Being Church means having an idea of the future

Avvenire 25.04.2024 Francesco Cosentino Translated by: Jpic-jp.org"It is necessary to abandon all forms of nostalgia, focus on formation, become aware of the new times and overcome the postmodern logic of the provisional".

Questions keep the mind restless while answers risk putting us to sleep, especially when they are designed to anaesthetize the thinking fatigue before the complexity of today's challenges. Welcome, then, the debate that has been taking shape in recent weeks.

To Christian irrelevance, understood not so much in a sociological sense but as the inability of Christian symbols and words to touch the imagination, pierce the heart and mark the lives of our recipients, I recently dedicated a theology text published by St Paul's, believing that the question already posed by Karl Rahner a few decades ago should be placed at the center of theological reflection and pastoral action: how is it possible to experience the God of Jesus Christ today in a society that has marginalized him? This is a question that Christianity must begin to ask itself.

There is little point, in fact, in continuing to linger on analyses concerning the epoch change, Christianity’s end, the demise of sociological Christianity and the secularism advance, if we do not summon up the courage to take a further step, which can be stated as follows: if Western culture is no longer hospitable to the Christian proclamation, it is equally true that Christianity has long since ceased to be 'cultural', to be able not only to listen but also to interpret the challenges of the context, in a dialogue free from manias of moral superiority and of clericalism.

Christianity seems to be marked by a kind of 'culture of decline'. Recently, the president of the Italian Bishops' Conference, Cardinal Zuppi, spoke of this, saying: 'You cannot manage the present with a culture of decline, as if it were only a matter of pooling diminished forces, of reducing space and commitment, or of agonizing calls to combat.”

The culture of decline, which prevents us from having languages, proposals and posture to inhabit today's culture, manifests itself in many ways, and to mention some of them also means identifying those that can become places of restart, if we dedicate ourselves to them with passionate theological and pastoral reflection.

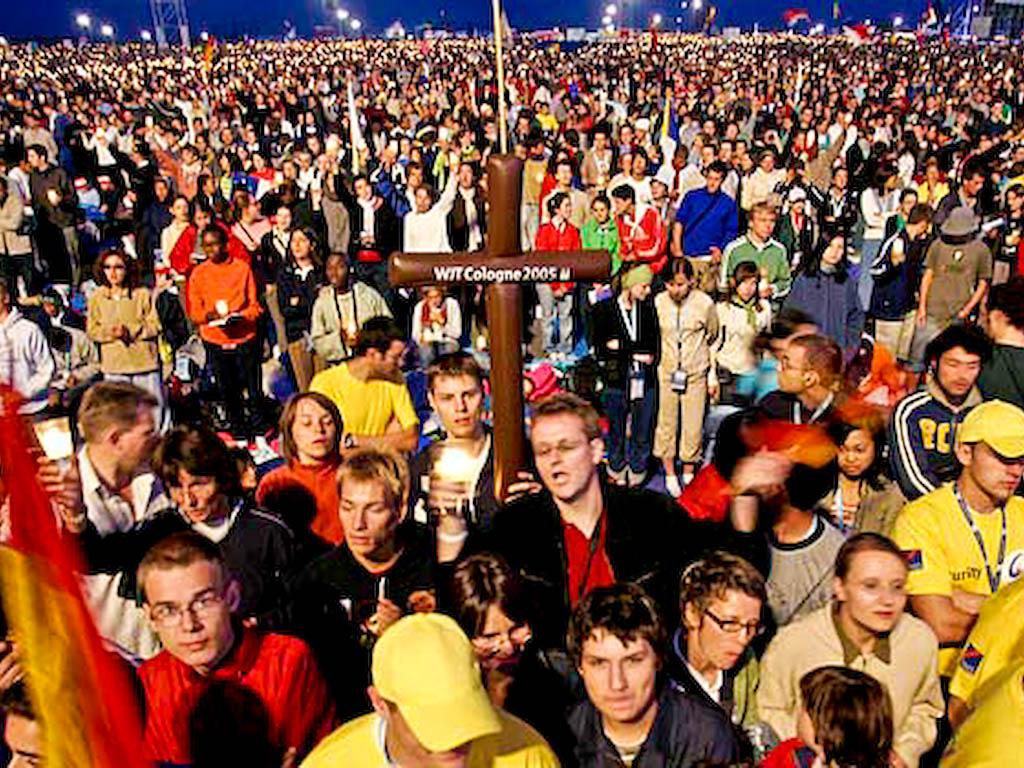

First of all, we must point out the risk of a victimized habit to the question of numbers, which often generates a hasty reaction, lacking a far-sighted ecclesial and pastoral vision: thus, we unite the few remaining forces or entrench ourselves behind a defensive attitude, limiting ourselves to preserving what exists. Perhaps what we need instead is the courage to take seriously the disproportion existing between the way we still think and the parish’s life and the dwindling number of priests and pastoral workers, in a context that has become mobile, plural, and multicultural.

Thus such a habit does not leave room and energy to think of a 'pastoral care of the threshold', centered on a proclamation of the Gospel that can intercept the distant and dialogue with the questions of our time and the cultural challenges, perhaps even stimulating debate among those who are in various ways engaged in the public spaces of the city, politics, and civil society.

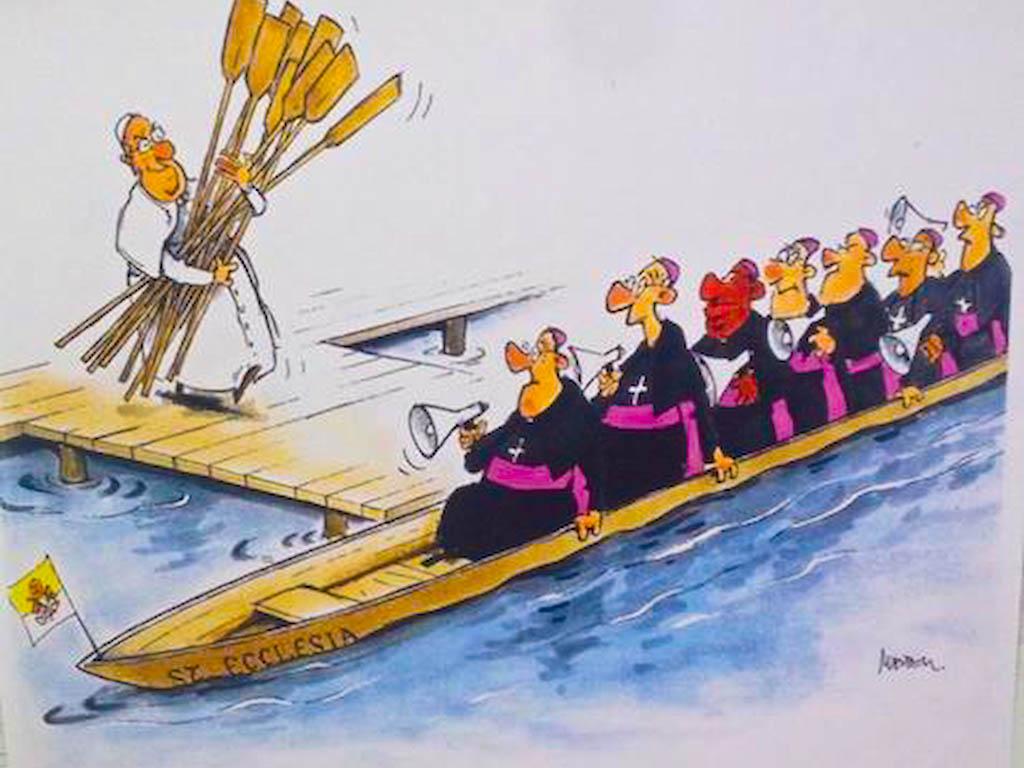

The issue naturally implies a reflection on ordained ministry, a new reading of the parish institution, some serious questions on the current juridical configuration and Canon Law, so as to imagine a new form and presence of the Church in dialogue with the territory. Instead, one has the impression that even with regard to the proposal, Christianity often proceeds with languages, formulas and practices that do not take into account how much the inner and conceptual imagery of our contemporaries has changed in recent decades.

One can continue to speak of salvation, happiness, human life, death and resurrection, but running the risk of no longer communicating anything if one does not take into account the anthropological changes, the diversity and plurality of meanings that each person gives to his or her own life experience, the post-modern search for a psycho-physical and spiritual well-being detached from the relationship with God, the 'faith' in artificial intelligence.

Shouldn't the words of the Christian event, one thinks, for example, of the profession of faith on the now close anniversary of Nicaea, be translated and offered again through a new linguistic-conceptual mediation? Finally, with respect to the culture and pastoral challenges, the impression is that even Christianity is proceeding in the postmodern groove of the provisional logic: it lacks a long-term vision and thinking, it goes on by hiccups and fragments.

In this sense, the ‘culture of decline’ is expressed in the retreat into intimist forms of religiosity and, even more often, into devotional forms that dispense with the effort of thinking and the burden of innovative and courageous choices. The scholar Sequeri has spoken of it such as a "retreat into the pure devotion of gestures and images vaguely connected to the Christian mystery", while the theologian Righetto has rightly referred to the spiritual "junk" found in religious bookshops, generating a sort of Catholic "subculture".

Certainly, there is an investment that is lacking, and if we speak of a dialogical relationship with culture, the main investment should be in education. While secularism has by now transformed the inner imagery of people's lives, changing the symbols through which they interpret life and inhabit the world, care for the formation and cultural, biblical and theological preparation of lay people and priests is still not taken on as an unavoidable commitment of a pastoral agenda.

A few days ago, the theologian Giuseppe Lorizio returned to the subject, affirming that the believer cannot ignore, and indeed must interpret and address a culture such as ours that shows itself in the guise of a 'polytheism' of knowledge and values, in a highly variegated and plurality of visions. Instead, it is considered more urgent to address today's needs than to invest for tomorrow. And on cultural formation, the old and ever new prejudice continues to weigh heavily, according to which studying and deepening are of no use, because it is enough to be close to people, say Mass and preside over a few acts of devotion.

The risk of the self-margination of Christianity becomes more than concrete, whether we take nostalgic refuge in the idealism of the good old days or close ourselves off in moralistic and devotional forms of Christianity. Something can change if and when we have the courage to put our hands - without fear and without ideological opposition - on a new ecclesial vision. But this will not happen by continuing to bet on a general pastoral vision, without the effort to think - and to think theologically - about the future of Christianity.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment