How a lone missionary found a way to defeat poverty

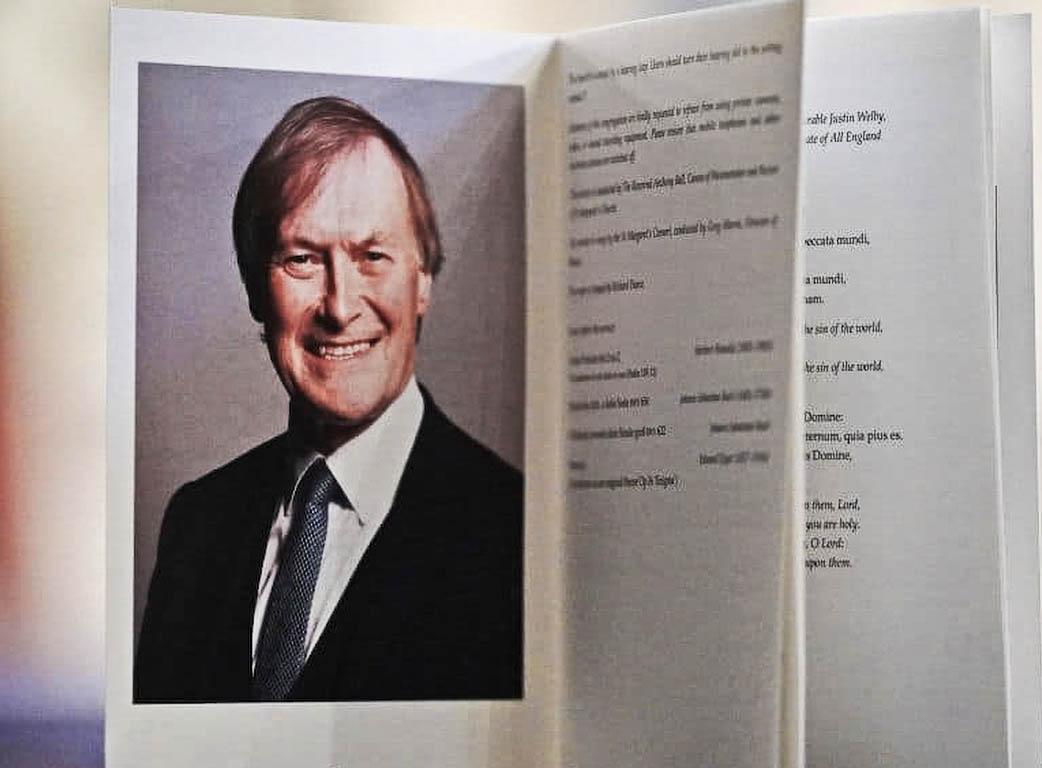

Catholic Herald 12.09.2019 Padre Raymond de Souza Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgPedro Pablo Opeka (born 1948), known also as Padre Pedro, is a Catholic Argentine priest of Slovene descent, working as a missionary in Madagascar. He exemplifies one of the new types of mission: not committed to converting, but fully dedicated to the poor, helping them to build their future. For his service to the poor, he was awarded the Legion of Honor. How did this happen?

When he visited Madagascar, the poor island-nation of some 26 million people in the Indian Ocean, Pope Francis made a visit to the Akamasoa City of Friendship, on September 8, 2019. Akamasoa is a community built upon a former garbage dump where people once foraged for food. Now there are nearly 30,000 people living in 5,000 locally built homes thanks to entrepreneurship and philanthropy organised by a missionary, Fr Pedro Opeka. Pope Francis remarked that the foundation “is a living faith translated into concrete actions capable of moving mountains” and that its success shows “that poverty is not inevitable!”

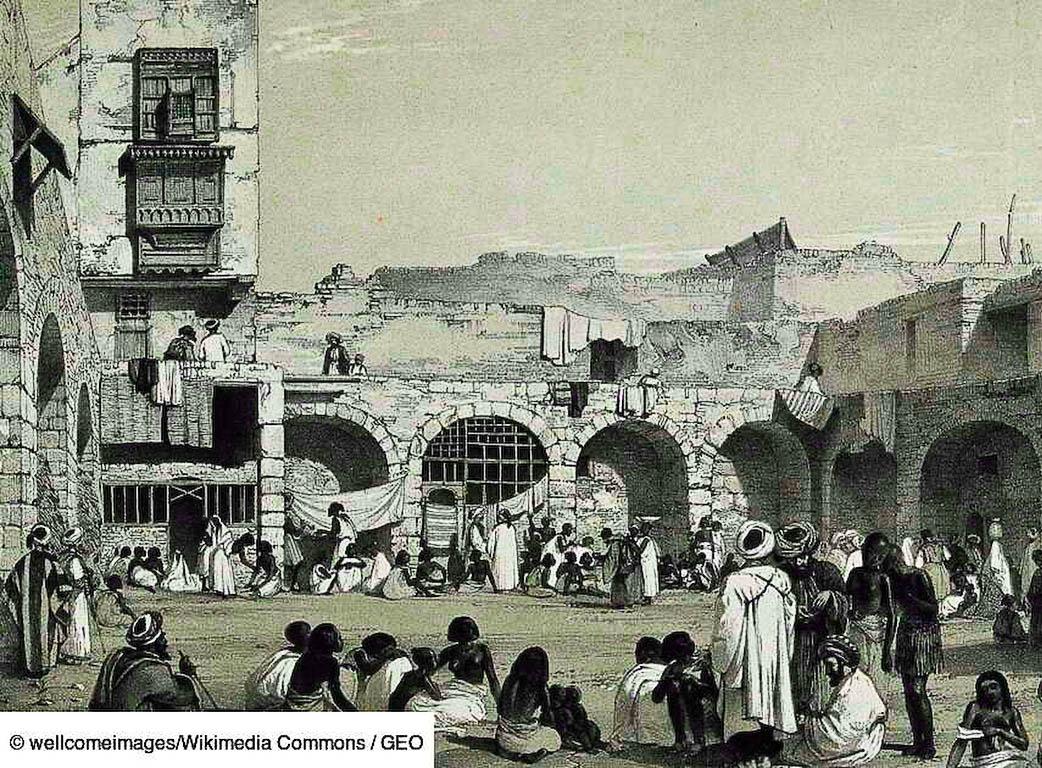

The declaration was remarkable and true, but it has only been accepted relatively recently. For most of human history, for most people, poverty was inevitable. Only recently, in the 17th-century, did mass populations achieve sustained economic growth; economic stagnation was the norm before that. Actually, economic stagnation only became a concept when there was an alternative, namely economic growth.

When Pope Francis was born in 1936, it was still widely thought that poverty was inevitable for the many, and prosperity was restricted only to a few. Widespread prosperity was for the northern nations or for the colonial powers, or the white race, or Protestants, or those countries rich in natural resources, or with large armed forces. No one thinks that way anymore; recent experience has shown that southern countries can grow, that Catholics can prosper, that countries without any natural resources can become very rich and that other races are no less creative and productive than whites when given the opportunity.

Pope Francis knows this from direct, inverse experience. He was a “bishop of the slums” when he was in Buenos Aires. He often visited the slum-dwellers and assigned priests full time to the slums, living among the poor they served. It is probably why he chose to visit Akamasoa.

From an economic point of view, there should be no slums in the great cities of Argentina. After all, there are no such slums in Canada. When Jorge Bergoglio was born Argentina and Canada were roughly comparable in prosperity. That is why Argentina attracted European immigrants like the Bergoglio family.

Why are there slums in Buenos Aires but not in Toronto? Because generations of bad political leadership and catastrophic economic policy made it so. Poverty is not inevitable, it follows bad economic policy. In Argentina and many other places, poverty is government-made.

Pope Francis said as much in Madagascar. He warned listeners against the social perils that he has denounced elsewhere – “corruption”, “speculation”, “exclusion” – and insisted that “development cannot be limited to organised structures of social assistance, but also demands the recognition of subjects of law called to share fully in building their future”.

“Subjects of law called to build their future”: it is an interesting formulation. It stresses that people need to be subjects of law in order to participate in the economy; arbitrary power and corrupt political structures make and keep people poor. Those subjects are to be exactly that – subjects of action, not passive objects. The poor would accomplish development of the poor, if they have the opportunities that “endemic corruption” and exploitation deny them.

Pope Francis expanded his vision to the environment itself – our “common home”. Knowing that “poaching, contraband and illegal exportation” threaten both the forests and animals of Madagascar, the Pope said, “for the peoples concerned, a number of activities harmful to the environment at present ensure their survival”; “It is important to create jobs and activities that generate income, while protecting the environment and helping people to emerge from poverty.”

The poor must have an economic interest in protecting the environment. The government mandates may appear fine on paper, but often they are circumvented by the corrupt – profiting the powerful and the rich, and serving to exploit the poor as they are forced into the underground economy where no protections exist.

People often misunderstand Pope Francis making him thinking that poverty exists until the government steps in to ameliorate it. The problem in Madagascar, or in Africa generally (and in Argentina, for that matter), is not a lack of government, it is bad government, officially denying subjects the rule of law under which they should exercise their creativity and productivity.

“We have eradicated extreme poverty in this place thanks to faith, work, school, mutual respect and discipline,” Fr Opeka said to the Pope. “Here, everyone works.”

Akamasoa works largely because Fr Opeka has managed to carve out a place where a functioning, benign, competent government works – namely, himself and the structures he has built over 30 years.

“We showed with Akamasoa that poverty is not fate, but was created by a lack of social sensitivity among political leaders who have turned their backs on the people who elected them,” Fr Opeka said. Not only in Madagascar.

On January 31st Father Pedro Opeka and his humanitarian association “Akamasoa” have been nominated for the Peace Nobel Prize by the Prime Minister of Slovenia, because Akamasoa Community has given an outstanding contribution to "social and human development" in Madagascar, helping it to achieve the 2030 UN goals for sustainable development. The Akamasoa Community has attracted public attention and support across the world because it is an inspiration in the fight against poverty, marginalization and social injustice.

In 1989, while director of a Vincentian theological seminary in Antananarivo, the capital of Madagascar, he noticed the extreme poverty in the slums of the city and discovered the human degradation of the “garbage people” scavenging the waste hills to find something to eat or to sell. He thus convinced a group of them to leave the slums and improve their lot by becoming farmers, teaching them masonry skills, which he had learned as a young boy from his father, so they could build their own homes. The idea was to give these people a house, a decent job and an education. Since then the project has grown by leaps and bounds, offering housing, work, education and health services to thousands of poor Malagasies with the support of many international donors and friends of the association.

See How a lone missionary found a way to defeat poverty and Father Opeka of "Akamasoa" nominated for Nobel Peace Prize

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment