Sacred and profane love

La Stampa 14.07.2024 Vito Mancuso Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgThe separation between sacred and profane love at this point disappears, because when you go deep down, love is always and only sacred.

In this age of chatter, noise and consequent confusion, the task of thinking is to introduce clarity, rigour and cleanliness into the mind, and from there into the heart. For this reason, when speaking of love, I begin by giving a definition: ‘irresistible attraction that provokes in the subject a permanent change of state’.

Love is not a simple attraction, in order to have it in its authenticity the attraction must be ‘irresistible’; otherwise, you only have interest, sympathy, inclination, affection, transport, but not love. It is about the difference between saying ‘I like you’ and saying ‘I love you’: we can say ‘I like you’ to many people, while ‘I love you’ to only a few, very few in fact, perhaps just one. And it is certainly no coincidence that while everyone can say ‘I like you’, not everyone knows and can say ‘I love you’.

Of course, this is true as long as one uses words with the right weight, because where this is not the case, one can say anything, for example ‘oh how I love you’ to someone who gives us a lift, or call ‘love’ to every person or small dog one meets. This use of words causes them to lose their value according to that process in economics known as inflation, which designates the loss of the purchasing power of money; well, there is a loss of purchasing power of words too, because if we use ‘love’ so casually, what will we one day call the person who will be unique and who, if he or she were no longer there, would cause an unbridgeable void in us?

Love, then, is an irresistible attraction. In order to be truly such, differentiating it from falling in love of which it is, so to speak, an upgrade, it must produce in the subject experiencing it a ‘permanent’ change of state. This is the same change that occurs in the oxygen atom when it associates with two hydrogen atoms generating the water molecule: in the same way, the couple is no longer two atoms, but becomes a molecule. From chemistry to physics: today in quantum physics we speak of a quantum leap to designate a sudden change of state or energy levels; well, love, to be such, must generate a quantum leap, a passage of state.

‘Incipit vita nova’, wrote Dante at the beginning of his work of the same name to celebrate his new existence enlightened by his love for Beatrice, a real woman and at the same time an allegory of philosophy (conducted in the light of theology) and at the same time of theology (conducted in the light of philosophy). Even between philosophy and theology, in fact, there is a symbiosis that produces a new spiritual molecule: its name in ancient Greek is ‘Sophía’ [wisdom].

This change of state from a single atom to a spiritual molecule generated by love is mirrored by the language that designates the two members of the couple with names such as ‘spouse’ (from cum + iungo, I unite with), ‘consort’ (I share my sort with), ‘companion’ (cum + panis, I eat my bread with). If it is therefore true that love destabilises because it presents itself as a sudden and sometimes even unwanted change of state; it is even more true that it then stabilises at a higher level, it becomes a source of solidity, strength, fortress, rock, refuge, the safest from the storms of life.

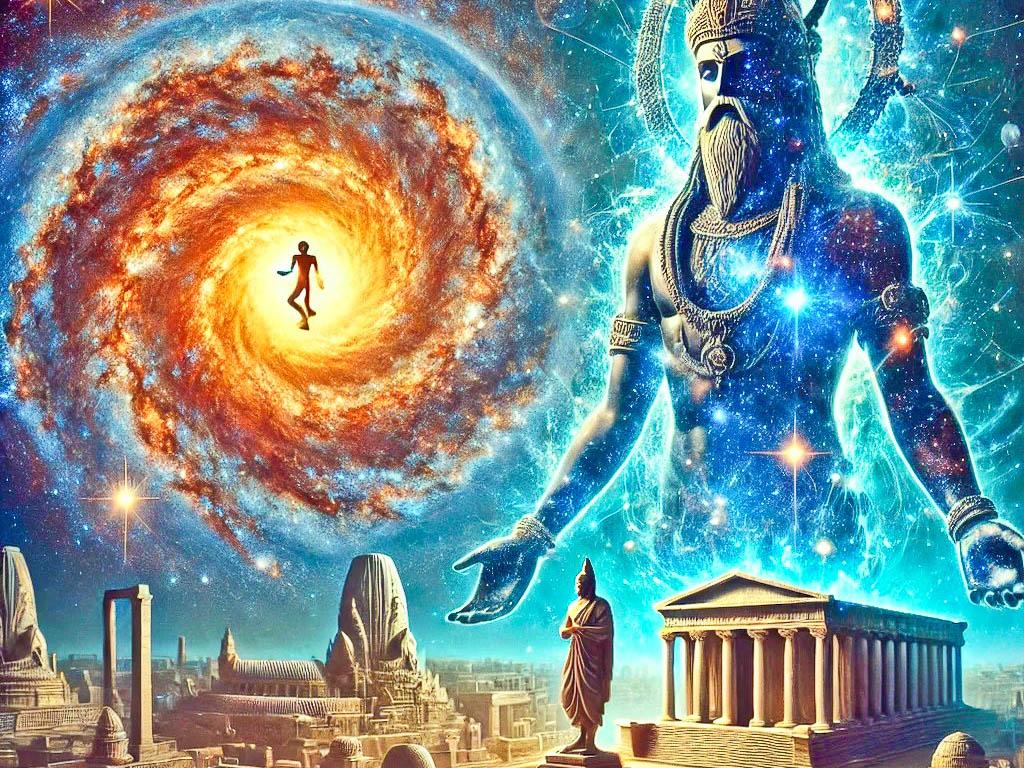

There is also a love for God. When a scribe asked Jesus which was the first of the commandments, he replied: ‘The first is: Listen, Israel! The Lord our God is the only Lord; you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul, with all your mind and with all your strength'. But what does it mean, exactly, to love God? What does one love when one says one loves God?

In the life of a human being, love for God manifests itself initially as attachment to one's religion with its symbols, its doctrines, its liturgies, its representatives. So, one says ‘I love God’ and in reality, he loves the Church, the Bible, the Pope, the doctrines and dogmas of the catechism, producing this frequent short-circuit: God - Religion - Church. Spinoza noted it to perfection in 1670: ‘For the vulgar religion means paying the highest honour to the clergy’.

The more one progresses in spiritual maturity, however, the more one realises how divinity is far beyond the teachings and rituals conveyed by religions. This is what the experience of the mystics teaches. Gregory of Nyssa, the 4th century Church father, writes: ‘There is divinity, where understanding does not reach’. That is, as long as there is understanding, there can be no authentic experience of God. Augustine a century later says the same thing: ‘If you have understood it, it is not God’. All the more reason, however, to ask what it means to love God: how can I love what I do not understand?

Augustine posed the question by addressing himself directly to God: ‘What do I really love when I love you?’

In his answer, he names neither the Church, nor the Bible, nor Jesus, he rather proceeds by denying a series of beautiful things as the object of his love for God: ‘Not the beauty of the body nor the grace of age, not the radiance of light nor the sweet melodies of songs, not the fragrance of flowers, ointments, aromas nor the manna and honey, not the limbs made for carnal amplexus: this is not what I love when I love my God’. And then he continues: ‘Yet in loving my God I love a certain light and a certain voice and a certain perfume and a certain food and a certain embrace’. And he specifies: ‘The light, the voice, the perfume, the food and the embrace of the inner man within me’.

Here's the point: by loving God, we love the light of our interiority. That is, the promise of meaning, of beauty, of justice, of goodness, contained deeply in our conscience and in which our conscience ultimately consists.

It thus appears that between love of God and love of self, there is no opposition; rather, by loving God we love the light of the inner man within us.

Many centuries after Augustine, reasoning on human love, the young Hegel wrote at the age of 28: ‘Love can only take place in standing before our equal, before the mirror and before the echo of our essence’. This is exactly the same dynamic that Augustine captured with regard to love for God! I love God and I love the light of the inner man within me. I love her (or him) and I love the light of the inner man within me.

Supreme egoism? No, because if I love, I go outside myself, there is a change of state: but this change is actually fulfilment. We are fulfilled when we unite with our half by recreating the original person, according to Plato's myth recounted in the Symposium; and we are fulfilled when we unite with the promise of meaning, beauty, justice and love conveyed by the concept of God.

The separation between sacred and profane love at this point disappears, because when we go deep down, love is always and only sacred.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment