The nationalist impulse

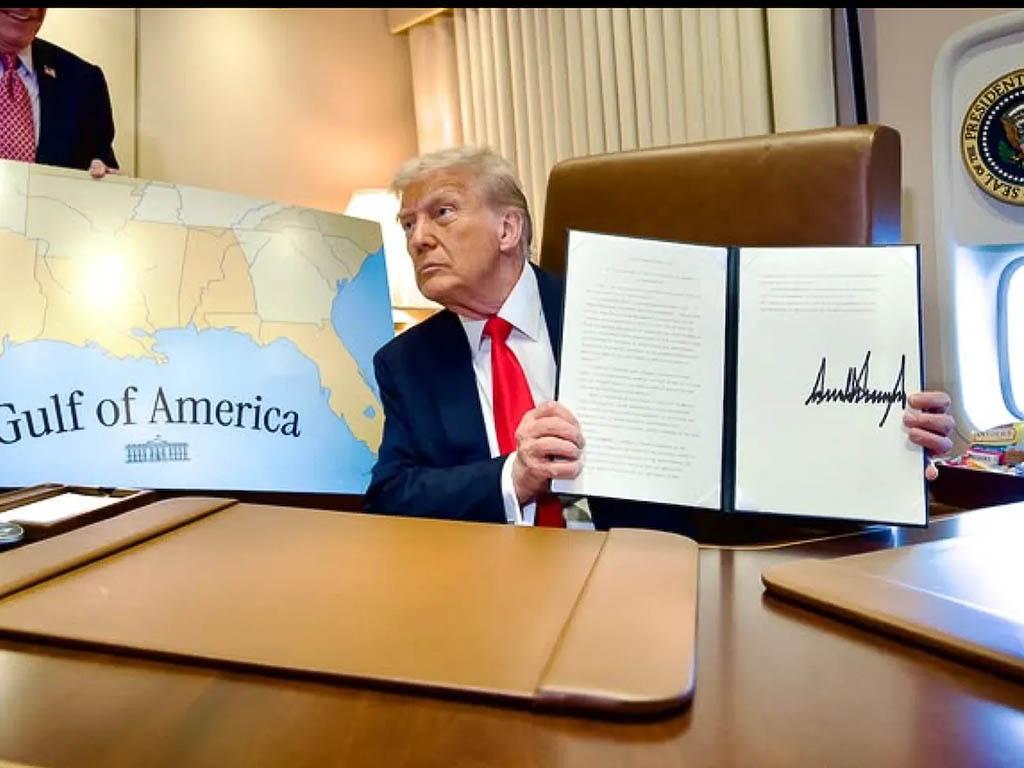

Ethic 03.06.2024 Manuel Arias Maldonado Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgFrom Trump's ‘Make America Great Again’ to the ‘Take Back Control’ of the British Eurosceptics, via the aggressive Russian irredentism, Catalan independence or the growing rejection of immigration in a large part of the developed world, these are bad times for cosmopolitan lyricism.

That nationalist passions continue to be so strong well into the 21st century, more than a hundred years after the inter-war period that saw the establishment of fascist regimes on European soil and the aggressive performance of a nationalist-based Japanese imperialism, is nothing short of perplexing. Had humanity not sworn to keep its ethnicist inclinations at bay? There is perhaps no better example of this apparent historical incongruity than the Catalan case: Spain's richest region staged a revolt against the constitutional order of a democratic state whose power has been decentralised for more than forty years. But there is more: from Trump's Make America Great Again to the Take Back Control of the British Eurosceptics, via aggressive Russian irredentism, the rise of Hindu nationalism or the growing rejection of immigration in much of the developed world, these are bad times for the cosmopolitan lyric.

However, it is important to distinguish between the different manifestations of the phenomenon. On the one hand, there are the sub-state nationalisms that demand autonomy or the right to secede. They are somewhat anachronistic: the formation of European nations took place in the period from the French Revolution to the end of the Great War, and Catalan separatists have tried to reproduce this logic in the framework of a European Union founded against nationalism; the same is true for Scotland and Quebec.

On the other hand, we find the strengthening of nationalist praxis in consolidated states: authoritarian governments with an imperial past (Russia, China), democratic governments led by nationalist-oriented parties (India, Italy, Great Britain, Israel), or political parties and leaders - generally right-wing - that act within existing democracies (from Trump to Wilders, via Alternative for Germany or Vox). In these cases, the nation that serves as the basis of the state is exalted; sometimes the minorities that are part of it suffer as a result.

But why should this be surprising? If one looks at it closely, nationalism is characterised by its historical continuity; instead of following a declining trajectory in accordance with the learning capacity of human societies, nationalism maintains a constant presence in them that exhibits different forms depending on the circumstances. The casuistry is varied: while the democratic Germany that emerged after the defeat of Nazism refrains from expressing national passions and even maintains a modest relationship with its flag, without this in turn having generated separatist vocations in any of its Länder, the weakening of national sentiment in post-Franco Spain has been accompanied by the strengthening of internal nationalisms.

Nor should it be forgotten, finally, that national affections have their ambiguity: when young Americans went to die in Europe and the Pacific, patriotism played a decisive role in motivating sacrifice; at the same time, however, the US government interned its citizens of Japanese origin in internment camps. And, as the American philosopher Richard Rorty said, taking a progressive view, perhaps a country cannot prosper if its citizens do not love it.

Precisely, as John Kane has pointed out, nationalism is an uncomfortable object of analysis because it is about passions rather than reasons; we don't quite know what to make of that. Indeed, any discussion with a nationalist is doomed to end in the dead end of sentimental attachment. The problem is that, as history has taught us, love of nation can take an aggressive and even violent form. Just as there is almost everywhere that ‘banal nationalism’ of which Michael Billig speaks, expressed in symbols and practices that seem natural to us because we have been socialised with them, there is a nationalism bent on indoctrinating policies that often transmit to their recipients an unhealthy combination of victimhood and supremacism.

It thus seems reasonable to distinguish between two ideal types of nation - civic nation and ethnic nation - in order to orient ourselves in the confusing landscape of modern societies. The civic or political nation is based on constitutional rights and freedoms granted by the state; its sentimental basis is, in principle, secondary. By contrast, the ethnic or cultural nation is organised around a cultural identity to which its members are affectively attached. Broadly speaking, this is a plausible distinction. But it is not an exclusive opposition, but rather a continuum that allows for gradations and overlaps. No state has yet legitimised itself by appealing solely to the cold-civic rationality of the inhabitants of a territory; the national foundation of the state refers to a collective imaginary - often the subject of dispute - which manifests itself in narratives with binding force.

It cannot be deduced from this, however, that we are all equally nationalist or that all nations are equal. For a liberal state that respects pluralism and the freedom of the individual to shape his or her identity will be preferable to one that engages in socialising its citizens into an exclusionary identity or is aggressive towards its neighbours.

The question remains about the validity of the most aggressive nationalism: how is it that it continues to overshadow the fate of human societies? Perhaps this is not so difficult to answer. It is not for nothing that we are socialised in particular environments and - even if being born in one place or another is the greatest of contingencies - we attach a higher emotional value to that which is more familiar or closer to us. Our psychobiological constitution reinforces this disposition: natural evolution has prepared us to seek the cohesion of the group of which we are a part. Herein lies the key to nationalist vigour: the passions of belonging are dormant at all times, waiting for a political agent to try to activate and mobilise them. It may do so in a benign way, for example by calling for the reconstruction of a country after a war; or the opposite. And while there will be cosmopolitan-oriented citizens indifferent to such appeals, the truth is that cosmopolitans are in short supply.

So beware: perhaps it is to be welcomed that ethnicist nationalism does not play an even more decisive role in the life of our societies. It could be worse. And no one can rule out that one day it will not.

Illustration by Óscar Gutiérrez

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment