of UN arms inspectors ferreting out secret Iraqi weapons programmes.”

In an editorial, the Times said that “using UN activities in Iraq as a cover for American spy operations would be a sure way to undermine the international organization, embarrass the US and strengthen Mr. Hussein.” “Washington did cross a line it should not have if it placed American agents on the UN team with the intention of gathering information that could be used for military strikes against targets in Baghdad,” the editorial said.

Samir Sanbar, who headed the Department of Public Information (DPI), said monitoring international officials evolved with enhanced digital capacity. What was mainly done by security agents widened into a public exercise, he added. Initially, he said, certain UN locations of interest like the Delegates Lounge were targeted by several countries, including with devices across the East River in Queens or across the lounge adjacent to the UN Lawn –and within shouting distance of permanent missions and residences of UN diplomats.

One senior UN official once said the closer he drove towards the SG’s residence at Sutton place the more obvious was the radio monitoring. “I recall a meeting with Kofi Annan the day US President Bush announced the invasion of Iraq. He had suggested a “tete a tete” - the two of us alone. While expressing his concern, and seated outside on lounge chairs, “we noted helicopters circling around The Secretariat building.”

“When I mentioned “Black Hawk Down” –relating to Somalia’s experience– he nodded and smiled casually. Kofi was a dignified colleague and an outstanding Secretary General who rose from the ranks, and inspired the whole Secretariat staff.”

Meanwhile, when the UN Correspondents Association (UNCA) held its annual award ceremony in December 2013, one of the video highlights was a hilarious skit on the clumsy attempts at spying going on inside the highest levels of the Secretariat - and right up to the 38th floor offices of then Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. When I took the floor, as one of the UNCA award winners, I gave the Secretary-General, standing next to me, an unsolicited piece of light-hearted advice: if you want to find out whether your phone line is being tapped, I said jokingly, you only have to sneeze loudly. A voice at the other end would instinctively– and courteously– respond: “Bless you”. And you know your phone is being tapped, I said, amid laughter.

See, When US Spies Read Russian Lips in the Security Council Chamber

Photo. The UN Security Council chamber has been the scene of espionage by both sides. © UN

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment