China, between war and peace

Ethic 12.07.2024 Jara Atienza Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgIn recent years, the Asian giant has tried to set itself up as a great international peacemaker, while at the same time stepping up its belligerence against territories it considers its own. How has it managed to maintain this ‘balance’, and what does the future hold?

Since the triumph of the Communist revolution, one of China's great ambitions has been to become a major world power. And to claim the territories it considers to be its own. It has even set a date to achieve this: 2049, the centenary of the founding of the People's Republic of China.

This is why, for some years now, it has structured its foreign policy around the principles of peaceful coexistence. In practice, however, this concept has become more elastic as the country has gained weight on the geopolitical stage. This is how it came to claim the role of great peacemaker in the new world order.

In March 2023, a year after Russia invaded Ukraine, Beijing launched a peace plan welcomed by both sides. A month later, it surprised the world by announcing that it had succeeded in getting Saudi Arabia and Iran to re-establish diplomatic relations after seven years of confrontation. It then offered to mediate between Israel and Palestine, at a time when Hamas had not yet attacked the Jewish state and Israeli forces had not yet stormed Gaza. It then turned its attention to East Africa, being one of the first countries to call for a ceasefire in Sudan.

China's efforts to act as a mediator in international conflicts are, however, far from new. For Inés Arco, a researcher at the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB in Spanish acronym) and a specialist in East Asia, they began in 2008. ‘While the United States and Europe were facing the financial crisis, China, which was hosting the Olympic Games that year, weathered the situation very well and gained confidence in international forums; it began to see that it could play a more important role on the world stage’, she explains.

The ‘war wolves’

This confidence was confirmed in 2013, when Xi Jinping took over the reins of a country that had already become the world's second-largest economy. That year, he launched the ‘New Silk Road’, also known as the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative. This infrastructure and investment megaproject to link several continents has been accompanied by an unprecedented surge in international arbitration proposals.

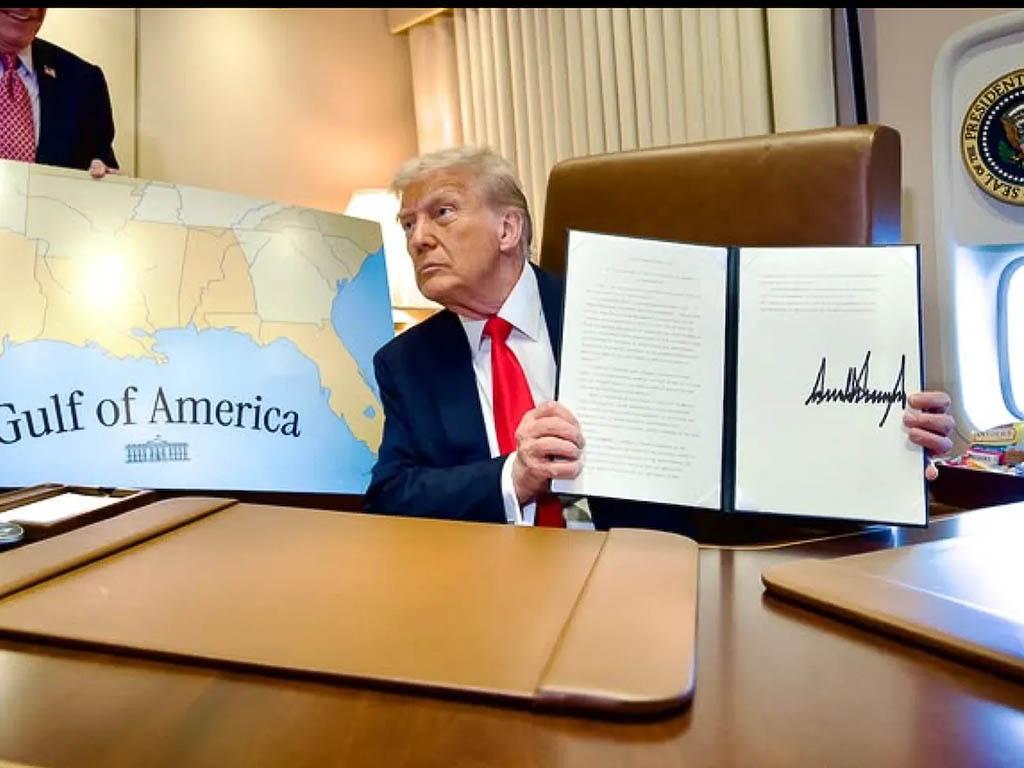

In 2017, the country arbitrated nine disputes, compared with just three at the start of Xi's term. Since then, Chinese diplomacy has taken several turns. ‘Former President Donald Trump's constant criticism, the Trump-initiated trade war and the pandemic marked a turning point and China adopted a more assertive diplomatic approach,’ explains Arco.

Chinese officials around the world quickly began making statements and posting sarcastic and aggressive messages. They seemed prepared to do anything to defend their national interests, including stirring up tensions with any country, enemy or ally. Some diplomats even crossed red lines, such as the Chinese ambassador to France, Lu Shaye, who, via the embassy's Twitter feed, called a French analyst a ‘little thug’, a ‘rabid hyena’ and an ‘ideological troll’. The tone was such that this attitude was described as ‘wolf diplomacy’.

What has changed for China to return to moderation? The harsh ‘zero covid’ policy, which kept the country closed, damaged China's booming economy. When the ‘prison’ opened at the end of 2022, Xi's first objective was to resuscitate its markets. To achieve this, he sought to regain a prominent place on the international stage: he once again took part in major summits and presented his country as a key player in global stability.

‘Before intervening in a conflict, however, Beijing calculates a number of variables’, explains the CIDOB researcher. ‘Beijing examines whether there are important economic interests or security concerns in one of the countries, whether mediation reinforces its image as a peaceful and responsible power, and whether it can act as a counterweight to the United States.

Xi remains determined to confront what he calls American hegemony’’. That is why, in speech after speech, the Chinese leader highlights his rival's failures in Iraq and Afghanistan. Manuel Valencia, former Spanish ambassador to China, explains that over the last 40 years, only the United States has dealt the cards in the game of international politics. But China has launched an alternative in which, a priori, it is not human rights or ideologies that count, but the establishment of mutually beneficial trade agreements.

‘China has always repeated that its model cannot be exported to the rest of the world: it is very firmly rooted in its own Confucian civilisation, which makes it difficult to imitate. But it has money, economic interests, technology and political stability without electoral turmoil. Nor does it preach to the world, which is very irritating to Indians, Chinese, Arabs and Africans, who are not descendants from the Enlightenment philosophy or the Montesquieu’s separation of powers. Chinese diplomacy is ‘flexible’ in its relations with governments whose rapprochement is only just beginning, it does not judge’, explains Mr Valencia.

A prey dog at home

Arco agrees: ‘China maintains that the absence of peace is due to a lack of development, not a lack of democracy. That's why its peace proposals are not aimed at the West and its allies, but ‘at the countries of the South’, which it sees as potential partners’. This is why it insists on presenting itself as a country with no deaths to its credit, which has not invaded any territory and has not engaged in proxy wars, even though it has annexed Tibet and has disputes with several of its neighbours.

This double facet becomes clearer the closer you look at the map. While it tries to seduce part of the world with a pacifist and well-meaning image, China appears like a prey dog on the verge of attacking its neighbours. Just look at how it has stepped up the pressure on Taiwan, an autonomous territory it considers a ‘rogue province’ and wants to regain control of. It has declared itself ready to use force against anyone who gets in its way. Hence the constant dispatch of fighter planes, warships and even spy balloons to the Straits and the intensification of military manoeuvres: a warning to the United States, which has pledged to defend the island.

Xi has increased his military spending, modernised his arsenal and prepared his army. This show of military strength comes on top of the expansion of its nuclear arsenal, according to a report by the Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

It may seem contradictory for China to advocate peace in the world while preparing for an imminent conflict. It is far from it. On the one hand, it knows that to be the economic benchmark it wishes to be, it must engage with the world in a friendly manner. But on the other hand, it is aware that to establish itself as the great superpower of the 21st century, it must be able to defend what it considers to be its own. For the time being, the double game of war and peace seems to be played out on an increasingly fluid chessboard.

See, China, entre la guerra y la paz

Illustration © Óscar Gutiérrez

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment