A church to be reformed and purified

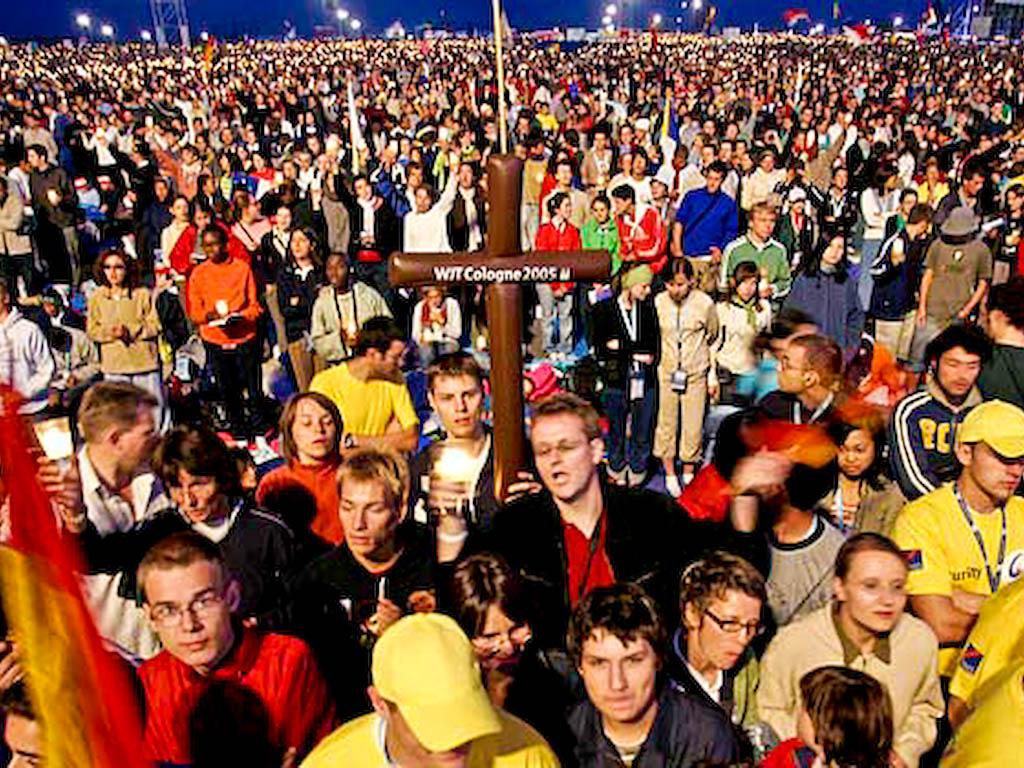

Vita Pastorale 17.07.2024 Enzo Bianchi Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgFinally, after a long time we are with expectation! Yes, the Church, as a human institution, must be reformed and purified. The current Synod is an action to reform the Church called for by the Holy Spirit through the word of God and the signs of the times. Will the Synod set this reform in motion? Francis wants it to and God's people hope so.

The Synod has set itself the goal of reforming the life of the Church and, therefore, it is necessary to reflect on this ever-present need in its history. The Church is a pilgrim towards the Kingdom, always to be reformed. Ecclesia semper reformanda: this may appear to be a formula of the ancient Church, but in reality, it is not found in the great debate of the Reformation of the 16th century nor in the preceding centuries. Karl Barth uses it in a 1947 lecture and later cites it in his Dogmatics as an attested adage in the life of the Church.

In truth, the Church has always felt the yearning for conversion in its members, for reform. But if, as Giuseppe Alberigo has observed, 'in the first millennium reform has an essentially individual and spiritual meaning, as an interior conversion', in the second millennium it has been invoked as a renewal of the Church, of its institutional form, as a return to the primitive forma ecclesiae.

In this sense, Jean-Jacques von Allmen read reformation as epiclesis (invocation) of Pentecost and parousia (final manifestation): 'A reformation is a provisional fulfilment of the prayer that the Church addresses to God to hasten the end, the coming of the Lord and his Kingdom. It is a prelude to resurrection, to judgement, to eternal life'.

Therefore, the reform of the Church is an act of obedience to the Spirit, to ‘what the Spirit says to the Church’: are not the seven letters to the seven Churches of the Apocalypse already an invitation to conversion and reform? And yet in Tertullian (The Veil of Virgins) we find another formula, which appears to be the opposite, and which was taken up by Blaise Pascal (Pensieri, 440): ‘Never shall the Church be reformed’, a formula that emphasises the strength of tradition, the continuity that does not foresee ruptures, the fidelity to the past.

It is certain that the word reform never enjoyed a good reputation in the Catholic Church after the great schism of the 16th century: reform was above all that initiated by Luther, 'the Protestant revolution'. Thus, the term reform appears as the title of a decisive book by Yves Congar, Vraie et fausse réforme dans l'Église (1950), and later recurs twice in the conciliar decree on the unity of the Church, Unitatis redintegratio (1964). There is such a distrust of the term that the official Latin text of Paul VI's encyclical Ecclesiam suam (1964) translates the Italian word riforma from the Pope's manuscript with the more neutral renovatio. Since Vatican II, the term riforma has been reintroduced into ecclesial debate, although it rarely appears in the texts of the papal magisterium. With Francis, however, it has become a frequently used term, indeed programmatic of his pontificate.

But what can the term reform mean? In Christianity, which is the reception of revelation, a canonical, rather exemplary, form is given: the forma Evangelii, the forma Jesu’s life, the forma ecclesiae. Reformation is action to restore to canonical form that has been obscured, wounded or even lost with the passage of time: it is action of conversion, of return. This movement must be incessant, ‘until the Lord comes’: precisely in anticipation of that day of the parousia, the Church, the bride, must make herself beautiful for her Bridegroom (cf. Rev 21:2), must reform herself to be according to the form in which the Bridegroom awaits her.

Therefore, the term reform, especially in the second millennium in the West, has had the meaning of a return to the lost or much contradicted primitive form. The Christian tradition has always looked to the summaries of the Acts of the Apostles, in which the Church born from Pentecost is presented as a description of the Church willed by the Lord and shaped by the Holy Spirit, thus as its canonical form at all times in history. The description of the primitive community, with the four notes or constancies, has always inspired Christian life. And at the beginning of monasticism, in the 4th century, monastic founders such as Pachomius and Basil refer to this form of Church. Of course, it must be reiterated that only the Lord Jesus can reform the Church, just as only God can give the gift of conversion: 'He who formed you will also be your reformer' (St Augustine).

The Church is responsible for listening, obeying, responding to the call, to the word of the Lord, to what the Spirit tells her. In the Decree on Ecumenism (UR) the Council dedicates paragraph 6 to the renovatio ecclesiae, clearly stating: 'Since every renewal of the Church (renovatio ecclesiae) consists essentially in increased fidelity to her vocation, it is undoubtedly the reason for the movement towards unity. The pilgrim Church on earth is called by Christ to this perennial reform (perennis reformatio) of which she, as a human and earthly institution, is in continual need'.

Unfortunately, there has been a long silence on this subject of the Church’s reform since Paul VI in the post-conciliar crisis during the pontificate of John Paul II, when a certain fear took hold of the hierarchy and, little by little, the language of restoration came back into vogue, replacing that of reform. In the encyclical Ut unum sint John Paul II attests to the link between renewal, conversion and reform, but this declaration is not followed by any beginning of the Church’s reform and the form of the papacy. And those are the years when those who call for the reform of the Church are viewed with suspicion, are marginalised and silenced in official ecclesial venues.

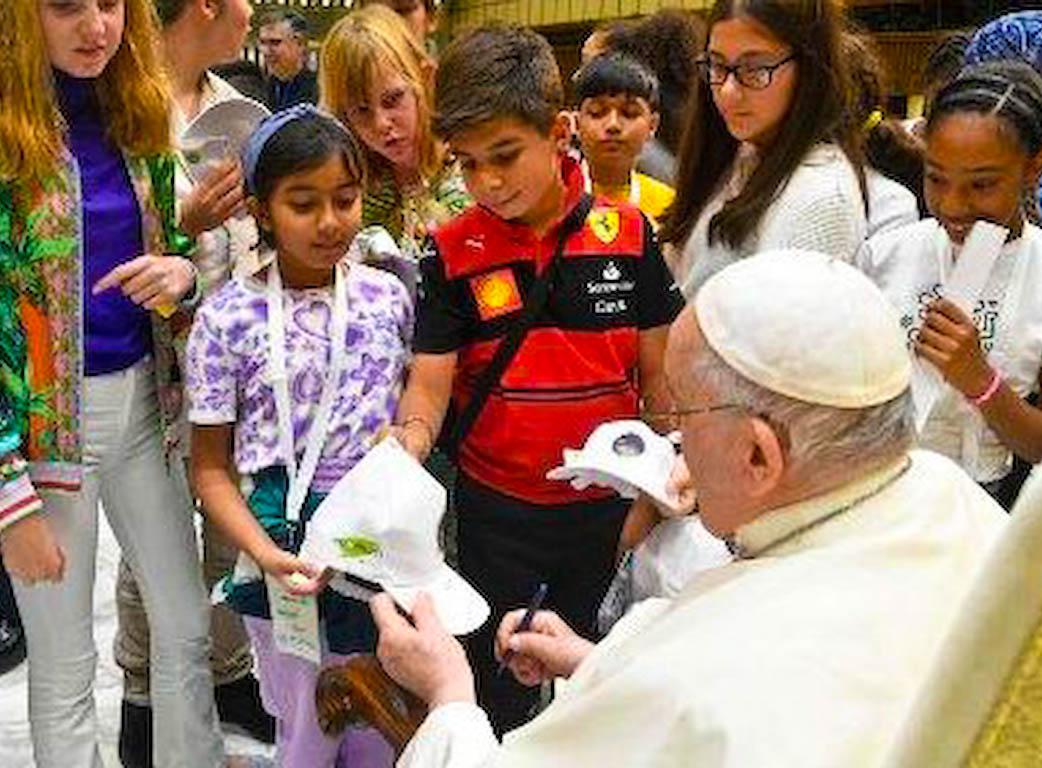

But here comes the unexpected: on 13 March 2013 Jorge Mario Bergoglio is elected Pope and immediately presents himself and is perceived as a reformer. He declares that 'what the Church needs most at this moment in history are the necessary reforms', combined with mercy.

He thus outlines the need for institutional reforms and reform of the Church's style. In Evangelii gaudium (2013), the programmatic text of his pontificate, he returns to the reform of the Church's structures and calls for a pastoral conversion, following the path traced by the Council. He speaks of conversion of the papacy (form of the Petrine ministry), of dioceses, of parishes. And, above all, he mentions the assumption of synodality as a necessary change in the Church's path.

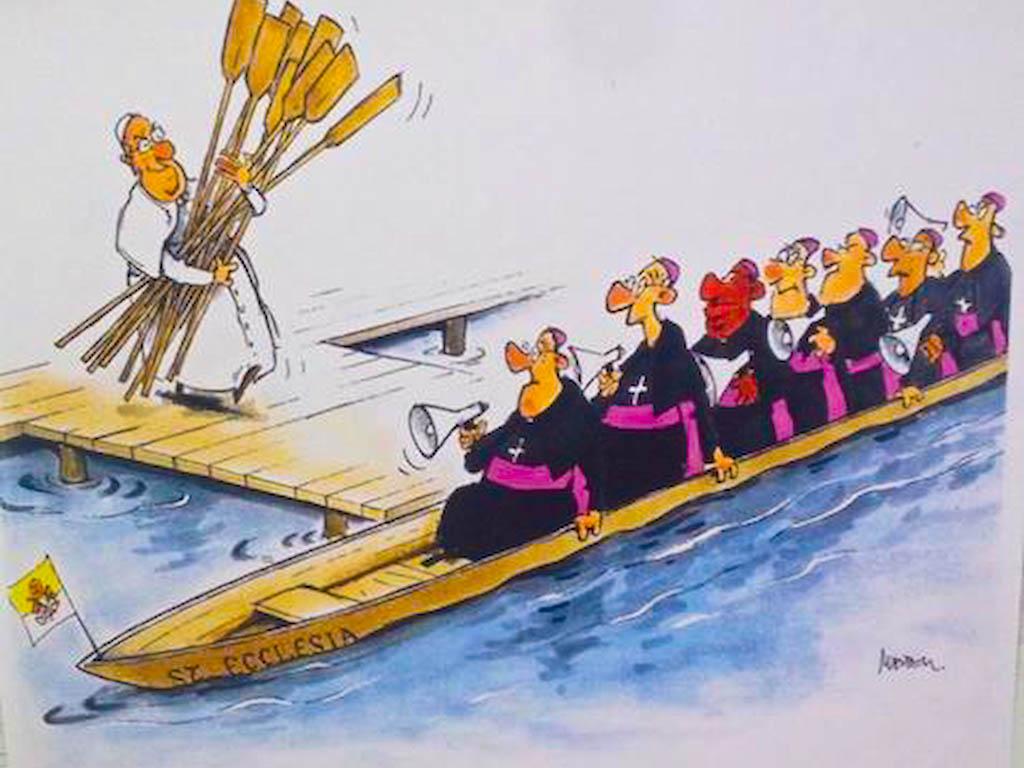

Francis has begun the reform of the Roman curia, he has changed the style of the papacy, he wants to implement a synodal style. Now, however, we ask ourselves: will the reform take concrete steps or will it remain just an announcement?

The reform of the curia should be called for what it is: reorganisation, not reform, which would require quite different changes and quite different understandings of the relationship between the ministry of Peter and the episcopate, between the Roman curia and the episcopates, of the episcopate itself present in the different peoples of humanity. Precisely because of this, in the ecumenical journey there are courageous gestures by the Pope and meetings between the Churches, in a renewed commitment to dialogue, but there seems to be no action to hasten visible communion. Today, ecumenism is either reform of the Churches or it is nothing more than cordiality between the Churches. And the reform of each Church is either also listening to the other sister Churches or it is not reform. If identity fears continue to prevail, the yearnings for reform will be extinguished. And no syn-odós, no walking together, will be possible.

Pope Francis, however, once again precedes and opens up new ecumenical paths. In fact, he wanted and approved the publication of a text that, taking up Ut unum sint, makes significant proposals to the Orthodox Churches on the Petrine ministry exercise reform and on synodality.

Finally, after so much silence, we remain in anxious and prayerful anticipation! Yes, the Church, as a human institution, must be reformed and purified. The current Synod is an action of reform of the Church called for by the Holy Spirit through the resounding word of God and the signs of the times. Will it be a Synod that sets reform in motion? Francis prophetically wants it to and hopes that God's people will follow him out of love and faithfulness to their Lord.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment