Expectations in view of the Synod

Vita Pastorale 29.05.2024 Severino Dianich Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgA desired overcoming of an inveterate clerical mentality cannot solve the problem of synodality. A change in canonical legislation is indispensable.

Along the Synodal Way, there have been questions, issues, and needs for the Church’s reform, which have aroused many expectations, now focused on the second session of the Synod and on the decisions that the Pope will make afterwards. The expectations are many, too many for some not to be disappointed. But, if those most pertinent to the Synod's theme, namely the promotion of synodality, are not answered, it would be a step backwards instead of forwards. Much ado about nothing?

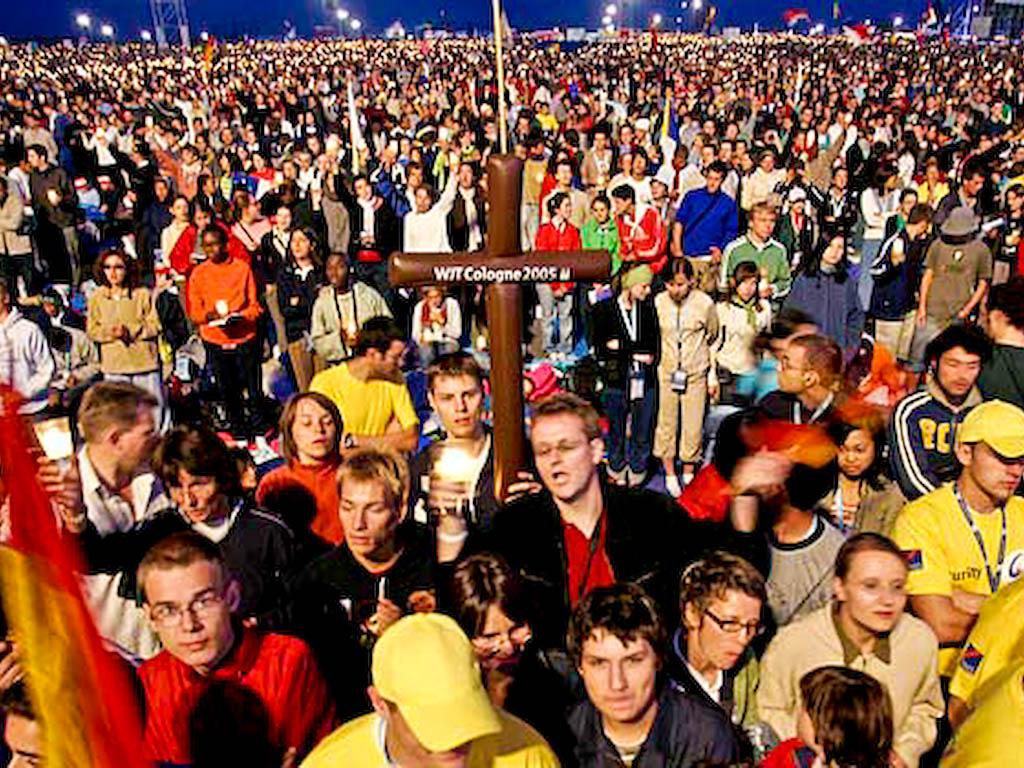

The promotion of synodality aims at the faithful’s maturation of the faith and spirituality. In the development of living, the human person emerges from the condition of minority, when he or she is recognised as having the capacity to decide, on himself or herself and, together with others, on the life of the community.

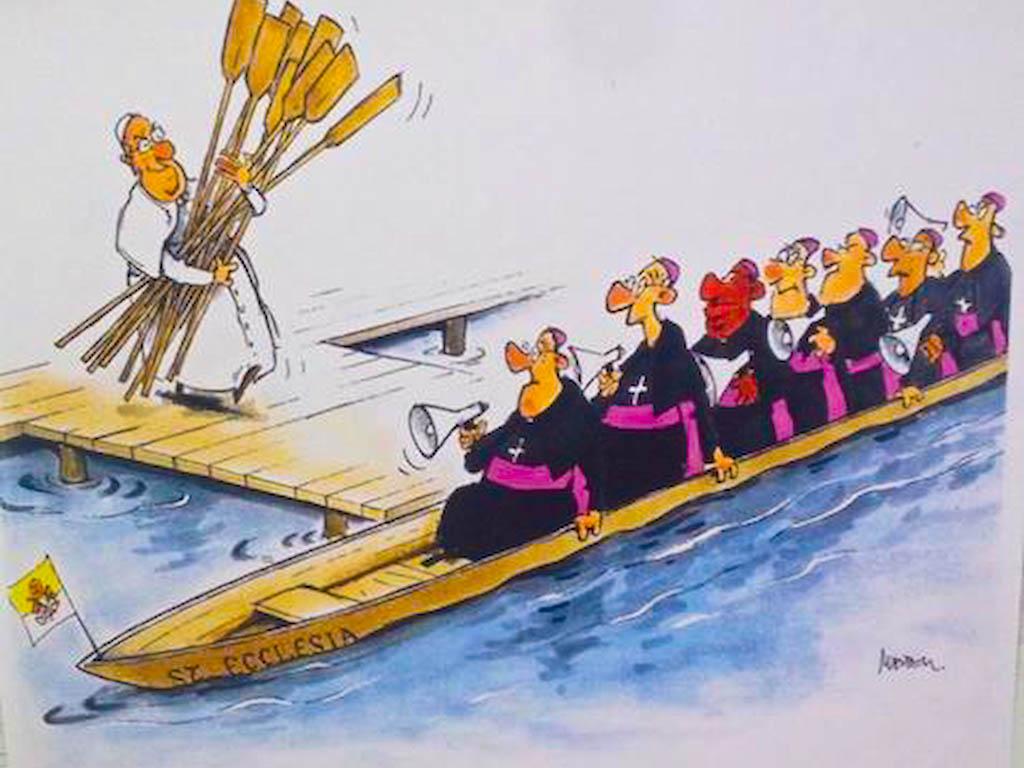

Today, in fact, according to the Code of Canon Law, the faithful, including deacons and priests, do not have, even in areas where the doctrine and discipline of the sacraments are not at stake, any instance in which they are recognised as having the capacity to decide with a vote what concerns the life of the diocese. Nor, lay faithful, in the life of the parish. The councils currently provided for, with few exceptions, only enjoy an advisory vote. A desired overcoming of an inveterate clerical mentality, therefore, cannot solve the problem of synodality. A change in canonical legislation is indispensable.

Browsing through the documentation on the various stages of the Synodal Way and reading the Synthesis Report of the October 2023 assembly, it is striking that, on the participation of the faithful in the decisions, the question of women in the Church is particularly insisted upon. If the issue involves all the faithful, why is it particularly insisted upon with regard to women?

The answer, although it opens uncomfortable questions, is inevitable: because decision-making capacity is reserved for ordained ministers and women cannot receive the sacrament of Holy Orders. This seems to place her, inevitably, in a state of minority.

A frequently proposed way to deal with the problem is to set up new ministries to which women could also have access, entrusting them with the pastoral care of a community. This is a viable path. It is important, however, that it does not result in a restoration of the division between Order and jurisdiction, which the Council intended to overcome. The priest, as is already the case in some situations, cannot be reduced to spending his days in his car, on his motorbike or on a boat to go and celebrate masses here and there, while others would have the ministry of pastoral care of the community.

The fact that half of all humans are precluded from accessing a sacrament, just because they are women, in fact, fair or unfair, constitutes for many a stumbling block in their journey towards faith. It is not only women, nor is it only women who would like to be ordained, who are asking the Synod and the Pope to open up the diaconal ordination of women. It is a reasonable question, a good thing, the fulfilment of which would benefit many Christian communities. To answer with a ‘no’, without giving absolutely cogent reasons to the contrary, cannot but give women the feeling of being discriminated against. Now no one could say that the reasons usually given for answering with a ‘no’ are absolutely cogent. The Synod's synthesis report of the past session notes that, alongside those who consider tradition absolutely contrary, there were also those who judged that ‘granting women access to the diaconate would reinstate a practice of the early Church’.

The question of tradition, therefore, does not offer an unambiguous answer from historians. Not only that, but it is the entire tradition on the sacrament of Holy Orders that has gone through countless changes. Suffice it to recall that the Second Vatican Council eliminated a degree of the Order, the subdiaconate, which Trent had defined as one of the three major orders. The Tridentine Council then did not include in the three degrees of the Order the episcopate, considered a jurisdictional ministry, which instead Vatican II defines as summum sacerdotium, sacri ministerii summa (LG 21). The ministry of preaching, which according to Vatican II ‘the bishops, as successors of the apostles, receive from the Lord’ (LG 24), is not mentioned in the doctrinal decree of Trent. A curious episode during the Council debate was the intervention of one of the Fathers according to whom it was not possible to define the ministry of preaching de iure divino, because it would be tantamount to declaring that bishops and popes all lived in a state of mortal sin. For centuries, in fact, popes did not preach and bishops, only a few, and exceptionally did. These are certainly not minor variations.

In conclusion, tradition shows that the Church, in the exercise of its legitimate Magisterium, can introduce changes in the understanding of doctrine and the practice of ordained ministry. A Council, or the Pope alone, lawfully and validly can ordain women to the degree of the diaconate. If, in response to today's expectations, the Pope does so, it will be a great good for the Church.

Not that such a reform would solve all the problems, but it would be an important sign of a turning point in progress towards the fuller fulfilment of the doctrine of Vatican II. There is therefore no inequality in Christ and in the Church with regard to race or nation, social condition or sex, for “there is neither Jew nor Gentile, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female: all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (LG 32).

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment