A Church with open doors and windows

https://www.alzogliocchiversoilcielo.com/ 21.12.2022 Daniele Rocchetti Translated by: Jpic-jp.orgAndrea Grillo is a theologian, professor of Theology of the Sacraments and Philosophy of Religion in Rome and of Liturgy in Padua. It is interesting to resume this interview at the close of the 1st session of the current Synod. Interview by Daniele Rocchetti

Will the Synod put forward the question of power and its dynamics?

This is one of the clearest ideas that are emerging in current Church events and in the cultural debate beyond the Church, in what we can call common culture. We have to react to a sort of self-defence instinct proper to the Church. When the Church hears about power, it says 'it does not concern me, because I move in the region of service'. False: the exercise of true authority, the authority of the Gospel, the authority of service, exercises power. To lose it perhaps, but it must be exercised. Now, in the exercise of power one touches upon a whole set of mediations that are common, not specific only to the Church. A reflection on these mediations is important therefore.

The language is the first mediation in which power is exercised. The Church speaks an old language, which was young when it was formulated. It was modern, bold at the time of St. Thomas, the Council of Trent, and the 19th century Councils. Today we repeat tired formulas. We must not be afraid to recognize it. On this Pope Francis is very frank and asks us to use imagination, restlessness and incompleteness. It is no coincidence that he uses these three surprising words. And it is paradoxical that a Pope says them and not theologians, pastors, lay people. We must say the things of always with new words. This is the great insight of John XXIII, who opened the Second Vatican Council by claiming that it had a pastoral character. Because, said the Pope, one thing is the doctrine substance, the depositum fidei, and another is its formulation, its covering. We must formulate the covering of the ancient tradition in a new, surprising, exciting way. And exercise power by using language in a new way.

And the second thing?

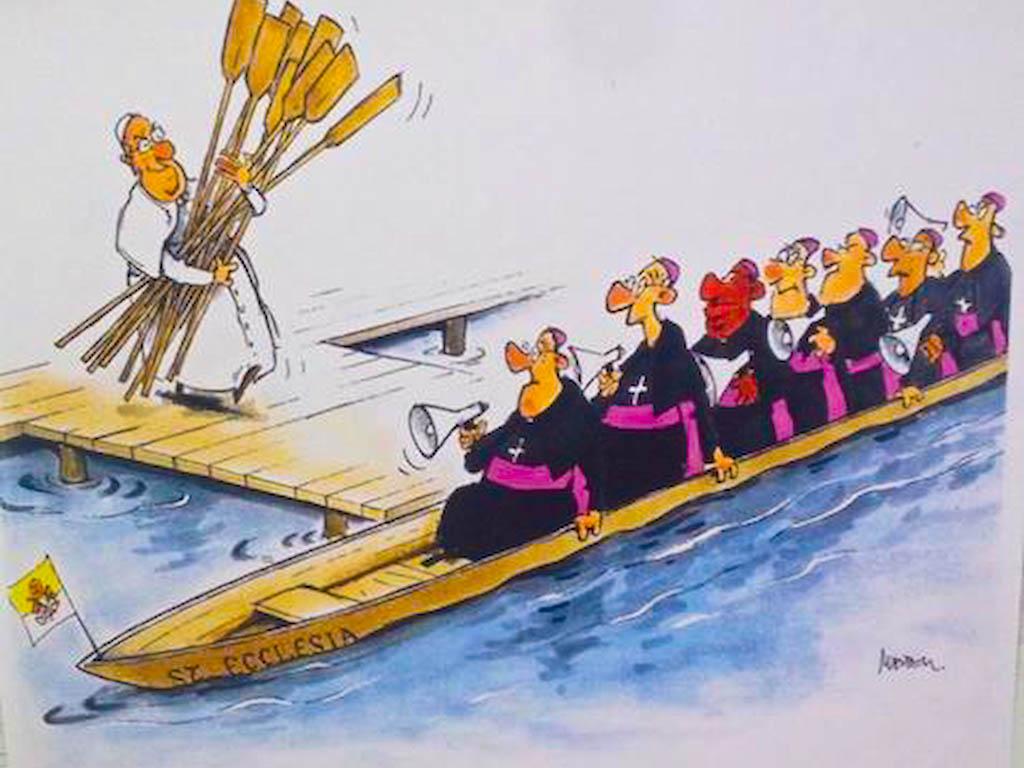

The Church must get out of self-referentiality, which is normally a consequence of old languages. Languages are old when they only talk to themselves. In the Church this is one of the temptations of all time, that of a Church that is no more able of 'going out'. Bergoglio used the image even before he became pope. It is not the 'Church’s going out' but of Jesus going out: we must allow Christ to go out of the walls we have built around him. It is a beautiful image: a 'Christ going out' that needs a Church with open doors and windows, letting Him out and the lives of humans in.

And the third level?

It is strictly institutional. Canon law - conceived in 1917 and partly reworked in 1983 - is used as if it were the Bible. Let's stop reducing everything to canonical matters. Canon law has an essential function, but it is neither at the beginning nor at the end. It is in the middle, at the beginning and at the end there are other things. A Church with canon law always at the beginning and at the end is a Church that speaks a self-referential language, that does not communicate with reality. Everything becomes easier and more realistic if we finally let the sign of the times - that John XXIII spoke about in his last encyclical Pacem in Terris - enter the Church: women. Even before the synodal work began, Pope Francis made important choices on this matter in 2021.

The delay of theologians, pastors and lay people. What are the reasons?

They are many and come from afar and from near.

From afar. At a certain point in the history, for reasons understandable then, certainly not today, the fear of the modern world made the Church cling to its acquired culture. It was as if it no longer needed to read reality and had all the answers even to questions not yet asked. It was the end of the 19th century, early 20th century, the time of anti-modernism. We are still today, after more than a century, children of that season.

Pope Francis came to wake us up because we were convinced that we were fine where we were, that is, inside our world. We thought we did not need to go out.

Take priests. Priests and theologians are only formed with self-referential speeches. The Tridentine seminary was born as a place of culture. Instead, the seminary of the late 19th and early 20th century became a place where only sacred subjects were studied. Literature - and we are not talking about the sciences - the less is done the better. Italian seminaries until the end of the 19th century, were also full of scientists. Since then, very few priests study scientific subjects in an advanced way, to do research, which gives rise to suspicion towards all that is modern science.

Then there are the proximate causes. After the Council, which is the great thaw from anti-modernism, a kind of new anti-modernism emerges in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s. The Church says big no's: no to interventions on ecclesiology, ministry, liturgy. Everything is blocked because everything has already been decided in the past. Pope Francis comes from South America, another world compared to Europe. The first pope who is a non-conciliar father. He feels the responsibility of one who is a Council’s child: he shakes up theologians and pastors who continue to think of fidelity in terms of immobility. Francis has had civil and religious experiences that have allowed him to break out of this somewhat caricatured self-representation of the pope, the bishop, the theologian, the pastor and even the layman. He ends up against a European and Italian mentality that is instead convinced that to be Catholic Church means to repeat the previous century Church.

The distinction between tradition and traditionalism is therefore one of the hubs around which some Catholics are building barricades today.

Tradition has always been there. Traditionalism is a product of late modernity. Tradition is a human, institutional and ecclesial mechanism by which the new is guaranteed to be in relation to the past: it is the guarantee that new things can happen that are assimilated gradually, from generation to generation, allowing the past to make room for the new.

Traditionalism is one of many -isms, the attempt to enclose tradition in a museum, instead of making it flourish like a garden. One wants to keep it always the same even if it is dead. Traditionalism makes the Eucharist, the bishop, the parish into museum objects. One thinks of guaranteeing them by keeping them always the same, always the same.

The prayers are always the same, nobody learns a new language, everybody speaks only Latin, and everything is dead. It is said that Latin guarantees the universality of the Church: yes, but for whom? Latin, if it is a language, must be understood, in order to be able to agree with. Even things are written for everyone in Latin, everyone then understands them in their own language: one in English, the other in French, the other in Italian and the other in German. The Council understood this sixty years ago: "let us play universality over particular languages", not a language that has not been alive since Dante declared that to make poetry, to speak about life, one had to use the vernacular. That was in the 1300s. The Church took a few centuries longer to understand it. The Protestant Church got there in the 1500s, the Catholic Church in the 1900s. You can use Latin for canonical documents, but the experience of faith is no longer done in Latin. Traditionalism sees Latin as an untouchable language to guard the faith: it is one of many examples.

What are the expectations regarding the Synod?

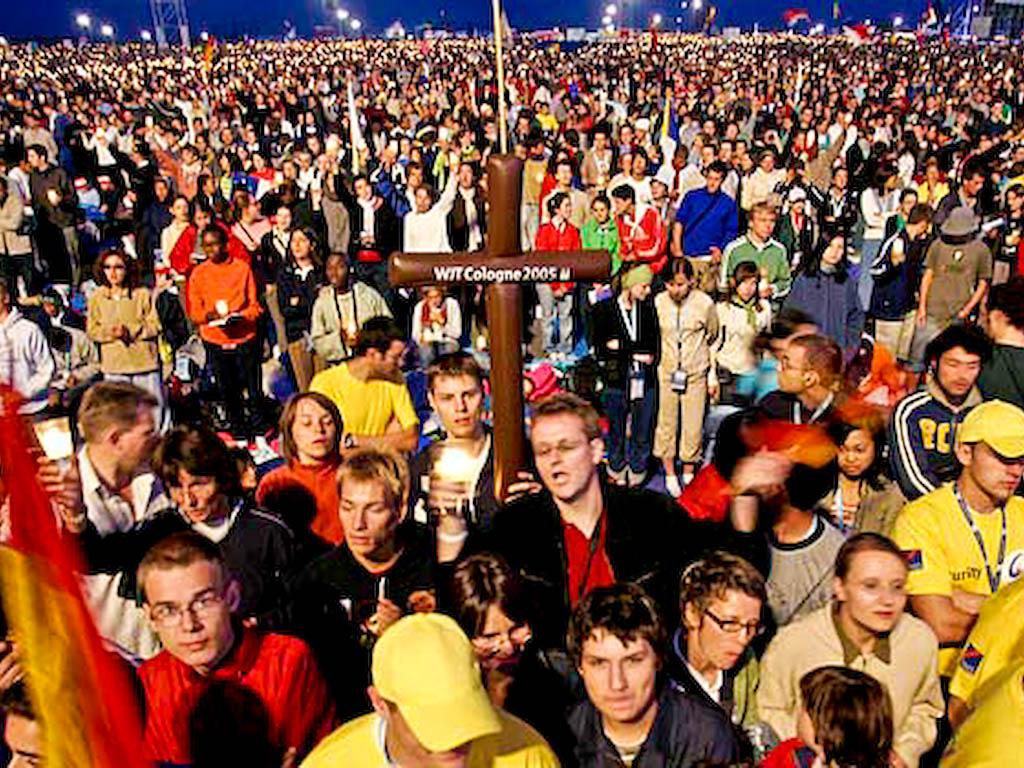

They are good if the Synod is an opportunity to listen. A Church that listens is a Church that accepts the logic of the signs of the times. An important word: the signs of the times. It means that in history things happen from which the Church has to learn.

Does it mean that in history, there are things that deserve attention? No! For Pope John - in 1963! - the signs of the times were something different. They were peoples having the same dignity, workers having the same dignity as employers, women having the same dignity as men. The world has moved on and there are now other signs of the times to be read: they are the issues concerning nature, Creation, new forms of experience of feeling, of relationships. In short, there are worlds that are changing and in which it is possible to find elements of evil and good and then learn to discern.

Does this mean, a serious confrontation at last with modernity?

The two Synods that have been launched - both the universal one and the one proper to the individual dioceses - have the opportunity to get in tune with this need to listen. The signs of the times must be processed. The need, therefore, to work on language, institutional reforms and the rights-duties-gifts of the subjects. These are the three fronts on which to emerge from the ancien regime forms that still run the Church. Sometimes we do not realise that we confuse the ecclesial tradition with the Tridentine or nineteenth-century forms with which marriage, parishes, and relations with states were managed. They were good solutions in times past, but today they hold water. It is hard to see why we should still keep them, except by confusing the normativity of God's word and tradition with the normativity of history individual step.

There are things in tradition that are good to die so that the tradition continues. It has always been like this; it is not as we were inventing it today.

Take the priesthood. In the history of the Church for a long time there were no seminaries. It was the Council of Trent that imposed them. At first it was a trauma because there were those who said, 'It was never done this way, it was always done differently'. The Council of Trent had the courage and authority to say: 'No, future priests must go to seminary'. Today, this solution no longer works. Perhaps today one should not have to do the seminary to become a priest. We know about Ambrose, but also Augustine. They became priests by force, they caught them, threw them into the Church and ordained them. A violent way that we would not accept today, but, in history, there has also been a Church like that. So, we should not be shocked if the seminary is reformed, if the jurisdictions of the dioceses, the canonical courts are reformed... These are all things that pass, their historical forms are not definitive.

What does it mean for the Church to take the synodal form? That is a configuration, a posture that is at least unusual for the Western Church.

I think it means taking on the good that is within the experiences the Church has had in the past and in the present. Coming to terms, discerning what has been brought about by the revolutions that have changed the world. I am thinking of the industrial revolution and the liberal, French and American revolutions. Beware of a misunderstanding we can slip into when using the word Synod. The Synod of which the Tridentine Fathers speak about and those that were celebrated only among priests in two days in the 1950s have little to teach us. The Synod we are talking about today is the classic form but rethought with new categories: how freedom is exercised, who votes, what topics to talk about.

There were immediately bishops who said 'No, this is not to be talked about'. In reality, if it is a Synod, no one first establishes what is to be talked about. On this, Pope Francis has been very clear from the beginning. Synodal Church means a Church that allows itself to be taught by the worlds of democracy, always unfinished, but in which one listens. A Church that is taught by new styles of dealing with reality, of listening to the Gospel and being close to those who need the Gospel’s word most. A Church capable of putting itself in a synodal posture becomes a place where one needs the other to be oneself, taking leave of a Church’s model holding an authority in competition with that of the State or Universities. An imaginary of which we are still victims, for which neither the Middle Ages nor the Council of Trent but the 19th century is responsible.

A change of no small significance...

Certainly. Through the synodal style, we learn the art of being Church without resorting to forms of exercising power. And without depending on forms of identity and relationships typical of the ancien régime. Unfortunately, the Catholic Church is often still identified with non-democracy, with non-consensus. So often we hear: 'The Synod is not a parliament'. Yes, but we must learn something from parliament: consensus is fundamental, not to make decisions in an absolute sense, but to understand how things are. Only in confrontation can one truly understand what it means to love today. And also, what it means today to live together, what it means today to work together.

Let’s try to understand. The Church is not a democracy, but it cannot avoid listening and confrontation. How can these two instances be brought together?

This is about working on institutions. The temptation that we experience today, both in the Church and outside the Church, is to think that by making new laws things will be OK. Laws alone do not change mentalities, ways of living and doing. However, it is also true that if synodal instruments, confrontations and listening only serve to mature consciences, it does not take into account that people also react to institutional acts, that is, to permits, prohibitions, guidelines, incentives. The Church must take note of this. If we discuss, talk, but do not take concrete measures of openness on the ministry level, if we do not adopt forms of consultation of the sensus fidei other than optionality, we run the risk of not making any impact.

The canonical codes are basically sweeteners of an absolutely monocratic system, incapable of managing the division of power, whereas in the Church some experiences of power division are necessary. It is not that there are none, but they are mainly ad intra. Ad extra, the Church is absolutely monolithic. This is a limitation, because it speaks a language that is two hundred years old. The balancing point is to accept that the fundamental norms of the Church's life have something to learn from the life development and institutional forms of modern men and women.

Try to see, for example, how one handles the case of crimes committed by churchmen, whether priests or laymen. What is needed today is a transparent dialogue with civil justice. But the rules do not allow us this, because we have built legal and institutional worlds that are opposed to those of the state. This no longer holds. And it also applies to what has to do with marriage, forms of penance and much more. At first sight, this seems aberrant, but it has always been so: the changes have always been of radical confrontation with the world.

Will the Synod succeed in giving voice and listening to those who live on the margins of ecclesial affairs?

I believe it can, I have hope that it will, provided we accept to convert. I am not just talking about the heart’s conversion, which is fundamental. But also, of converting the mediations of the heart, that is, our way of speaking, of thinking, of constructing ecclesial experiences. It is easy to speak in biblical words. It is more difficult to translate them into the present, because we are still bound to the meaning horizons of a hundred, a hundred and fifty years ago.

For example, the word homosexual, many Christians immediately associate it with a sin against chastity. If one reasons in this way, one is handicapped in relation to reality, because one sees sin first and not the person. In this case, but I could make many others, the categories with which one thinks are old and they no longer work. To be homosexual is not first and foremost - even if it may seem so to someone - to sin against chastity. This idea is the fruit of a world and a history that we have behind us but which no longer holds today and which marginalises, leaves out.

EDitt | Web Agency

EDitt | Web Agency

Leave a comment