It's not ‘a revolution, but a change is underway’.

Télérama 29.10.2024 Elise Racque Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThe role of lay people, the place of women, the evaluation of bishops... After three years of worldwide consultations, on 26 October the Church gave birth to a document outlining its future. Sociologist Danièle Hervieu-Léger looks at the progress made, and its limitations.

For the past three years, the Catholic Church has been engaged in a worldwide consultation process initiated by Pope Francis, known as the ‘Synod on Synodality’. In other words, Catholics from all over the world had the opportunity to give their opinion on the future of their Church, which has been weakened by a drop in vocations and by sexual and spiritual violence committed within it. In particular, they were invited to express their views on the role of bishops and the place of lay people - men and women - in liturgy and decision-making. The summaries, sent to the Vatican from every continent, ranged from bold proposals - such as the ordination of women - to more conservative ones.

This October, the synodal assembly, made up of 368 members, 75% of whom were bishops, was tasked with drawing up a final document setting out the guidelines. For the first time, lay people, including 54 women, were given the right to vote in the drafting of this text, which was published on Saturday 26 October.

What were the results? There has been no revolution on the most sensitive issues, which have been entrusted to autonomous working groups that will deliver their conclusions in the coming June. The two-thousand-year-old institution, aware of the discord that runs through it, is not crossing the red lines that would shatter its unity, but it is initiating a movement towards greater horizontality. Religious sociologist Danièle Hervieu-Léger takes a closer look at this tightrope walk.

In your opinion, is this Synod the start of a far-reaching reform, or is it the birth of a mouse?

Neither! We're not witnessing an institutional revolution, but what happened during this Synod is far from negligible. A change of culture is taking place, first and foremost in the very fact that the Church is consulting its faithful to think about its future. The practical arrangements for the discussions held in Rome over the last few weeks, bear witness to a change in style: clerics, lay people, men and women debated around round tables that physically displayed a form of horizontality.

In the form of more or less insistent advice and recommendations, the final document invites us, as best we can, to implement this participative style in our ecclesial practices. The idea is to ensure a more active and effective presence of lay people in the running of community life, which implies a real shift in the way authority is presented. For example, the text calls for parish and diocesan councils to be made compulsory, where lay people can give their opinions and take part in decision-making. One proposal recommends that more women be involved in the seminaries where priests are trained. Another recommends broadening the tasks that a bishop can delegate. The notion of ‘accountability’ is mentioned several times: it suggests that the authorities should be accountable to the faithful for their actions, and the idea that bishops, right up to the Curia, should be subject to evaluation is emerging. This is certainly an expression of a desire for change, but the limits of the exercise are quickly reached.

No real change in the organisation of power?

The Synod did not go as far as was outlined in an initial working document. Although parish and diocesan councils have been made compulsory, the idea that their members should not all be appointed by the bishop or the parish priest is no longer clear. The creation of a preaching ministry enabling lay men and women to give homilies has also not been taken up. It is therefore an inflection in style, but it does not concretely call into question the exclusive decision-making power of the priest or the bishop. Although co-responsibility between clerics and lay people (including women, of course) is regularly emphasised, it is played out on the terrain of exchange and consultation - which is no mean feat and already goes beyond the limits acceptable to the most conservative - but concrete progress is timid.

The Synod acknowledged the need for reform, but inevitably came up against the stumbling block that is blocking any development of the Roman system: the definition of the priest's sacred authority, which his divine election (the famous ‘call’ to which the priestly vocation is supposed to respond) establishes as the only legitimate mediator of the faithful's relationship with the divine. Wanting to create more horizontality and fluidity in relations between the lay faithful, priests and bishops, but without touching the verticality of power that underpins this definition of the priest... It's like squaring a circle.

Although it had been ruled out by the Pope, the question of women's access to ordination as deacons remains, according to the final text, ‘open’. How is this about-turn to be understood?

To tell the truth, we no longer know whether this question is open or closed. A working group is due to reflect on this crucial issue until June. This creates a troubling delay. Is it a question of continuing to reflect on the extent to which this issue is crucial to the Church's credibility in today's world? Or is it a delaying tactic to postpone the reaffirmation of the pontifical ‘no’, which has already been clearly stated? It's hard to know. During the Synod, the subject was alternately on the agenda and then put aside. It returned to the heart of the discussions during the final days of the assembly, thanks to strong pressure exerted by certain members in favour of opening up the diaconate to women.

The stakes involved in women's access to ordained ministry are enormous. If this path is opened up, it implies a radical questioning of the sacred figure of the priest, identified as another Christ, and who as such can only be thought of as male and celibate. Behind this male privilege there is also something of the archaic vision of the sacred incapacity of women, whose periodic ‘impurity’ distances them from the space of the sacred. If women enter the game, even though through the back door of the diaconate, this construction of the priesthood collapses, and with it the hierarchical edifice that is the backbone of the Roman system.

Nevertheless, one paragraph of the synod's summary states that there should be no obstacles preventing women from taking on the leadership roles that canonical texts allow them. Is this a major step forward?

Yes, and no. In this paragraph, the Church acknowledges that there is a problem, and reaffirms the equal dignity of baptised men and women. Everything that canon law authorises is open to women, but everything that canon law excludes... remains excluded. In reality, in many places where the number of priests is in freefall, women already play very important roles: they celebrate funerals, prepare marriages, take charge of catechesis, run training courses, etc. They are already ‘guides’. The text does not add much new, except to recognise that this role is not sufficiently taken into account or facilitated in many places. But that's as far as it goes. It is likely that the Pope himself is completely ambiguous on this subject. His concern to strengthen the place of women in the institution is certainly sincere, but his regular insistence on the ‘feminine specificity’ of their vocation shows the extent to which he remains trapped in a patriarchal culture, and under the pressure of conservative currents that oppose any change tooth and nail.

By consulting Catholics from all over the world, the Synod has highlighted the profound disparities in the expectations and red lines of the faithful on different continents. To reform itself, does the Roman institution need to decentralise?

Since the Council of Trent, the unity of the Church has been conceived in terms of uniformity. Today, however, it is confronted by its extreme internal pluralisation, which is not new, but which is now being publicly asserted; differences - for example, on the place of women or the acceptance of homosexual believers - threaten to constitute dividing lines. The Synod is attempting to deal with this by inviting greater consideration to be given to the cultural context of local communities... but without touching canon law, which formalises the uniformity of institutional operation. Theologians have suggested that the autonomy of national or continental bishops' conferences to take decisions concerning their territory should be recognised, but this much-debated passage does not appear in the final document. How can homogenising unity be reconciled with the autonomy of local communities? The equation seems insoluble.

Are some of the differences schismatic in nature?

In the document resulting from the synod, one point is certainly intolerable for those who howl at the Protestantisation of Catholicism: the text suggests inviting representatives of other Christian denominations to take part in parish and diocesan councils. Unthinkable for some! In the future, a schism could occur in one of two ways: an active break by some who would declare that Rome is no longer in Rome; or a dissolution of unity, a gradual estrangement between the different components of Catholicism. This silent schism is, in many respects, already underway.

To what extent will the Synod's recommendations be implemented?

The question is how they will be received. By announcing that he would not be publishing a post-synodal apostolic exhortation, contrary to usual practice, the Pope is giving official (magisterial) value to the final text published on 26 October, which he is presenting as a guide available to all. He chose not to put his authority forward, in line with the desire for horizontality that emerged from the synod. What happens next is essentially in the hands of the bishops, and their reactions will reveal the balance of power present.

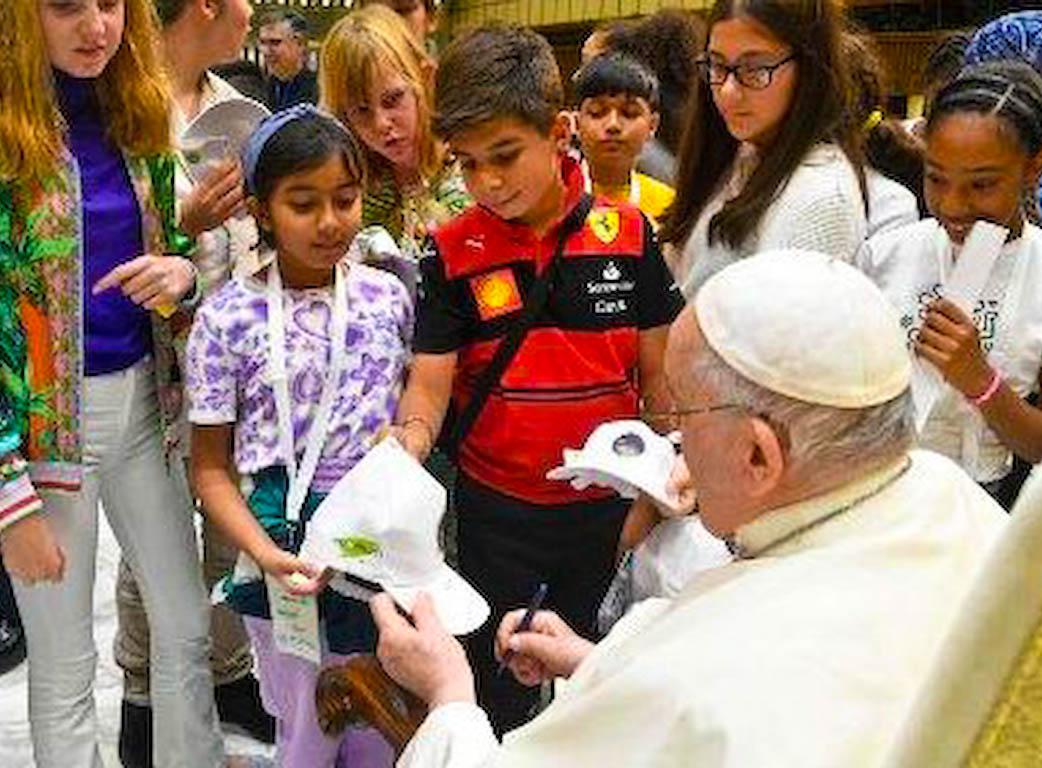

Photo. Pope Francis at the Vatican, during the XVI Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops, 26 October 2024. Photo Remo Casilli/REUTERS

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment