Putin before Putism after

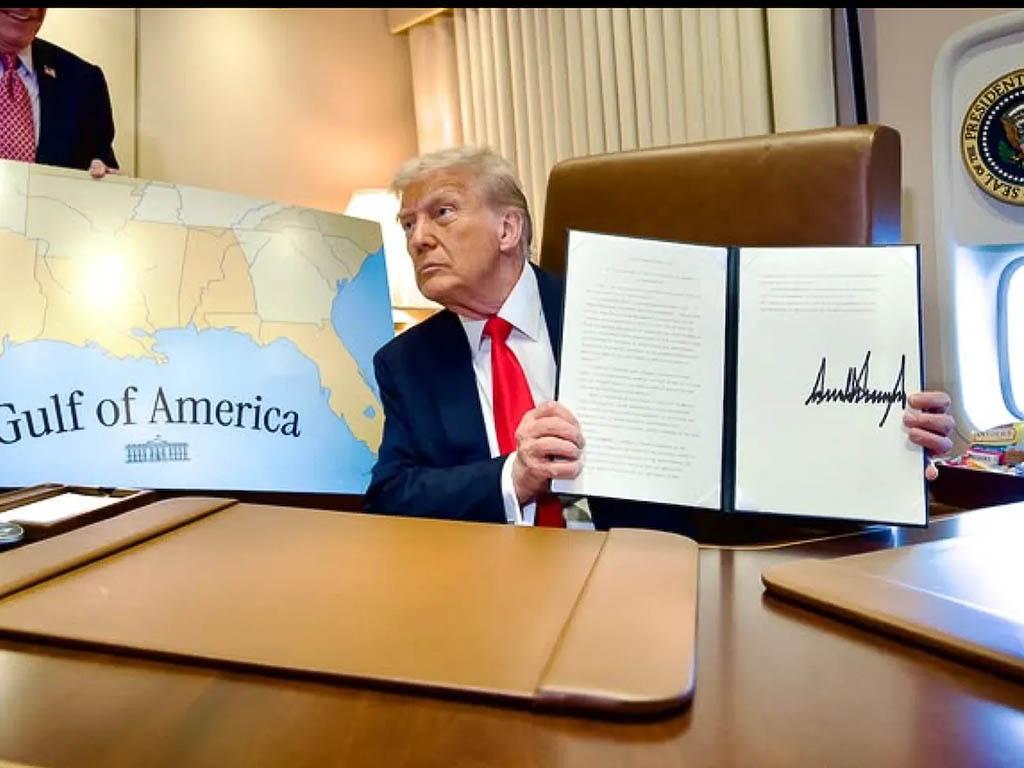

Ethic 07.05.2024 Ignacio Santa María Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgIn her latest book, ‘El imperio zombi’ (The Zombie Empire - Galaxia Gutenberg, 2024), Mira Milosevich, researcher at the Real Instituto Elcano and professor of International Relations at IE, delves into the causes that have led Russia to make aggression towards its neighbours and confrontation with the West the axes of its foreign policy. We talk to her about this and other tensions, aspirations and alliances that are currently roiling the world's geopolitical chessboard. Interview.

Two very bitter armed conflicts coincide in time: the war in Ukraine and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which has been complicated by Iran's attack on Israel. Is there any interconnection between the two?

They are two very different wars for different reasons, but they have three points in common. The first is that the US is sharing arms and intelligence with both Israel and Ukraine. The second is that Iran is arming Hamas, Hezbollah, the Houthis and different groups in Syria, Iraq and Pakistan that are attacking Israel. And the third common point, and perhaps the most important from a geopolitical point of view, is that both Iran and Russia are revisionist powers that seek to undermine the power of the United States as the leader of a bloc of liberal democracies. They perceive Washington as preventing them from becoming hegemonic powers in their own region.

Russia continues a race to reclaim former Soviet territories, while NATO is adding new members - Sweden, Finland and possibly Ukraine. Meanwhile, Poland is offering to host nuclear weapons. Are we heading towards a new cold war?

The Cold War, properly speaking, is one of containment, of deterrence, and today it could be applied to the relationship between the United States and China, which are the two great superpowers. Russia is no longer a great power, but a revisionist actor. In my opinion, a more apt expression would be Great Game 2.0. The Great Game is Kipling's term for the rivalry between the British Empire and the Tsarist Russian Empire in the 19th century in order to influence Central Asia, Afghanistan, India and the entire Middle East. To take this global view, I use the expression Great Game 2.0, which is a game involving many more territories, many more actors, and of course everything you have mentioned comes into it.

In The Zombie Empire you define as revisionist powers those that are not satisfied with the place they have been assigned in the current international order. Which countries fit that definition at the moment? Are they all a threat to other countries?

On the one hand, we have Russia, China or Iran, which I define as post-Eurasian empires, which justify their current ambitions with their imperial legacy, because they want to become hegemonic players in their regions and dominate their neighbours. But we also have countries like India or Turkey, to name but two that really believe they do not have the role they deserve in the international liberal order, but do not seek to dominate their neighbours. India rather wants to contain China. And Turkey (remember that the Ottoman Empire stretched across the Mediterranean) has no clear intention of being a hegemonic actor in the region. As for Russia, there is a point to be made: it does not have the economic resources to maintain what it was. It does not want to repeat the Soviet Union because it cannot, but it does want to maintain its influence. It wants to decide the foreign and security policy of the former Soviet republics, and that means trying to prevent them from joining NATO or the European Union.

One of the theses in your book is that, Putin or no Putin, Russia would have wanted to reissue that influential past and that this nationalist imperialist urge is stronger and deeper than ideological systems such as communism or autocracies such as Putin's.

In the 19th century, when nation-states began to be created in Europe, Russia failed in its attempts to create its own. The last chance came in the 1990s, when Yeltsin tried to turn an empire into a nation-state. This meant moving from a one-party to a multi-party political system, from a statist economy to a capitalist model, and from an imperialist identity to a normalised national identity. This was a Herculean task and it is not unusual for Yeltsin to fail. You cannot quickly change what has lasted four centuries. Russia built an empire by expanding and now maintains with the former Soviet republics - which were also part of the Tsarist Empire - a historical, linguistic, religious, traditional link... For example, Russian is still the official language of doing business, even in the Baltic countries, which hate Russia, but where everyone speaks Russian. It is easier to try to exert post-imperial influence there, because there are very strong links that are still there.

If we understand Putinism as this kind of revisionist nationalism with imperialist zeal, will it continue to exist once Putin disappears biologically or politically from the scene?

The main thesis of my book is that trying to explain everything that happens in Russia with the figure of Putin is a simplistic approach that does not work. For example, Lukashenko is a Putin-style dictator, but he is not trying to conquer former Soviet republics. There is an imperial legacy there that cannot be explained just because there is a person like Putin. So I think there will be Putinism after Putin, and it may be even more nationalist and more radical, as we have seen in figures like Yevgeny Prigozhin.

So does democracy stand a chance in Russia?

Democracies have mechanisms to change governments, regimes do not. Regime change only comes through a military coup d'état or a revolution. A revolution is possible, but I don't see it as likely now because Russians have had two during the last century and are very tired of such radical changes. Besides, Putin has a lot of support. So I see more Putinism in Russia in the future, more radical or softer. Softer in the sense that he might be succeeded by a technocrat like (Mikhail) Mishustin, who is the prime minister. But we don't know that. Putin has so far given no hint of what might happen, nor has he named a successor. He is in good health, although there is a lot of talk to the contrary. So I don't think there can be a quick change.

China is an actor that, on the one hand, supports Russia in UN votes and helps spread Putin's discourse, but on the other hand, has a very different roadmap, which is to become the world's leading power by around 2050 through trade. It's a different style of expansionism.

Yes, it's a completely different style. And the new cold war between the United States and China is going to be quite different from that of the last century. China does not use conventional military force, on the contrary, it shies away from it. Its best asset is strategic patience, but it has very clear long-term goals. The new cold war would be fought in the field of technology because that is the most important factor in the contemporary economy. Look at how Washington has banned US companies from collaborating with Chinese companies: it has really marked out the territory of this new cold war battle. The United States, in terms of power, is still the power that invests the most money in the military industry and contributes the most to the world's GDP... And yet it is losing influence. Power and influence are not always the same thing. What China, Russia, Iran and India agree on is that they are committed to a multipolar world order.

And in this new world order to which we are heading, is Europe clear about its role or where it wants to go?

In R&D (Research and development), Europe does not have the capacity to compete with American or Chinese companies. It has reduced its dependence on Russian energy, but has increased its technological dependence on China and on US liquefied gas. Much has been said that Europe has had two alarm bells: one was the pandemic and the other the war in Ukraine. But it is one thing to wake up and another to have the strength to get up. Europe is aware that, at the moment, it does not meet any of the criteria for the stability of an empire-state: demographics, energy, military spending and a competitive economy. And it is not only Europe's fault: the US has passed laws that subsidise domestic industry, protectionist measures. The transatlantic alliance remains political and military, but economically the US has become a competitor. A lot of work needs to be done to raise awareness that if the transatlantic alliance is very beneficial for Europe for many reasons, it is also for the US. The US is wrong if it really wants to go down the road of becoming Europe's rival, even if only economically.

See, «Explicar con la figura de Putin todo lo que ocurre en Rusia es un simplismo que no funciona»

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment